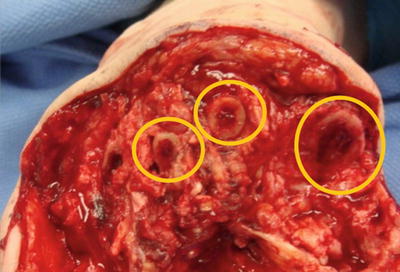

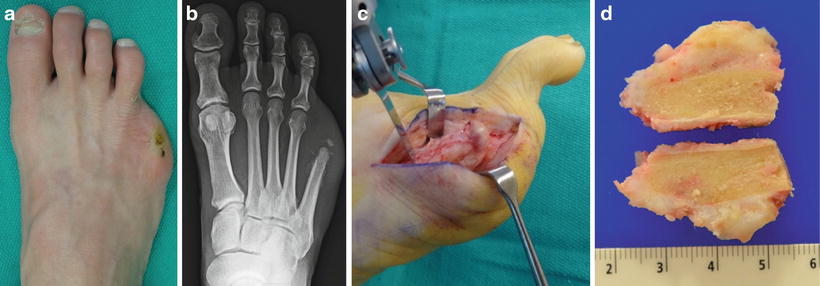

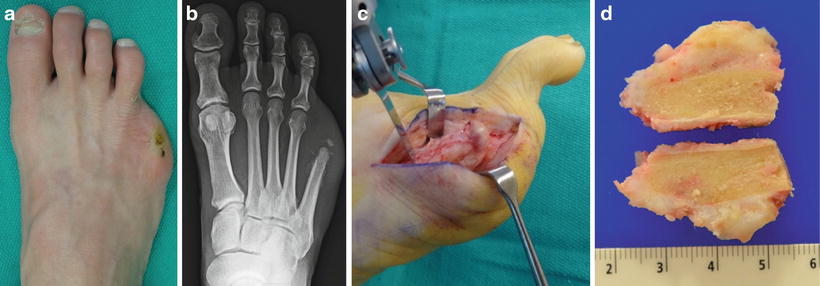

Fig. 12.1

Heterotopic ossification is most frequently appreciated at partial metatarsal amputation sites. It becomes clinically relevant when mid- to high-grade ossification forms on the plantar weight bearing aspect of the foot. Re–published with permission of the Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery [30]

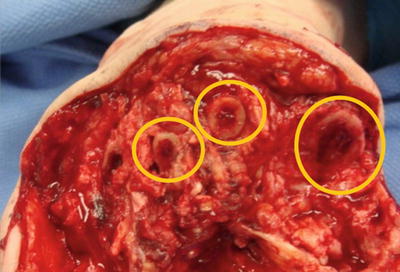

Fig. 12.2

Clinically relevant heterotopic ossification is appreciated at a previous partial fifth metatarsal amputation site. Complete fifth ray resection with staged surgery requiring peroneal tendon transfer into the cuboid was performed due to the development of osteomyelitis at the initial resection site

Heterotopic ossification is a phenomenon that has been well described in the hip, knee, and upper extremities [2–12]. It can be classified into the following categories based on etiology: posttraumatic, nontraumatic or neurogenic, and myositis ossificans progressiva or fibrodysplasia ossificans progressive [13–29]. Posttraumatic HO includes surgically induced etiologies and is the focus of this chapter. It has been documented as the most common complication following total hip arthroplasty with a mean incidence of 53 % [22]. Prophylactic measures are often employed in such settings. While being well recognized throughout the body, HO following local amputation in the foot has historically received little attention from a clinical or research standpoint. However, in a retrospective cohort of 72 patients who underwent amputation consisting of partial metatarsal or transmetatarsal amputation, Boffeli and colleagues found a 75 % incidence of postoperative HO formation by 10 weeks postoperatively. Nearly three-quarters of patients who formed HO exhibited mid- to high-grade bone growth with 18.5 % of patients exhibiting an HO-associated ulcer requiring repeat surgical resection [30]. Similarly, the incidence of heterotopic bone growth after metatarsal head resection in the setting of rheumatoid arthritis has been reported as high as 72 %, most commonly on the second and third metatarsals [31].

Several medical and surgical prophylactic measures are available to decrease the potential for HO. Medical prophylaxis mainly consists of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications or single-dose radiation treatment, which are often advocated in patients deemed at high risk for developing HO. Radiation is performed perioperatively in conjunction with surgical intervention. Additionally, certain surgical techniques and practices can minimize the potential for complicating HO. Given the high incidence and potential for complication, such prophylactic measures are important in limiting local amputation-associated morbidity.

Etiology of Heterotopic Ossification

The specific cause of heterotopic ossification remains elusive. It is felt that mesenchymal stem cells are introduced into the soft tissues secondary to violation of bone and exposure of bone marrow from trauma or surgery, although these pluripotent cells can also be derived from adjacent muscle. These stem cells then differentiate into osteoblasts in the soft tissues and undergo osteogenesis [32]. While the impetus for stem cell differentiation remains unclear, the likely responsible factor is bone morphogenetic protein derived from traumatized tissue [33]. This differentiation appears to begin at approximately 16 h and peaks at 32 h postoperatively [34].

The typical scenario for clinically relevant HO involves a patient undergoing partial foot amputations secondary to osteomyelitis, soft tissue infection, gangrene, or trauma with exposed medullary bone at the amputation site (Fig. 12.3). The periosteum and endosteum of bone contain the main supply of osteoprogenitor cells [35]. When performing a bone cut, the periosteum is often stripped before the cut is advanced through the medullary canal. Thus the periosteum and endosteum are both violated by the local trauma associated with the amputation, exposing a maximal amount of osteoprogenitor cells to the adjacent soft tissue. Hematoma derived from the medullary canal likely provides a vehicle for transfer of the osteoprogenitor cells into the soft tissues immediately adjacent to the amputation site, placing patients with robust vascular status at higher risk of HO formation [35].

Fig. 12.3

Exposed medullary bone at the amputation site creates a portal for osteoprogenitor cells from the endosteum to extravasate into the soft tissues and differentiate into bone-forming osteoblasts

Clinical Presentation

In order to appreciate the clinical presentation of HO, it is important to have an understanding of the risk factors that predispose the patient to heterotopic bone growth. The top predictor for whether HO can be anticipated is a prior history of formation [36]. Sufficient vascular status to the extremity may place the patient at higher risk as well, as those with peripheral vascular disease have exhibited a 30 % lower risk [37]. Furthermore, while diabetes and peripheral neuropathy are not independent risk factors [37], these are relative risk factors as diabetic neuropathic patients are at higher risk for amputation [38]. Less common risk factors are alkaline phosphatase and bone-forming disorders, such as ankylosing spondylitis or Paget’s disease. Race and age have not been shown to be strong predisposing factors [39].

Signs and symptoms of actively forming HO can present from 3 to 12 weeks postoperatively [40]. There is often more swelling and erythema at the surgical site that persists longer and to a greater extent than would be anticipated with normal healing. Such findings may appear similar to postoperative infection, which should be ruled out. Serial postoperative radiographs are instrumental in monitoring for HO. We have appreciated radiographic changes as early as 4 weeks and as late as 10 weeks postoperatively [37]. For the purpose of determining the extent of HO involvement, Boffeli and colleagues developed a staging system similar to those created for the hip [30, 41, 42] (Table 12.1). The first radiographic sign of HO may be a soft tissue mass near the amputation site. Ossification typically begins in the soft tissues adjacent to the bone resection site, so early radiographic appearance of bone is often circumferential radiodensity with a lucent center [39]. There may be several foci of ossification within the osteoid. At this stage, bone frequently resembles an isolated bone island and is characterized as grade I (Fig. 12.4a). As the callus continues to ossify, it often adjoins to the original bone and the radiodense portion continues to enlarge (Grades II and III) (Fig. 12.4b, c) [30]. The bone continues to remodel until approximately 30 months postoperatively, when the pattern of heterotopic bone closely resembles that of normal bone [23].

Table 12.1

Metatarsal resection HO staging

Grade 0—No heterotopic ossification | |

Grade I—Isolated bone island adjacent to resection site | a—No adjacent ulceration |

Grade II—Adhered bone spur formation <1cm | b—Adjacent ulceration |

Grade III—Adhered bone spur formation >1cm |

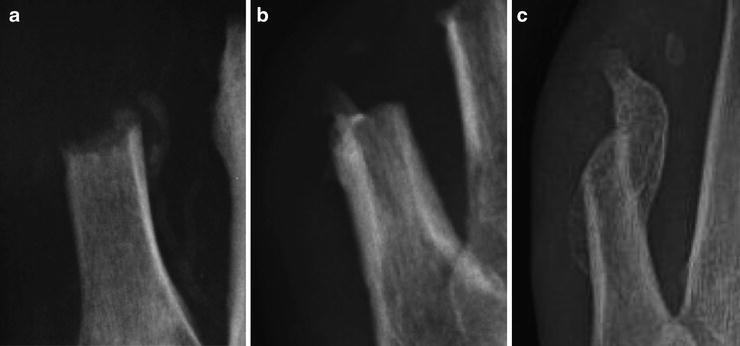

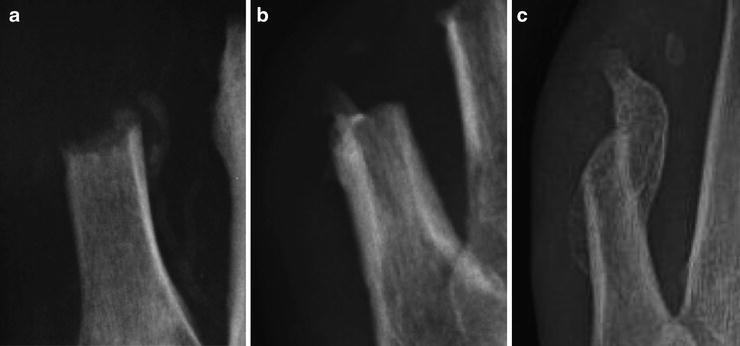

Fig. 12.4

(a) Grade I heterotopic ossification exhibits a rim of radiodense bone formation with a center of lucency. (b) As heterotopic ossification progresses, it may attach to the original bone, indicated as Grade II formation. (c) Advanced Grade III heterotopic ossification is classified as bone growth greater than 1 cm on radiograph

Patients who have previously undergone partial foot amputation and develop subsequent neuropathic ulcers or pre-ulcerative lesions should be assessed for the presence of HO as a possible etiology. In particular, bone formation on the plantar weight bearing portion of the foot would pose the most substantial threat. HO-related ulcers are often full thickness in depth due to the concentrated peak plantar foot pressure created during weight bearing by relatively discrete HO prominences. Thus concomitant osteomyelitis may be present as well. The practitioner should not assume that radiographic appearance consistent with HO precludes the diagnosis of osteomyelitis, as both can be present in conjunction with one another. Laboratory analysis and advanced imaging may be warranted in this situation. While bone scans, ultrasonography, and computed-tomography imaging has been used for diagnosis of HO in the hip, this has not been assessed in the foot. We do not routinely use such modalities but will consider magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine the presence of soft tissue abscess or osteomyelitis. The typical appearance of heterotopic ossification on MRI is a low-signal-intensity rim with a heterogeneous, high-signal-intensity tissue structure [43].

Treatment and Prophylactic Measures

Clinically relevant heterotopic ossification often requires surgical intervention either for non-healing wounds that have failed appropriate offloading measures or in patients who have developed secondary osteomyelitis. In our experience, while offloading measures may allow the wound to improve or heal, the re-ulceration rate is high in patients with HO-induced neuropathic ulceration. In the patient with acute soft tissue infection or osteomyelitis, surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment. Goals of surgery are to correct structural deformity, resect potentially infected bone for biopsy purposes, avoid recurrent HO, and allow for primary closure of soft tissues. Intraoperatively, it is often difficult to dissect heterotopic bone growth from adjacent soft tissues as the two are intimately affixed. Care is taken to ensure that all bone growth is excised not only when attached to the adjacent bone but also when isolated islands are present in the soft tissues as these could be a source of pressure if not removed. Oftentimes during direct intraoperative inspection, the degree of involvement appreciated at the HO site appears much more extensive than preoperative radiographs would indicate as abnormal tissue that fails to fully ossify may not be evident on radiograph (Fig. 12.5). When excising heterotopic bone, it is often necessary to resect proximal to the previous resection site in order to obtain a clean margin in the event of osteomyelitis and for sufficient soft tissue coverage if necessary (Figs. 12.6 and 12.7).

Fig. 12.5

(a) Clinical appearance of a patient who had undergone previous partial fifth ray resection whose surgical wound never fully epithelialized and became a source of pain postoperatively. (b) Radiographs would suggest minimal HO involvement, but (c) intraoperative findings revealed abnormal tissue with extensive involvement at the previous resection site. (d) Sectioning of the metatarsal resection site reveals a large prominence on the plantar aspect of the bone not fully appreciated on preoperative radiographs. Pathologic analysis revealed no signs of osteomyelitis at the resection site

