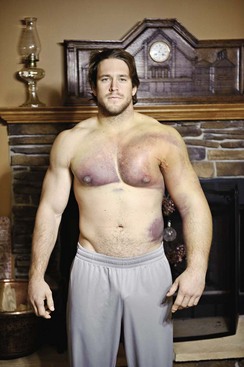

Chapter 35 Since the first described report of a pectoralis major muscle rupture in 1822, our understanding of the injury has evolved. Previously, pectoralis major tears were recognized as rare injuries incurred by manual laborers who could tolerate functionally negligible strength losses. Before the year 2000, the number of cases reported in the literature was below 150; however, since the year 2000, over 220 additional cases have been reported. This coincides with the increase in the number of individuals pursuing athletic endeavors, as well as those pushing the limits of human performance in training for such sports.1–3 These athletes cannot continue their sport at the same level without maximal clinical outcome, which is most reliably obtained by surgical repair. Pectoralis major muscle injuries have been, are, and will remain a traditional topic of orthopedics in which our understanding of anatomy lays the groundwork for a thorough history coupled with a complete physical examination to reach the diagnosis. We are able to apply advancing surgical methods to provide our patients with the best possible outcome based on the needs of the individual. Men in the third and fourth decades of life are those primarily affected by pectoralis major muscle injuries.1,4 Most commonly, tears occur as complete distal tears at or near the insertion on the humerus but can also occur at the musculotendinous junction.1,4–6 Tears generally involve the sternal head but can also involve both heads or the clavicular head alone.3 The pectoralis major muscle is responsible for adduction and internal rotation and contributes to forward flexion. It originates broadly from the clavicle, the sternum, the ribs (first through sixth), and the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle; however, it inserts in a more focal manner on the anterior aspect of the proximal humerus.7,8 The pectoralis major is a unique muscle capable of maximal power production over a broad range of velocities of muscle shortening. It is composed of a larger sternal head and a smaller clavicular head; the sternal head has a bilaminar insertion of three segments anteriorly and three segments posteriorly.7 Within the anterior layer, each successive segment insertion and origin is more inferior and deep. Within the posterior layer, each successive segment remains more inferior and deep in origin, but its insertion is more superior.7 Mechanisms include indirect injury such as from weightlifting and gymnastics and less often direct trauma such as shotgun-firing and seatbelt injuries. Indirect injury most commonly occurs during near-maximal eccentric contraction in a mechanically unfavorable extended, abducted, and externally rotated position. This is classically represented at the end of the eccentric portion of a bench-press repetition. Nearly 50% of all cases reported since 1972 have occurred during bench-press.1,3,5,6,8–14 Fiber bundle lengths are relatively shorter and have greater lateral pennation angles in the more inferior segments.7,8 The inferior fibers are lengthened 30% to 45% of their resting fiber length when stretched and receive maximal load with minimal overlap, placing them at a mechanical disadvantage. This combination of fiber bundle length and pennation angle is the prime reason that most tears involve this region of the muscle.7,8 Often, clinical suspicion based on the mechanism of injury combined with the focal physical examination findings leads to the correct diagnosis. The hallmark finding is the asymmetrical contour of the axillary fold when the shoulder is positioned in 90 degrees of abduction, slight extension, and external rotation. Asymmetry can also be seen within the muscle belly with resisted adduction and internal rotation of the shoulder. Palpation of a defect within the axillary fold confirms the suspicion. Often a subcutaneous band passing from the fascia over the pectoralis major into the upper arm remains intact and palpable. Impressive amounts of ecchymosis to the shoulder girdle are commonly present. Although development of a large hematoma is not typical, it should be recognized. Potential complications including life-threatening infections have been reported secondarily; thus the clinician should have an index of suspicion.15–17 Imaging modalities can be used as adjuncts in diagnosis and surgical planning. A standard shoulder radiographic series should be obtained to identify the presence of a bony avulsion, which may alter surgical planning, and also to identify rare concurrent injuries including proximal humeral fractures and shoulder dislocation.18–20 Advanced imaging is best used, to confirm the clinician’s suspicion of a partial-thickness tear that would generally be treated nonoperatively. Visual examination for asymmetry of the axillary fold compared with the contralateral limb should be performed. This can be optimally viewed with the shoulder held in 90 degrees of abduction with external rotation (Fig. 35-1). Manual palpation of the defect in the same position easily identifies the tear.

Management of Pectoralis Major Muscle Injuries

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

Imaging

Surgical Technique

Examination Under Anesthesia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Management of Pectoralis Major Muscle Injuries