Lisfranc Injuries

George F. Wallace

Lisfranc injuries are relatively uncommon, yet missed upward of 20% of the time (1). The incidence has been reported to be 1 per 55,000 and represents 0.2% of all fractures (2). Naturally, the injury occurs at the Lisfranc joint and has been historically designated precisely as a “Lisfranc fracture dislocation.”

Therefore, one can have a Lisfranc dislocation with or without a fracture. However, there can be any number of combinations of a fracture or fractures of one or numerous osseous segments comprising the Lisfranc articulation with a dislocation or dislocations. The Lisfranc joint is also called the tarsometatarsal joint comprising articulations of all five metatarsal bases with the distal three cuneiforms and cuboid articulations, respectively. Conventionally, injuries at the Lisfranc joint are designated as a Lisfranc fracture dislocation. When fractures are absent, then a Lisfranc dislocation can be listed as the diagnosis.

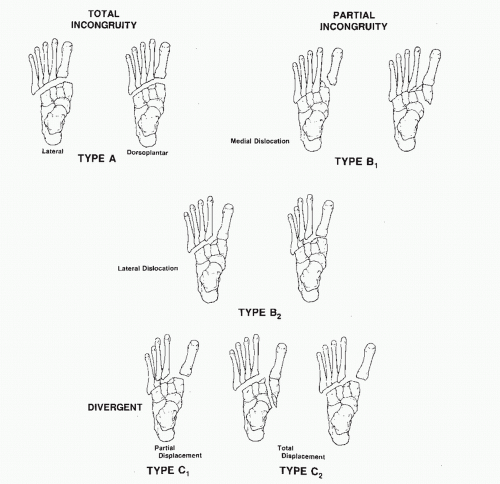

A few classifications have been proposed: Quenu and Kuss, Hardcastle, and the Myerson modification to the latter (3,4). None include any prognostic indicators. Moderate interrater reliability was demonstrated by Talarico et al (5) upon analysis of Hardcastle’s classification. Intuitively, however, the more joints disrupted, either by dislocation and/or fractures, the more severe the injury and the greater the potential for longterm sequelae (Table 116.1; Fig. 116.1). One need not have a fracture of the joint to initiate the classification scheme.

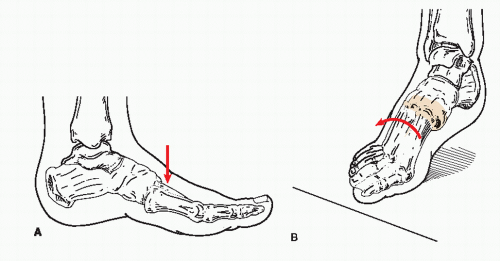

Two mechanisms of injury have been proposed: the “direct” due to a force applied at the Lisfranc joint, for example, a heavy object falling on the joint, and the “indirect” from forces applied resulting in plantarflexion and an amount of rotation at the Lisfranc joint (6). In either, the degree of force will determine if fractures are present along with the dislocation as the end result (Fig. 116.2).

As in all trauma, index of suspicion has to be present whether or not disruption of any part of the Lisfranc joint has occurred. The joints may be aligned due to spontaneously reducing without evidence of a fracture, but a cogent history and physical examination will most likely point the clinician toward the diagnosis. Stressing the joints may then be warranted.

EVALUATION AND DIAGNOSIS

The recessed second metatarsal into the intermediate cuneiform serves as the keystone to the longitudinal arch and Lisfranc joint. The depth of this articulation may play a role whether the joint will dislocate when provoked (7). The more shallow the joint, the greater risk for injury.

The Lisfranc articulation has numerous ligaments. The dorsal ones are the weakest and lead to a greater predominance of dislocations in that direction. The infamous Lisfranc ligament is the only one named specifically. It is an interosseous ligament between the medial cuneiform and second metatarsal and is the strongest. The first metatarsal has no similar attachment and thus easily dislocated.

Patients present with a history of either something striking directly at the Lisfranc joint or a mechanism whereby the joint is stressed in a plantar direction with a rotary component. Tripping, awkwardly stepping into a pothole, or a motor vehicle accident may be a few of the many ways patients can recount their experience. The latter is becoming all too familiar. As airbags protect the head and torso, the lower extremity is offered no such aid (8) (Fig. 116.3). Likewise, someone may be admitted for multitrauma with failure to diagnose a pedal injury, which becomes overt only when the patient begins ambulation.

The foot may be grossly malaligned. Occasionally, the Lisfranc joint may have to be stressed to determine if one has a dislocated joint that has spontaneously reduced. Fluoroscopy may be utilized for visualization. Nerve blocks, sedation, or general anesthesia can be administered to facilitate stressing the joint. There are basically two maneuvers to stress the joint:

While stabilizing the rearfoot, apply an adductory/supinatory force on the lateral aspect around the fifth metatarsal base, then an abductory/pronatory force near the first metatarsal base (Fig. 116.4).

Each metatarsal base is stressed in a dorsal and plantar direction while grabbing the metatarsal head, which has been previously called the “piano key test” (9). Excessive movement especially dorsally is positive for disruption of the joint.

Both of the above can be used even in the patient presenting with an old injury.

Radiographs obtained in all three views are essential. Although one can see a lowering of the arch on a lateral weightbearing view, this type of film should be reserved for those without pain or when assessing a missed Lisfranc injury far removed from the index event. Otherwise, plain films can be ordered non-weight-bearing.

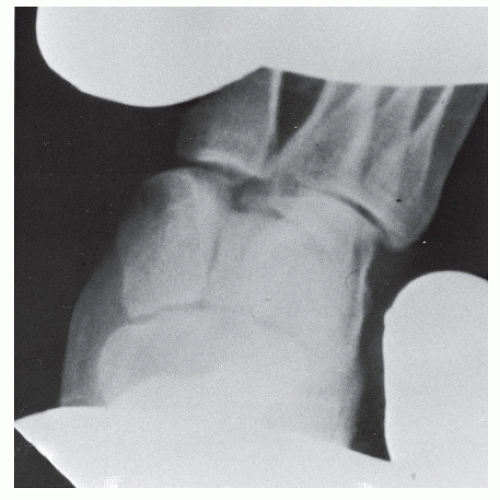

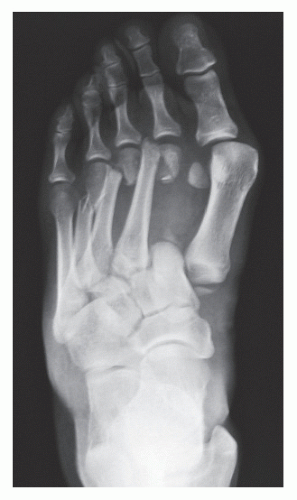

For those injuries grossly displaced, the diagnosis is rather straightforward (Fig. 116.5). However, subtle radiographic signs have to be recognized in those less obvious cases.

On the anteroposterior view, the metatarsal bases should line up with their corresponding cuneiforms and the cuboid. A gap greater than 2 mm between the medial and intermediate cuneiform may signify an injury. A “fleck fracture” or “fleck sign” may be evident at the medial base of the second metatarsal and is caused by traction of the Lisfranc ligament (Fig. 116.6A).

On the medial oblique view, the medial aspect of the fourth metatarsal aligns with the corresponding border of the cuboid (Fig. 116.6B).

The lateral view may depict a base of a metatarsal dorsally dislocated. Also, the arch height may be lowered (10,11 and 12) (Fig. 116.6C).

A practical rule to follow: When in doubt, obtain contralateral films. The intercuneiform gap may just be a normal variant when

compared with the other side when no other disruption is identified. This rule can be applied to any questionable pathology but seems to be utilized more in trauma cases. Probably the number one instance, however, is in pediatric cases comparing physes.

compared with the other side when no other disruption is identified. This rule can be applied to any questionable pathology but seems to be utilized more in trauma cases. Probably the number one instance, however, is in pediatric cases comparing physes.

TABLE 116.1 Lisfranc Classifications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

One can also see concomitant fractures on the radiographs, which can more readily lead to the Lisfranc fracture dislocation diagnosis. These other fractures are metatarsal fractures, digital fractures, and a cuboid fracture (12,13) (see Fig. 116.5).

The question often arises whether one should obtain a CT scan for a suspected Lisfranc injury (14,15 and 16). In those cases in which

the dislocation is obvious and not reduced upon presentation, a CT scan could be considered superfluous. When the injury is suspected but not readily identified on plain films, then a CT scan can be ordered (Fig. 116.7). Surgeon preference may dictate CT usage in both scenarios to ascertain the osseous integrity and degree of communition of the metatarsal bases for fixation or fusion. A CT scan may also demonstrate other subtle fractures of the midfoot. The author routinely orders CT scans for Lisfranc injuries. An MRI can also be ordered but rarely (17,18).

the dislocation is obvious and not reduced upon presentation, a CT scan could be considered superfluous. When the injury is suspected but not readily identified on plain films, then a CT scan can be ordered (Fig. 116.7). Surgeon preference may dictate CT usage in both scenarios to ascertain the osseous integrity and degree of communition of the metatarsal bases for fixation or fusion. A CT scan may also demonstrate other subtle fractures of the midfoot. The author routinely orders CT scans for Lisfranc injuries. An MRI can also be ordered but rarely (17,18).

Two other important concepts need to be addressed when dealing with a Lisfranc-type trauma.

These injuries may present open, which then initiates the Gustilo-Anderson open fracture classification and protocol (19).

The clinical presentation and mechanism of injury can lead to a compartment syndrome. The most important phrase “index of suspicion” then has to take hold and compartment pressures measured (20). Then two injuries are managed: the fracture dislocation (and other fractures if present) along with the compartment syndrome (Fig. 116.8). The latter is a surgical emergency.

Although it is academically sound to put each case into the proper classification, sometimes it is just impossible, especially if excessive disruption is evident, the injury is subtle, or spontaneous reduction has occurred.

TREATMENT

For a severely dislocated Lisfranc joint, some basic points need to be emphasized.

The neurovascular status has to be determined. Both will become integral parts of the workup to diagnose a

compartment syndrome. A salient question: is the foot pulseless because of the dislocation? If so, then the dislocation needs to be reduced to reestablish blood flow. Maneuvers for this could require the operating room, especially if an initial attempt fails. Keep the “attempts” to one, two at most. Too many can lead not only to damage of the soft tissues but osseous structures as well. Failure to establish blood flow necessitates immediate surgical intervention. Fasciotomies are performed for neurovascular compromise in the presence of a compartment syndrome.

compartment syndrome. A salient question: is the foot pulseless because of the dislocation? If so, then the dislocation needs to be reduced to reestablish blood flow. Maneuvers for this could require the operating room, especially if an initial attempt fails. Keep the “attempts” to one, two at most. Too many can lead not only to damage of the soft tissues but osseous structures as well. Failure to establish blood flow necessitates immediate surgical intervention. Fasciotomies are performed for neurovascular compromise in the presence of a compartment syndrome.

Any tenting of the skin by any dislocated position of bone is not appropriate. This can lead to local skin necrosis. Again, tenting needs to be addressed as soon as possible.

When the joint is not in anatomical alignment, but tenting does not exist, and there is no neurovascular compromise, one can then consider surgical intervention in an urgent though nonemergent fashion. As in other trauma, if a foot is in high tide in which the pinch test fails, and skin lines are absent, the surgery is postponed until low tide is established (21). At that time, pinching the skin will occur readily and skin lines will be evident. This should apply even in those cases in which percutaneous fixation is contemplated. Ice, compression, and elevation reduce edema. Therefore, surgery can wait until the soft tissue envelope is optimum. After 3 weeks, however, osseous healing is well underway and attempts at reduction and fixation will be difficult.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree