Chapter 17 Lesser-Toe Disorders

CHAPTER CONTENTS

The complaint of pain in the forefoot must be differentiated to make a correct diagnosis. The accompanying algorithm (Fig. 17-1) may prove useful in determining the specific forefoot diagnosis when a patient complains of metatarsalgia. Most important is the exact location of pain. In addition, the physician should ask the following questions: Which specific activities increase symptoms? Which activities alleviate discomfort? Is the pain dorsal or plantar, medial or lateral? Is there an associated neuritic symptom with the pain? Are enlarged exostoses or prominences associated with pain, swelling, or inflammation?

Bunionettes

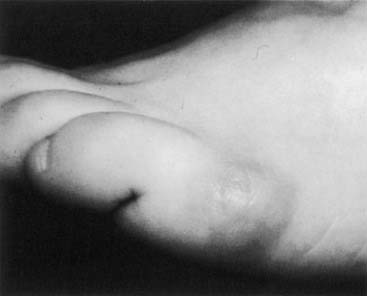

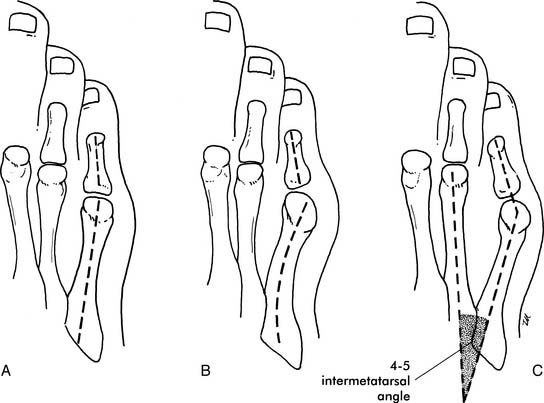

The development of inflammation, an enlarged bursa, or a callus over a prominent fifth metatarsal head may lead a physician to diagnose a bunionette (Fig. 17-2). Just as bunions can present with differing magnitude and different characteristics, so too can a bunionette.1 A bunionette may appear radiographically as an enlarged fifth metatarsal head (type I). A flare in the metaphysis may cause outbowing of the fifth metatarsal (type II), leading to symptoms, or a widened 4-5 intermetatarsal angle (type III) characteristic of a splayfoot may lead to pain and callus formation (Fig. 17-3).

Figure 17-2 Bunionette with enlarged bursa.

From Mann RA, Coughlin MJ: In Surgery of the foot and ankle, St Louis, 1993, CV Mosby, p. 443.

Conservative treatment

When athletic activity is significantly impaired after conservative efforts, surgical intervention may be contemplated (see Case Study 1). The type of osteotomy selected is dependent on the location of the callosity because specific osteotomies of the fifth metatarsal are oriented to redirect the metatarsal in different directions. Surgical intervention in treating forefoot callosities should be tailored to the patient. Extensive soft-tissue stripping, unsecured osteotomies, and multiple metatarsal osteotomies all should be avoided in athletes. Although a surgical procedure may relieve the painful callosity, athletic performance of the patient may be diminished and thus surgery may be considered unsuccessful. The two surgical procedures presented here fulfill the requirements of exposing the patient to less extensive surgery, use internal fixation, and appear better suited to athletes. Again, when possible, conservative treatment should be advocated by the treating physician until it obviously is incompatible with continued athletic function.

Case Study 1

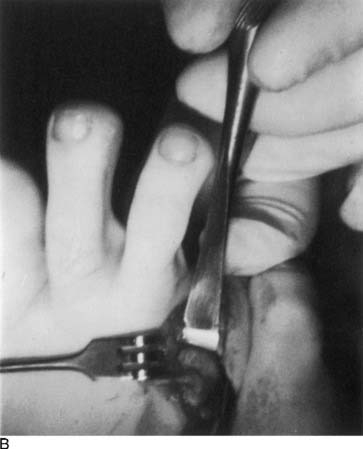

On physical examination, a normal neurologic and vascular examination was noted. Prominence of the fifth metatarsal head was characterized by a callosity on both the plantar and lateral aspect. Radiographic evaluation demonstrated an enlarged fifth metatarsal lateral condyle (Fig. 17-4, A).

Conservative care, stretching of shoes, and padding all were recommended.

At the end of ski season, the patient requested surgical treatment because of continued symptoms. An oblique osteotomy was performed and fixed with screws. At 8 weeks following surgery, the osteotomy was healed and the patient began progressive walking that evolved over the ensuing 2 months to jogging and sports activities. Figure 17-4, B shows the correction obtained. The patient skied the following season without symptoms.

Surgical Treatment

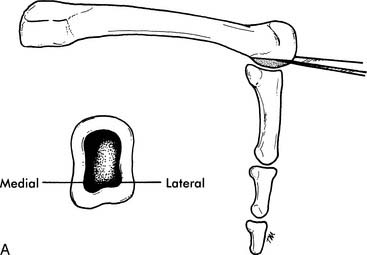

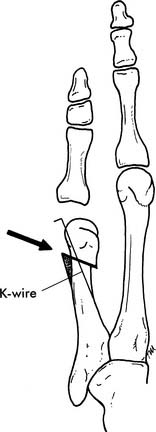

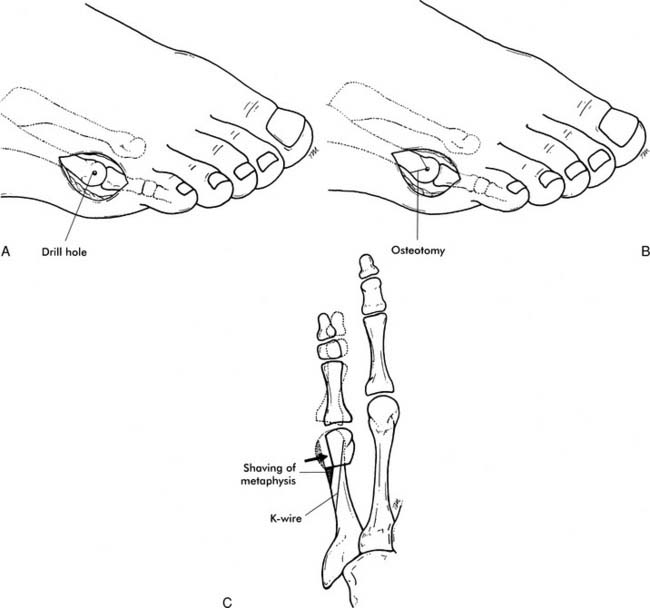

Figure 17-7 Distal oblique osteotomy with K-wire fixation (shaded area denotes shaved bone in metaphysic).

In general, resolution of the symptomatic bunionette can be achieved with one of the above procedures for type I or type II bunionettes. With a splayfoot and a significantly wide 4-5 metatarsal angle, a diaphyseal midshaft osteotomy may be necessary to achieve more correction.6 More extensive procedures such as this should be reserved for athletes with significant limitations, because the extensive nature of this surgery may limit postoperative athletic expectations.

Intractable Plantar Keratoses

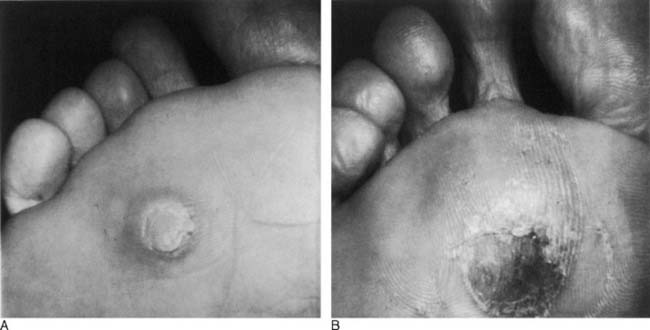

The development of a keratosis beneath one or more of the metatarsal heads is referred to as an intractable plantar keratosis or IPK. A callosity beneath the fifth metatarsal when associated with a bunionette already has been discussed. A callus may be a localized discrete lesion or a diffuse keratotic buildup (Fig. 17-9). Callus formation in athletes is not uncommon, and if asymptomatic rarely requires medical intervention. With significant buildup, painful symptoms may occur, requiring evaluation and treatment.

Figure 17-9 (A) Discrete callus in a tennis player with an enlarged fibular condyle. (B) Diffuse callus in a runner.

Courtesy Roger A. Mann, MD, and Michael J. Coughlin, MD.

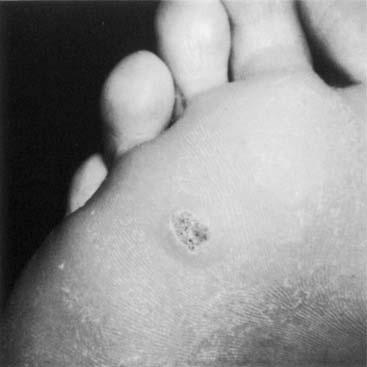

A diffuse callus may be due to repetitive abrasion associated with athletic activity. It also may be associated with a long second metatarsal or a long second and third metatarsal. A discrete callus may occur beneath a single metatarsal head.7 It typically is associated with an enlarged fibular metatarsal condyle. It is important to distinguish this from a wart (Fig. 17-10). Although warts (plantar verrucae) typically are not found beneath a metatarsal head, on occasion they can occur in this region and thus must be differentiated from an IPK. Trimming of a wart will uncover end arterioles in the lesion characterized by punctuate hemorrhages. Evaluation of the athlete with an IPK involves determining the significance of the symptoms, length of duration, and association, if any, with specific athletic activity. A patient with minimal symptoms requires no treatment.

Figure 17-10 A wart is characterized by punctate hemorrhages that are obvious when the callus is trimmed.

Courtesy Roger A. Mann, MD, and Michael J. Coughlin, MD.

Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment revolves around paring the IPK and padding it to relieve the pressure (Fig. 17-11). A patient can be instructed to trim the lesion every 7 to 10 days, and this will significantly relieve discomfort. Placement of a metatarsal pad just proximal to the IPK can transfer pressure to the metatarsal diaphysis and relieve symptoms (see Case Study 2). Custom or prefabricated orthotic devices also can aid in relieving symptoms. Athletes may alter their workout, change sporting activities, or change duration or intensity of the workout, all with gratifying results.

Surgical Treatment: Partial Condylectomy8

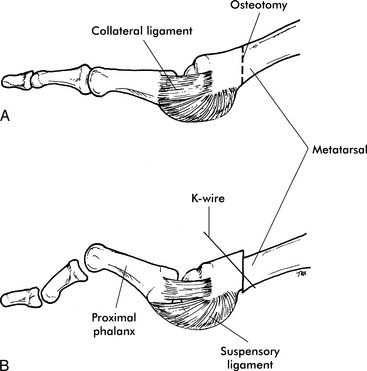

Surgical Treatment: Metatarsal Osteotomy

Figure 17-14 Distal chevron osteotomy with internal fixation.

Courtesy Roger A. Mann, MD, and Michael J. Coughlin, MD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pearl

Pearl Pearl

Pearl

Pearl

Pearl