Lyme Disease

William F. Iobst

Kristin M. Ingraham

|

A 39-year-old white male presents to your office with a 3-month history of a painful, swollen left knee. He currently denies other significant joint pain, but describes what he thought was a flu-type illness, characterized by fatigue, headache, malaise, and arthralgias 3 to 4 months prior to the onset of his knee pain. He also notes altered sensation in his hands and feet. He has no history of knee injury, and believes that use of over-the-counter ibuprofen has helped take the edge off the pain. This medication has not reduced the swelling or sensation of warmth when he touches the knee.

The patient lives in rural southeastern Pennsylvania, and is an active hunter. He denies family history of arthritis or arthritis-related diseases. He is aware that Lyme disease is a common illness in this area and wonders if he in fact has this illness.

Introduction

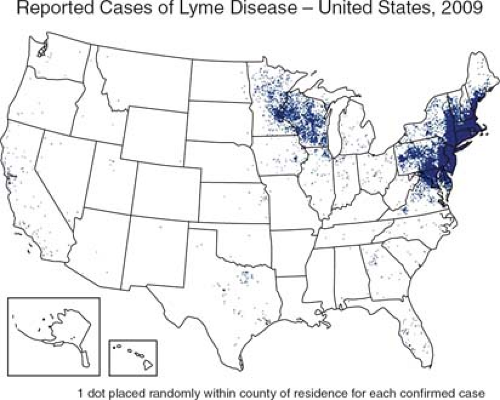

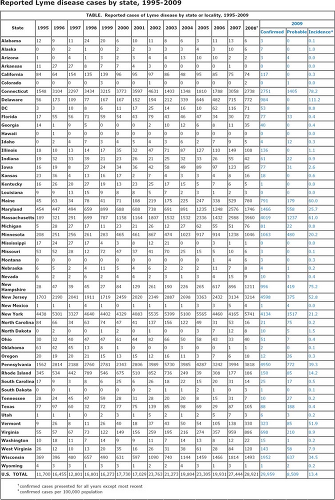

The clinical presentation described above is that of late-stage Lyme disease. While Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne illness in the United States, accurate diagnosis requires an appreciation of regional variation in disease prevalence (Fig. 24.1). Lyme disease is endemic in the northeastern, midwestern, and western regions of the United States. In 2009, approximately 30,000 cases of confirmed and suspected disease were reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The states with the highest total number of reported cases are New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. The highest incidence of disease occurred in Delaware and was reported at 111.2 per 100,000 individuals (Fig. 24.2).

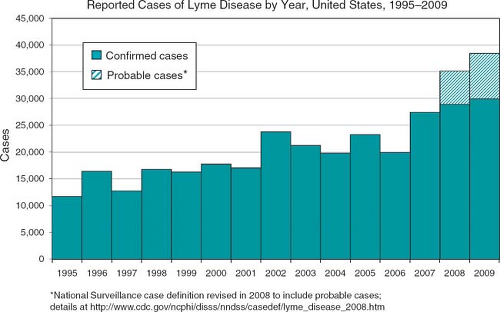

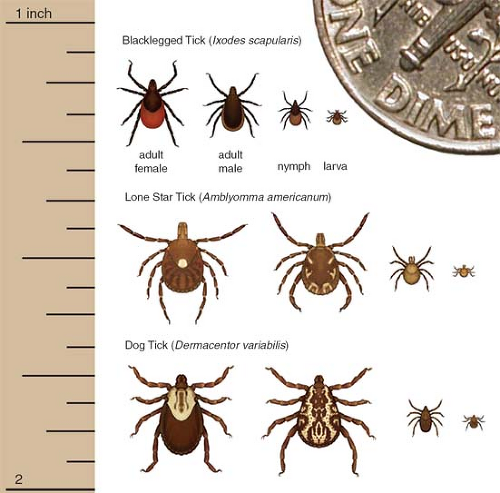

Effective prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of this disease also require an understanding of the prevalence, transmission vector, and natural history of Lyme disease. The disease is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted through the bite of the black-legged tick or deer tick Ixodes scapularis (Fig. 24.3). The spirochete is most frequently transmitted by the bite of the nymphal stage of the tick in the spring of the year. The nymphal-stage tick is very small, not being larger than a poppy seed (Fig. 24.4). Less frequently, adult ticks transmit the disease in the fall of the year. Cases typically cluster in children younger than 15 years and in middle-aged adults, and are associated with histories of outdoor activities that expose individuals to the tick. Lyme disease is a reportable illness and both confirmed and probable cases have been tracked by the CDC since 1995. From 1995 to 2009, more than 400,000 cases of confirmed and probable Lyme disease have been reported with the number of cases increasing on a yearly basis (Fig. 24.5). While infection with B. burgdorferi is a worldwide occurrence, this chapter discusses only the manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of this illness in North America.

Figure 24.4 Dime ticks transmission and size. Image accessed January 11, 2011, at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/lyme/ld_transmission.htm. |

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of Lyme disease is generally divided into three stages: early localized, early disseminated, and late-stage disease. Two additional stages have also been described, but are not universally accepted as part of the natural history of the disease. An understanding of these stages is critical for effective diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease.

Early Localized Disease

Early localized Lyme disease occurs within days to up to 1 month of initial tick bite and is characterized by a skin rash and constitutional symptoms including malaise, fatigue, headache, mild stiff neck, myalgias, and arthralgias. Examination can reveal regional lymphadenopathy. Erythema migrans (EM) occurs in only 80% of patients diagnosed, and only 25% of patients with this rash ever recall a tick bite. Furthermore, not all patients present with the classically described skin rash. The classical rash has an expanding and slightly raised erythematous border with an area of central clearing and is frequently referred to as a “target lesion” (Fig. 24.6).

Early Disseminated Disease

Early disseminated disease typically occurs within a few weeks to months after tick bite, and can present in the absence of a clear history of early localized disease. In addition to constitutional symptoms similar to those described in early Lyme disease, patients can present with musculoskeletal, neurologic, and cardiac symptoms. Approximately 60% of patients report migratory arthralgias; 15% experience neurologic symptoms, which can range from meningitis (lymphocytic), encephalitis, cranial neuropathy (facial nerve), peripheral neuropathy, myelitis,

and cerebellar ataxia. Up to 8% of patients develop cardiac abnormalities. Cardiac abnormalities frequently present with symptoms of light-headedness, palpitations, and syncope. Heart block is the most frequent abnormality and can occur in up to 8% of patients. Heart block can range from first degree to complete heart block. Myocarditis has also been reported but is rare.

and cerebellar ataxia. Up to 8% of patients develop cardiac abnormalities. Cardiac abnormalities frequently present with symptoms of light-headedness, palpitations, and syncope. Heart block is the most frequent abnormality and can occur in up to 8% of patients. Heart block can range from first degree to complete heart block. Myocarditis has also been reported but is rare.

Clinical Points

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne illness in the United States.

Cases are most commonly seen in children younger than 15 years and in middle-aged adults.

Effective treatment requires an understanding of the three stages of Lyme disease and an understanding that not all patients report progressing through each of these stages.

Persistent symptoms following appropriate treatment of Lyme disease should prompt reinvestigation for other potential comorbid disease states.

Late-Stage Disease

Late-stage disease occurs months to years following tick bite. Musculoskeletal symptoms are the most common finding in late-stage disease, with slightly more than half of patients developing intermittent mono- or oligoarticular arthritis. Approximately 10% of patients develop persistent monoarthritis of the knee. Even with appropriate treatment, a small number of late-stage patients persist with objective finding such as mono- or oligoarthritis. Persistence of these findings is not an indication to extend antibiotic therapy. Currently there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that such findings are due to ongoing active infection unless there is reason to suspect treatment noncompliance. One potential explanation for ongoing joint manifestations following appropriate antibiotic therapy is the development of a secondary autoimmune response in the joint. Posttreatment joint symptoms typically subside within months to a few years and do not necessarily require additional treatment. Ongoing symptomatic joint pain can be treated with anti-inflammatory medications.

Late-stage patients can also present with chronic low-grade encephalopathy, encephalomyelitis, and/or peripheral neuropathy. Peripheral neuropathy typically presents with paresthesias in the setting of unremarkable sensory and motor examinations. These symptoms are similar to those of early disseminated disease, and differentiating between early disseminated and late-stage disease can be difficult unless there is a clear history of tick bite or early stage symptoms. Encephalopathy and encephalomyelitis can present years after infection and can be subtle and difficult to diagnose.

In addition to the three classical phases of Lyme disease, clinicians should be aware of two additional, but controversial, stages called “post–Lyme disease syndrome” and “chronic Lyme disease” (1).

Chronic Lyme disease describes a condition some physicians and patients believe to be persistent B. burgdorferi infection. Frequently, these patients have no reproducible or convincing scientific evidence linking symptoms to B. burgdorferi infection.

Chronic Lyme disease can be approached as having four categories. In category one, patients present with nonspecific symptoms with no objective clinical or laboratory evidence of infection.

In category two, patients present with a history of potential Lyme disease, by have evidence of illness other than Lyme disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree