CHAPTER 43 Management of chronic shoulder dislocations

Chronic dislocation of the shoulder should be suspected in patients with shoulder pain and decreased range of motion in the context of dementia, alcoholism, obesity, seizure disorders, or multiple trauma.

Chronic dislocation of the shoulder should be suspected in patients with shoulder pain and decreased range of motion in the context of dementia, alcoholism, obesity, seizure disorders, or multiple trauma. A patient with a posterior dislocation is most comfortable in a standard sling and should be fully evaluated.

A patient with a posterior dislocation is most comfortable in a standard sling and should be fully evaluated. Closed reduction of a chronic shoulder dislocation after 3 weeks can be very difficult, and open reduction should be considered.

Closed reduction of a chronic shoulder dislocation after 3 weeks can be very difficult, and open reduction should be considered. Posterior dislocations result in anteromedial humeral head impaction injuries, and anterior dislocations can cause both posterolateral humeral impaction injuries and anteroinferior glenoid bone loss.

Posterior dislocations result in anteromedial humeral head impaction injuries, and anterior dislocations can cause both posterolateral humeral impaction injuries and anteroinferior glenoid bone loss.Introduction

The definition of a “chronic” shoulder dislocation is not clear in the contemporary literature. Various authors have used different cutoff values in the description of chronic dislocations, ranging from 24 hours to 6 weeks.1 For the purposes of this chapter, we agree with Griggs and Iannotti,2 in the use of 3 weeks as the defining time point. Furthermore, a “locked” shoulder dislocation often presents the same management dilemmas and requires similar treatment decisions. This chapter addresses the management of chronic shoulder dislocations; however, parallels with the treatment of a locked shoulder dislocation are acknowledged and can be applied.

Unrecognized glenohumeral dislocations leading to chronic cases are relatively uncommon, with anterior dislocations occurring more frequently than posterior.1 However, in the context of posterior dislocations, a larger percentage is missed because of the difficulty in diagnosis on “standard” radiographs. In addition, patients with a posterior dislocation present to the treating physician in a position of comfort with a sling worn on the abdomen (internal rotation at the side). This adds to the potential for a missed diagnosis with a posterior shoulder dislocation. Fractures also can be present in many of these cases; in fact, Schulz et al3 reviewed 61 chronic dislocations and concluded that 50% had an associated fracture, 33% had neurologic injury, and 28% of these chronic dislocations were posterior. Rowe et al4 also explored the prevalence of chronic dislocations seen by the practicing orthopaedist; 50% of surgeons in practice for 5 to 10 years had seen a chronic dislocation, 70% in practice for 10 to 20 years, and 90% above 20 years. Although it is a rare problem, the orthopaedic surgeon should be comfortable with the diagnosis and potential management options.

Coexistent shoulder pathology must be recognized in the management of a patient with a chronic or locked shoulder dislocation. Often, these patients will develop osteoporosis of the humeral head and softening of the articular cartilage. Significant soft tissue contractures can be present and adhesions may develop between the humeral head the adjacent neurovascular structures with an anterior dislocation. Concomitant rotator cuff tears (sometimes massive) can influence shoulder stability, and subscapularis ruptures with biceps dislocations also may occur. Glenohumeral bone deficiencies can significantly influence joint stability with anteroinferior glenoid bone loss common in anterior dislocations. Defects in the humeral head can create engaging lesions that also impact shoulder stability; these include posterolateral and anteromedial lesions associated with anterior and posterior dislocations, respectively. Overall, an unrecognized shoulder dislocation creates a difficult treatment paradox with functional status, surgical morbidity, and coexisting pathology defining the overall treatment plan.

Chronic posterior dislocation

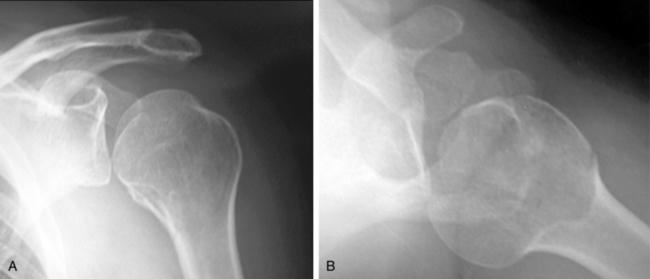

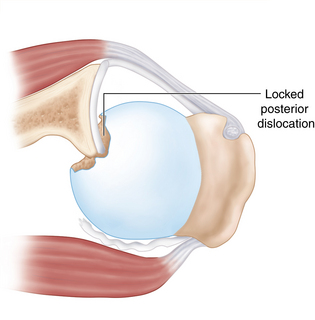

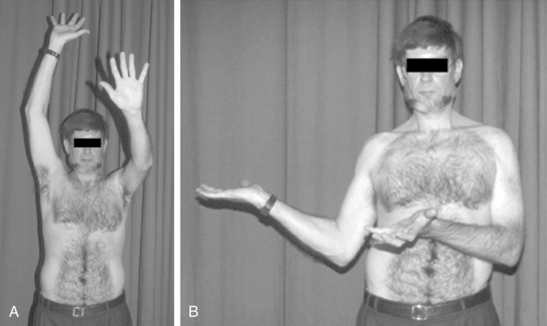

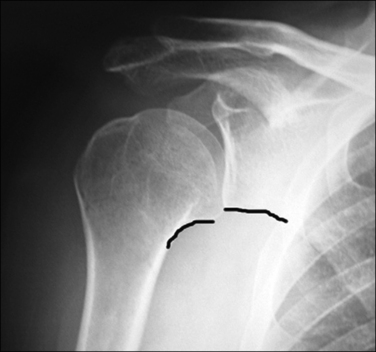

Posterior dislocations comprise approximately 1.5% of shoulder dislocations. Fifty percent of these dislocations are associated with tuberosity, humeral head, or glenoid fractures.5 Posterior capsular tears are invariably present and do have the potential to heal without treatment, as do small posterior glenoid rim fractures. However, posterior dislocations are frequently missed in the initial treatment setting because of an association with distracting variables such as seizures, alcoholism, and severe trauma. This fact, coupled with the subtlety of findings on an anteroposterior radiograph (Fig. 43-1), increases the potential for a posterior dislocation to become a chronic unrecognized problem. In addition, patients also present in a position of comfort with the arm in an internal rotation sling held against the abdomen. However, clinical suspicion and a thorough examination will reveal a decreased range of motion (ROM) and a diagnosis of a locked glenohumeral joint dislocation (Fig. 43-2).

In fact, Rowe et al4 noted that the initial treating physician failed to diagnose a posterior dislocation in up to 79% of cases. Checchia et al6 also reviewed 66 patients with a total of 73 posterior fracture dislocations of the shoulder and found that over 50% of the chronic cases were initially misdiagnosed. Thus, an appropriate workup with an axillary lateral radiograph and physical examination is mandatory in the context of shoulder pain or decreased motion involving the patient populations noted above. Specifically on examination, the shoulder will be locked when trying to externally rotate a posterior dislocation (see Fig. 43-2).

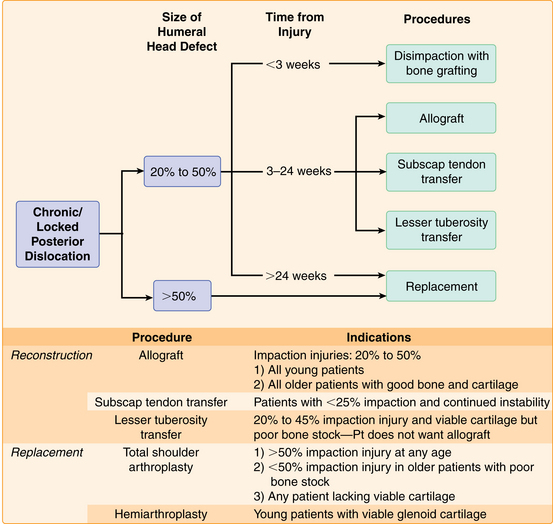

In the setting of a chronic or locked posterior dislocation there is almost invariably a large anteromedial humeral head defect or impression fracture, as well as posterior glenoid bone loss or erosion7 (Fig. 43-3). The size of these defects and the stability of the shoulder will dictate treatment in conjunction with the functional demands of the patient. Treatment can range from nonoperative management to prosthetic replacement with a variety of intermediate options.

Indications/contraindications

The following section outlines and describes the available alternatives. There is a discreet decision analysis that occurs during the development of a treatment plan (Fig. 43-4).

Preoperative history, examination, and radiographic findings

Examination findings

Pathognomonically, these patients will have an external rotation deficiency with a mechanical block to anything past neutral (see Fig. 43-2). They also often will have a limitation in abduction to less than 60 degrees. However, in chronic cases, there is a potential that the humeral head has remodeled enough to permit limits beyond those cited, as well as allowing the patient a functional ROM.

Radiographic findings

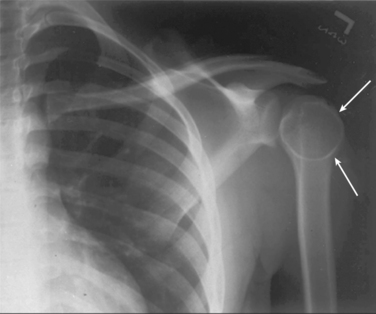

Plain radiographs can confirm the diagnosis of a posterior dislocation; however, the appropriate views must be taken. Often, the patient with an acute dislocation will present with a painful shoulder and the treating physician will fail to obtain correct diagnostic imaging. On an anteroposterior (AP) view the dislocated shoulder can appear normal (see Fig. 43-1). However, there are also subtle findings present on the AP radiograph. These include; the loss of normal joint space, overlap between the humeral head and the glenoid rim, the “light bulb” sign (Fig. 43-5, an internally rotated view of the humeral head), and a break in “Moloney’s line” (Fig. 43-6, analogous to Shenton’s line in the hip). Nonetheless, the best view in the evaluation of a posterior dislocation is the axillary lateral.

FIGURE 43-6 ‘‘Moloney’s line’’ makes a continuous arc from the inferomedial humeral calcar to the inferior aspect of the glenoid. This line can be disrupted with a posterior dislocation, similar to the break in Shenton’s line with hip dysplasia.

(From Levine WN et al: Traumatic posterior glenohumeral dislocation: classification, pathoanatomy, diagnosis, and treatment. Orthop Clin N Am 39(4): 519–533, 2008.)

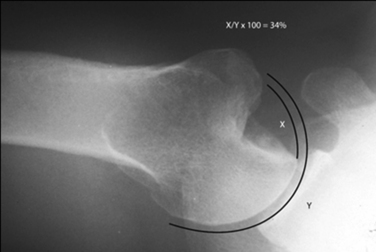

The axillary lateral view also will provide important information regarding the amount of glenoid involvement and any impaction of the humeral head. The degree of impaction can be quantified by estimating the size of the defect and comparing it to the arc of the articular surface (Fig. 43-7). All images also should be evaluated for any associated fractures. The associated fracture rate of the humerus and tuberosities has been reported to be as high as 50%.8 If any osseous involvement is noted on plain radiographs, a computed tomography (CT) scan is recommended to further evaluate the amount and location of bony involvement.

FIGURE 43-7 Estimation of the size of humeral impaction (X/Y × 100 = % impaction).

(From Chen AL et al: Management of bone loss associated with recurrent anterior glenohumeral instability. Am J Sports Med 33(6):912–925, 2005.)

Description of technique(s)

Conservative management

Despite the anatomic deformity and severe losses in glenohumeral rotation, a chronic posterior dislocation can be surprisingly well tolerated, especially in the elderly or debilitated patient (Fig. 43-8).5 In these cases, the patient may regain enough ROM for activities of daily living with minimal pain. Thus, it is important to balance surgical morbidity with expected outcomes. Hawkins et al8 reported on 41 patients with locked posterior dislocations and 7 patients received no treatment. Of these patients, only two had enough function to raise the hand to the level of the head. On final follow-up, pain ratings did not worsen and the functional losses did not progress beyond the immediate postinjury losses. Schulz et al3 also noted that the 5 patients in his nonoperative group had a fixed internal rotation deformity and elevation averaged 40 degrees. These patients did not gain a significant increase in ROM with physical therapy.

Closed reduction

Closed reduction can be an option if the dislocation meets the following criteria:

However, some authors also state that an attempt at reduction can be done if the dislocation is less than 6 weeks old and the radiographs demonstrate a humeral head defect less than 20% of the articular surface.5 In the series by Schulz et al,3 reduction was successful in 19 of 30 cases that were dislocated for 4 weeks or less, but succeeded in only 1 patient of 10 that had been dislocated in excess of 4 weeks.

Open reduction

Open reduction is often required if the injury is greater than 3 weeks out, if the shoulder is locked, or if more than 25% of the humeral head is involved.2 The following factors should be taken into consideration during surgical planning:

Once open reduction has been completed, a variety of procedures address the coexistent pathology (see Fig. 43-4).

Disimpaction and bone grafting

Disimpaction and bone grafting of the humeral head defect can be considered in the patient with a relatively acute injury, less than 50% of the humeral head involved, and viable articular cartilage.9 However, the patient should have adequate bone stock for buttress fixation.

Technique (Fig. 43-9)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree