Latissimus Dorsi Tendon Transfer

John G. Costouros MD

Christian Gerber MD

Jon J. P. Warner MD

Irreparable tendon tears of the rotator cuff are found in a small proportion of patients with rotator cuff tears as approximately 95% of all tears are reparable by conventional methods at the time of surgery.1 Although the prevalence of irreparable tendon tears is quite low, they profoundly impact the functional capacity of patients and can be associated with significant levels of pain. Tendon transfer techniques, including the latissimus dorsi tendon transfer, have been developed in order to improve pain and function in selected patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears.

Massive, irreparable tears are defined as tears involving at least two rotator cuff tendons with retraction that is not amenable to mobilization and repair to the anatomical footprint with the arm in less than 60 degrees of abduction.2 Recent advances have enabled the surgeon to preoperatively determine whether or not a large rotator cuff tear is amenable to primary repair or, if it is technically reparable, whether or not it will be associated with a good functional outcome.3 This is based on both clinical and radiographic findings that are made prior to surgery.

Posterosuperior rotator cuff tears are the most common type of configuration of massive rotator cuff tendon tears. These involve the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and, less commonly, the teres minor. The latissimus dorsi transfer offers a reasonable solution to patients with significant pain and dysfunction associated with a massive, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears.

History of the Technique

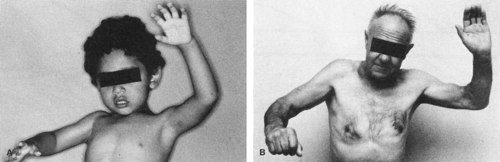

Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer was first described in 1988 by Christian Gerber for the management of irreparable, massive, posterosuperior rotator cuff tendon tears.2 The use of the latissimus dorsi has been well described in the treatment of brachial plexus birth palsy, in which patients display a similar functional deficit4,5,6,7 (Fig. 8-1A,B). Active external rotation of the adducted and abducted arm is lost, which severely impairs the ability of the patient to position the arm in space. Thus, the glenohumeral joint must compensate by generating much more flexion and abduction to reach the same height.2

In the treatment of brachial plexus birth palsy, variations in technique have shared the same goal of converting the teres major and latissimus dorsi to external rotators of the shoulder.4,5,6,7 Since 1934, when L’Episcopo5 first described his surgical procedure, this has proven to be an effective form of treatment. For this reason, it was seen that massive rotator cuff tears constituted an analogous problem of the adult that might be amenable to a similar treatment. Latissimus dorsi transfer was conceived as a method to provide containment of the humeral head in the setting of a massive, irreparable rotator cuff tear with the additional benefit of external rotation force. In this way, a fixed fulcrum of rotation would increase the efficiency of the remaining rotator cuff muscles and the deltoid in order to generate improved motion.2,8,9

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for tendon transfer have been established based on a number of clinical studies and observations2,9,10 (Table 8-1). In general, this procedure is indicated in individuals who have refractory pain, weakness, and dysfunction of the shoulder in the setting of an irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tear. Good subscapularis and deltoid function as well as minimal evidence of osteoarthritis are prerequisites prior to considering this procedure (Figs. 8-2A,B,C,D,E,F, 8-3).

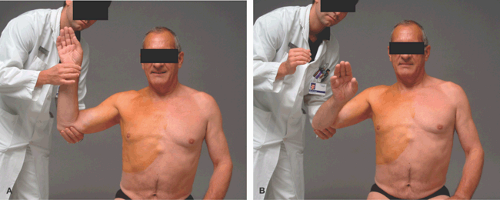

Patients with an irreparable posterosuperior tear will have a lag between passive and active external rotation. In these cases, the patient’s arm will fall into internal rotation when the examiner releases it from maximal passive external rotation (Fig. 8-4A,B). When the arm is at the side in adduction, this degree of lag is consistent with an irreparable tear of the infraspinatus (Fig. 8-5A,B). When the patient’s arm is abducted and held in maximal passive external rotation position, the patient may be able to actively maintain this position if the teres minor is intact.

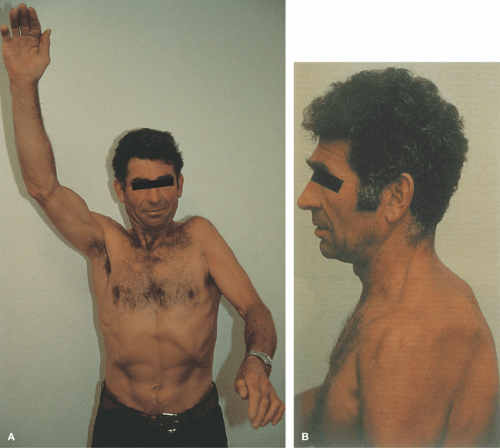

The degree of weakness is important in the clinical decision making and in determining whether this tendon transfer is an appropriate method of treatment. If the patient has mild to moderate weakness, then a latissimus transfer can be expected to give sufficient force to elevate the arm against gravity above shoulder level. We determine this by assisting the patient in raising the arm. If the degree of assistance required to raise the arm overhead is minimal, then a latissimus transfer is indicated. If, however, the patient requires a great deal of assistance to raise the arm and when the examiner releases the arm the patient cannot maintain it overhead, then a latissimus transfer is not likely to effectively restore the patient’s ability to raise the arm overhead. We describe this patient as having a pseudoparalysis (Fig. 8-6A,B).

Table 8-1 Surgical Indications for Latissimus Dorsi Transfer in Posterosuperior Defects | |

|---|---|

|

Contraindications to latissimus dorsi tendon transfer include associated anterosuperior tears that involve the subscapularis, cases of static anterior or posterior subluxation, advanced arthritis, axillary nerve injury, or infection. Of course, all considerations for treatment must be catered to an individual patient’s disability and expectations for pain relief and functional recovery. Comorbid conditions including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, uncontrolled seizure disorder, or immunosuppression may have a negative impact on the patient’s potential for recovery and ability to adhere to a rigorous postoperative rehabilitation regimen.

Weakness of the subscapularis and deltoid are clinically assessed by the lift-off and extension lag signs, respectively11,12 (Fig. 8-7A,B,C,D). Dynamic anterosuperior subluxation can be elicited by asking the patient to actively abduct the arm and indicates deficiency of the subscapularis (Fig. 8-8A,B). If these clinical signs are present, latissimus dorsi tendon transfer should not be performed.

Radiographic evaluation in all patients consists of a true anteroposterior plain radiograph with the arm in neutral rotation. This enables the assessment of the acromiohumeral distance (Fig. 8-9A,B). An acromiohumeral distance of 5 mm or less is a relative contraindication to performing the latissimus transfer. Cranial migration of the humerus perpetuates subacromial impingement and reduces the efficiency of the deltoid muscle as an abductor. The axillary lateral radiograph allows one to determine the presence of static anterior and posterior subluxation and the stage of glenohumeral arthritis (Fig. 8-9A,B). Further imaging includes either a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with intra-articular contrast. MRI is the currently preferred

method for assessment of tear quality and size, degree of retraction, and degree of fatty degeneration and muscle atrophy13,14 (Fig. 8-10A,B). Massive tears of Goutallier stage III or greater suggest an irreparable tear with poor-quality tissue likely to be encountered at the time of surgery.3

method for assessment of tear quality and size, degree of retraction, and degree of fatty degeneration and muscle atrophy13,14 (Fig. 8-10A,B). Massive tears of Goutallier stage III or greater suggest an irreparable tear with poor-quality tissue likely to be encountered at the time of surgery.3

Surgical Techniques

Dr. Gerber’s Technique in Beach Chair

Surgery is performed under general anesthesia combined with patient-controlled interscalene analgesia (PCIA), which facilitates early passive mobilization postoperatively. The patient is placed in a beach-chair position in such a manner that sufficient access to the entire scapula and latissimus dorsi muscle belly is possible using a full-length bean bag. A mechanical arm holder is not used during the operation.

The bony landmarks of the shoulder are palpated and outlined, including the acromion, acromioclavicular joint, coracoid process, and clavicle. An anterosuperior approach to the rotator cuff is performed through a 12-cm incision parallel to the Langer lines over the lateral one third of the acromion (Fig. 8-11A). In general, this incision begins at the posterolateral edge of the acromion and ends anteriorly 2 to

3 cm lateral to the coracoid process. The anterolateral deltoid is detached from its origin with a thin wafer of bone using a flexible half-inch osteotome in order to allow for preferential bone-to-bone healing following repair of the deltoid at the completion of the procedure (Fig. 8-11B,C,D). The deltoid is split no more than 5 cm from its origin at the junction of the anterior and middle raphe in order to avoid possible injury to the axillary nerve.

3 cm lateral to the coracoid process. The anterolateral deltoid is detached from its origin with a thin wafer of bone using a flexible half-inch osteotome in order to allow for preferential bone-to-bone healing following repair of the deltoid at the completion of the procedure (Fig. 8-11B,C,D). The deltoid is split no more than 5 cm from its origin at the junction of the anterior and middle raphe in order to avoid possible injury to the axillary nerve.

The subacromial bursa is resected sharply, and minimal anterior acromioplasty is performed as well as distal clavicle resection if needed. A subacromial retractor (Sulzer Medica, Winterthur, Switzerland) (Fig. 8-12) is placed in order to allow visualization of the entire rotator cuff, from the teres minor to the subscapularis. The long head of the biceps is routinely tenodesed into the bicipital groove using a nonabsorbable anchor, as there is frequently degeneration in the setting of a massive tear and may persist as a significant pain generator following surgery.

Mobilization of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons is then performed, beginning on the bursal surface and proceeding to the articular surface, followed by placement of traction sutures using nonabsorbable, braided suture (no. 2 Ethibond, Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Westwood, Mass) in a modified Mason-Allen configuration (Fig. 8-13). Mobilization may include

release of the coracohumeral ligament, interval slide, and circumferential capsulotomy. Release of the articular side of the posterosuperior cuff does not extend beyond 1.5 cm medial to the glenoid rim in order to avoid inadvertent injury to the suprascapular nerve.15

release of the coracohumeral ligament, interval slide, and circumferential capsulotomy. Release of the articular side of the posterosuperior cuff does not extend beyond 1.5 cm medial to the glenoid rim in order to avoid inadvertent injury to the suprascapular nerve.15

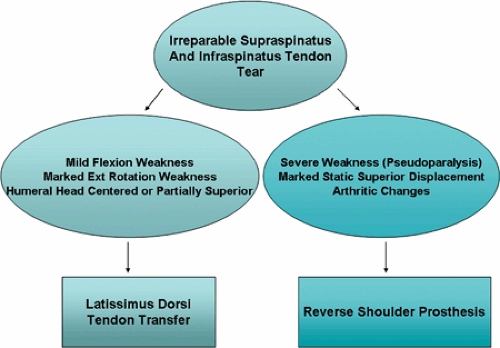

Fig. 8-3. Treatment algorithm for patients with irreparable tears of the posterosuperior rotator cuff. |

Fig. 8-5. With the arm in adduction, a lag between maximal passive and active external rotation (A,B) is pathognomonic of a tear of the infraspinatus. |

Fig. 8-6. A 52-year-old mason with a traumatic posterosuperior rotator cuff injury. At examination, he showed (A) the inability to raise the arm against gravity, or pseudoparalysis, with (B) clinical evidence of severe atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. (Reprinted with permission from Gerber C. Massive rotator cuff tears. In: Iannotti JP, Williams GR, eds. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:60.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|