Fig. 12.6

(a) Preoperative radiographs of extensive heterotopic bone growth with associated full-thickness neuropathic ulcer and osteomyelitis. (b) Postoperative radiographs reveal the level of resection required in this situation to allow sufficient soft tissue closure and obtain noninfected margins as confirmed by pathology. While disarticulation at the first tarsometatarsal joint can decrease the likelihood of forming HO, retaining the metatarsal base serves to maintain stability by preserving the insertion of the tibialis anterior and peroneus longus tendons. Subsequent postoperative radiographs revealed no signs of HO recurrence when treated with single-dose radiation therapy. Re-published with permission of the Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery [30]

Fig. 12.7

(a, b) Preoperative clinical and radiographic appearance of clinically relevant heterotopic ossification. (c, d) Postoperative clinical and radiographic appearance following complete fifth ray resection with staged surgery requiring peroneal tendon transfer into the cuboid. Disarticulation decreases the likelihood for recurrent heterotopic ossification as opposed to repeat resection through the metatarsal.

The resected bone is sent for pathologic analysis to confirm heterotopic ossification and possible concomitant osteomyelitis. Histologically, well-developed HO appears as cancellous and mature lamellar bone with associated blood vessels and bone marrow as well as low-grade hematopoiesis. Edema, hypersensitivity, muscle necrosis, and osteoporosis may surround HO and be a consequence of it rather than a cause (Fig. 12.8) [44]. The medical and surgical preventative measures discussed below should routinely be applied at this time to avoid repeat heterotopic bone growth. Two main preventative measures have traditionally been advocated for patients deemed at particular risk for HO formation: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and radiation therapy. Furthermore, certain routine surgical techniques and approaches can minimize the potential for developing HO.

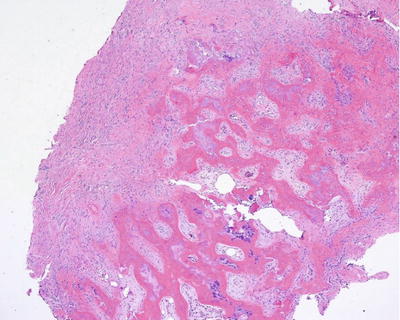

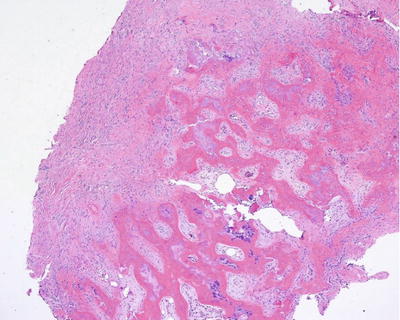

Fig. 12.8

Histologic features of heterotopic ossification. Culture and pathology specimens should be collected intraoperatively to confirm the diagnosis of heterotopic ossification and possible concomitant osteomyelitis

Surgical Prophylaxis

Appropriate surgical technique during the initial amputation procedure can help minimize the development of complicating HO and should be the standard for all amputation procedures. While there is higher potential for heterotopic bone growth in any region where the medullary canal is exposed to adjacent soft tissues, there should be a higher level of concern when amputating through the metatarsals. This level of amputation seems particularly prone to clinically relevant HO likely due to the void left adjacent to an open medullary canal, which predisposes the patient to hematoma formation. Extravasation of hematoma from the medullary canal likely carries osteoprogenitor cells that will ultimately differentiate into bone-forming osteoblasts, so any efforts to minimize local hematoma formation at the resection site will be beneficial. We often utilize a staged surgical approach, with the majority of bone being resected in the initial surgery for purposes of infection source control. This often allows cellulitis to resolve prior to subsequent repeat irrigation and hematoma evacuation followed by delayed primary closure within a few days. In patients deemed at high risk for hematoma formation, such as in the setting of anticoagulation therapy or robust vascular status, staged surgery with dead space management using antibiotic beads can be employed. This approach can also be utilized when residual osteomyelitis persists after resection when parenteral antibiotics in isolation may not be sufficient. After initial incision and drainage and antibiotic bead application, stage 2 typically occurs 2 weeks later and consists of antibiotic bead removal with irrigation and evacuation of hematoma (Fig. 12.9).

Fig. 12.9

A staged surgical approach is a valuable adjunct to avoiding heterotopic ossification. Antibiotic-impregnated beads are applied in the dead space created at the resection site during the initial surgery. The secondary staged surgery typically occurs 2 weeks later and involves bead removal, evacuation of organized hematoma that could promote HO formation, proximal margin biopsy, minimal soft tissue debridement as needed, and delayed primary closure. Oftentimes the proximal margin biopsy is obtained from curettage of the medullary canal as opposed to resection of a segment cortical bone in order to preserve metatarsal length

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree