Management of Anterior Translation of the Talus During a Total Ankle Replacement

J. Chris Coetzee

INTRODUCTION

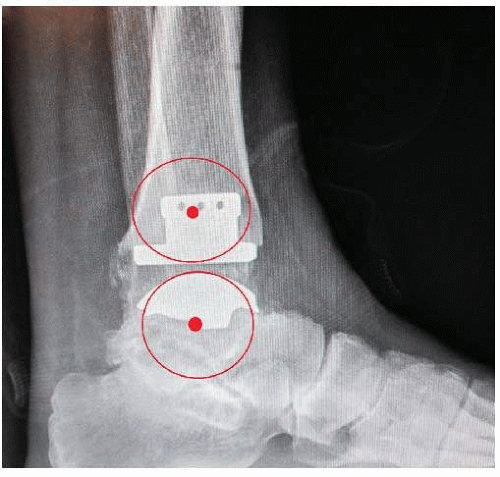

There is an increasing evidence in the literature that misalignment of components in any plane will have a negative effect on the outcome of ankle replacements. Barg et al.1 showed in a retrospective study including 317 total ankle replacement patients that anterior or posterior positioning of the talar component in relation to the tibia resulted in worse functional outcome score and less pain relief (Fig. 11.1).

Similarly, Trincat et al.2 showed that it is possible to correct preoperative coronal plane deformities with an ankle replacement and that there is a high failure rate if the coronal deformity recurs.

Figure 11.1. This shows an ankle where the talus is perfectly centered under the tibia, which affords the ankle replacement the best change for longevity and best functional results. |

Espinosa et al.3 also confirmed in a very eloquent study that component misalignment will significantly increase contact pressure and could therefore lead to earlier failure.

Anterior translation of the talus is reasonably common. It poses varying degrees of difficulty to center the talus under the tibia, and a good working understanding of the etiology and treatment options is needed to address this during surgery.

ETIOLOGY OF ANTERIOR TRANSLATION OF THE TALUS

The etiological factors can be divided as skeletal and soft tissue abnormalities. As expected, often one might lead to the other, and by the time surgery is done, there is a combination of both. It is critical to address all the components of the deformity to ensure a reliable result. The skeletal factors include anterior tibial erosion or collapse secondary to a tibial plafond or ankle fracture, which is most common. Partial avascular necrosis of the talar body can result in collapse and anterior subluxation of the talus.

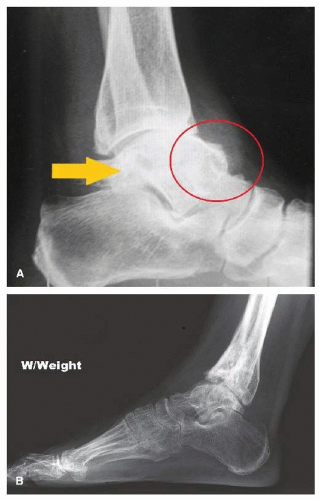

By far the most common etiology for anterior subluxation, though, is chronic lateral ankle instability. With loss of the restraint of the anterior talofibular ligament, the talus tends to rotate anteriorly out of the ankle, and over time there is progressive wear of the lateral side of the talus and the corresponding area of the tibia. This could lead to flattening of the tibial plafond and therefore loss of the skeletal constraint of the ankle stability as well. An equinus contracture could also add an anterior translation force across the ankle (Fig. 11.2A, B).

There is limited discussion in the literature about the management of anterior translation of the talus. The challenge is to reliably center the talus under the tibia.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

As mentioned before, there are two main modes of failure, skeletal and soft tissue, and one should be aware of both in planning the reconstruction. On occasion, both elements could be present. With significant anterior erosion of the tibia, the ligaments might fail with time due to constant overstress.

During the physical examination, one should specifically evaluate the ligamentous integrity of the ankle. If the ankle is clearly unstable, one should plan to address the soft tissue balancing during surgery. If there is an equinus contracture, it might prevent the talus from sliding back under the tibia.

With anterior tibial erosion or posttraumatic collapse, the deltoid and lateral ligament complex could be functionally short or contracted and thereby prevent the talus from reducing.

Figure 11.3. A: Maximum weight-bearing dorsiflexion with the knee bend is shown. B: Maximum plantar flexion is shown. These views should be routine for all x-rays of ankle assessment. |

Weight-bearing x-rays are essential to evaluate the amount of anterior subluxation. The x-rays should include not only the standard anteroposterior, lateral, and mortise views, but also the maximum plantar flexion and dorsiflexion lateral views. The maximum dorsiflexion view will give one some idea about the ability to reduce the subluxation, especially in the ligamentous lax ankles (Fig. 11.3A, B).

GENERAL CONCEPTS

Place a towel stack or something similar under the distal tibia to allow the talus to translate posterior. Always do an adequate or aggressive medial and lateral gutter debridement to ensure the talus can rotate back in position. It is commonplace to have heterotopic bone buildup, especially in the lateral gutter.

One should have a low threshold to do a gastrocnemius or Achilles lengthening. An ankle in equinus after surgery has a tendency to force the talus forward. There should be a minimum of 10° of dorsiflexion at the end of surgery.

As a general rule, the skeletal deformities are easier to address.

STEPWISE TECHNIQUE

1. A towel stack is placed under calf to allow the ankle to “slide back.”

a. The usual midline anterior incision is used (see video 11.1).

b. In some cases, there may be a significant amount of heterotopic bone that has formed over the neck of the talus. This will not only obscure the normal contour of the talar dome, but, for most of the current implants available, also make it more difficult to place the talar cutting guide in the correct position. It is imperative to aggressively resect osteophytes off the talar neck in order to simulate the normal contour of the bone.

c. The most common mistake is to place the talar cutting guides too anterior on the talus, irrespective of the system used. This will cause the talar implant to be placed anterior. To avoid this, the contour of the talar body should be corrected to allow the talar cutting block to sit under the center of the tibia. This position should be confirmed under fluoroscopy prior to performing the first talar cut (Video 11.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree