Lateral Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction

Shawn W. O’Driscoll MD, PhD

History of the Technique

Recurrent instability of the elbow almost always occurs via a mechanism of displacement referred to as posterolateral rotatory instability.1 Posterolateral rotatory instability is a kinematic phenomenon. Therefore, the term can be used to describe both acute and recurrent instability and even chronic instability. It represents a spectrum, as do many other joint instabilities, and can present from mild or even subclinical subluxation, all the way through to profound instability. Also, as with other joint instabilities, it can present in association with other fractures, most commonly the coronoid and radial head.

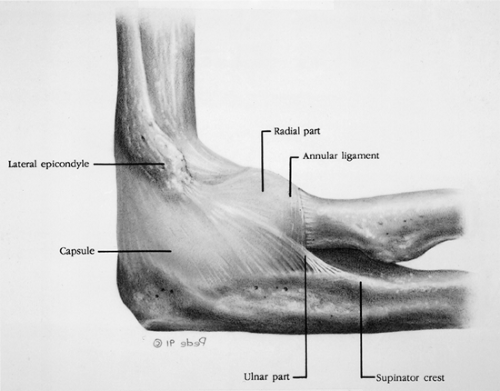

An understanding of elbow instability is predicated on knowledge of the anatomy of the lateral collateral ligament complex and of the mechanism and kinematics of elbow subluxation and dislocation. The lateral collateral ligament complex is the key structure involved in recurrent elbow instability, and it is virtually always disrupted in elbow dislocations that result from a fall. The ulnar part of the lateral collateral ligament complex (also known as lateral ulnar collateral ligament) is the critical portion of the ligament complex, securing the ulna to the humerus and preventing posterolateral rotatory instability2,2 (Fig. 31-1).

Elbow dislocations or subluxations typically occur as a result of falls on the outstretched hand.1,3 This produces a combination of supination or external rotation torque, along with valgus and axial compression during flexion, which causes the elbow to subluxate or dislocate (Fig. 31-2A). The pathoanatomy can be thought of as a circle of soft tissue or bone disruption from lateral to medial in three stages (Fig. 31-2B). In stage 1 the lateral collateral ligament is partially or completely disrupted (the ulnar part is disrupted). This results in posterolateral rotatory subluxation of the elbow, which reduces spontaneously (Fig. 31-2A). With further disruption anteriorly and posteriorly, the elbow in stage 2 instability is capable of an incomplete posterolateral dislocation in which the concave medial edge of the ulna rests on the trochlea. In this situation the lateral x-ray gives one the impression of the coronoid being perched on the trochlea. This can readily be reduced with minimal force or by the patient manipulating the elbow him- or herself. Stage 3 is subdivided into three parts. In stage 3A all the soft tissues are disrupted around to and including the posterior part of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), leaving the important anterior band intact. During valgus testing, the intact anterior medial collateral ligament (AMCL), provides valgus stability provided that the elbow is kept in pronation to prevent posterolateral rotatory subluxation. This stage of instability is most commonly seen in the presence of radial head and coronoid fractures. In stage 3B the entire medial collateral complex is disrupted. Varus, valgus, and rotatory instability is present following reduction. In stage 3C the entire distal humerus is stripped of soft tissues. This produces severe instability such that the elbow will dislocate or subluxate even in a cast at 90 degrees of flexion. Reduction can be maintained usually only by flexing the elbow past 90 to 110 degrees. The flexor/pronator muscle origin, which is an important secondary stabilizer of the elbow, is disrupted in stage 3C. These pathoanatomic stages all correlate with clinical degrees of elbow instability.

Most commonly, elbow dislocations involve disruption of both the medial and lateral collateral ligaments.4,5,6 This circle of disruption is referred to as the Horii circle and is analogous to the Mayfield spiral of soft tissue or bony disruption in carpal instability (Fig. 31-2B). As disruption progresses from lateral to medial it may pass through the soft tissues or bone (i.e., the capsule is normally torn but may be intact if the coronoid is fractured). Similarly, the anterior bundle of the MCL is often intact when the radial head and coronoid are both fractured.

This explains the spectrum of instability, which progresses from posterolateral rotatory instability, to perched

dislocation, to posterior dislocation without disruption of the AMCL, to posterior dislocation with disruption of the AMCL (and eventually the common flexor/pronator origin) that occurs with further posterior displacement. Such a posterolateral rotatory mechanism for dislocation would be compatible with those suggested in the 1960s by Osborne and Cotterill7 and Roberts.8

dislocation, to posterior dislocation without disruption of the AMCL, to posterior dislocation with disruption of the AMCL (and eventually the common flexor/pronator origin) that occurs with further posterior displacement. Such a posterolateral rotatory mechanism for dislocation would be compatible with those suggested in the 1960s by Osborne and Cotterill7 and Roberts.8

Recurrent posterolateral rotatory instability usually is posttraumatic due to inadequate soft tissue healing following an elbow subluxation, dislocation, or fracture-dislocation. It can be iatrogenic9 and is caused by violation of the lateral collateral ligament complex during release for tennis elbow. It can also result from chronic soft tissue overload in patients with long-standing cubitus varus deformity from childhood supracondylar malunions.10 It may also be seen in patients who bear weight on the upper extremities (paralysis due to polio, paraplegia) and in those with connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow has also been seen following multiple injections for lateral epicondylitis. It is one of the differential diagnoses that should be considered in patients presenting with apparent tennis elbow.

Recurrent instability of the elbow, once enigmatic, is now understood to involve a common pathway of posterolateral rotatory subluxation. In virtually all cases the ulnar part of the lateral collateral ligament is detached or attenuated. The medial collateral ligament is usually intact. Even when the medial collateral ligament is also disrupted, it is usually the lateral ligament that does not heal, probably because of gravitational varus stress.

Recurrent instability has caused great confusion for years but has recently become better understood. It is probably more common than previously thought, and indeed two long-term series reported symptoms of recurrent instability in 15% and 35% of their patients respectively, though they could not usually demonstrate the instability on examination.11,12 (These exams were performed prior to publication of the concept of posterolateral rotatory instability.)

Posterolateral rotatory instability is being diagnosed with increasing frequency since its discovery, probably due to increased awareness of the condition. Patients typically present with a history of recurrent painful clicking, snapping, clunking, or locking of the elbow and careful interrogation reveals that this occurs in the extension half of the arc with the forearm in supination. A preceding history of trauma or surgery is usually present unless there is a connective tissue disorder or chronic stretching due to crutch walking. The typical cause is a previous dislocation but can be as subtle as a sprain, resulting from a

fall on the outstretched hand. Surgical causes include radial head excision and lateral release for tennis elbow (due to violation of the ulnar part of the lateral collateral ligament).

fall on the outstretched hand. Surgical causes include radial head excision and lateral release for tennis elbow (due to violation of the ulnar part of the lateral collateral ligament).

Fig. 31-2. A: Elbow instability is a spectrum from subluxation to dislocation. The three stages illustrated here correspond with the pathoanatomic stages of capsuloligamentous disruption in Figure 31-1B. Forces and moments responsible for displacements are illustrated. (Reprinted with permission from O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF, Korinek S, et al. Elbow subluxation and dislocation. Clin Orthop. 1992;280:195.) B: The Horii circle soft tissue injury progresses in a circle from lateral to medial in three stages correlating with those in Figure 31-1A. In stage 1, the ulnar part of the lateral collateral ligament, the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL), is disrupted. In stage 2 the other lateral ligamentous structures and the anterior and posterior capsule are disrupted. Stage 3, disruption of the medial ulnar collateral ligament (MUCL) can be partial with disruption of the posterior MUCL only (stage 3A), or complete (stage 3B). The common extensor and flexor origins are often disrupted as well. (Reprinted with permission from O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF, Korinek S, et al. Elbow subluxation and dislocation. Clin Orthop. 1992;280: 194.) |

The physical examination may seem unremarkable except for a positive lateral pivot shift apprehension test (posterolateral rotatory apprehension test)9 (Fig. 31-3A). With the patient in the supine position and the affected extremity overhead, the wrist and elbow are grasped as though one might think of holding the ankle and knee when examining the leg (Fig. 31-3B). The elbow is supinated with a mild force at the wrist and a valgus moment is applied to the elbow during flexion (Fig. 31-3C). This results in a typical apprehension response with reproduction of the patient’s symptoms and a sense that the elbow is about to dislocate. Reproducing the actual subluxation and the clunk that occurs with reduction can usually only be accomplished with the patient under general anesthetic or occasionally after injecting local anesthetic into the elbow joint. The lateral pivot shift test performed in that manner results in subluxation of the radius and ulna off the humerus, which causes a prominence posterolaterally over the radial head and a dimple between the radial head and the capitellum (Fig. 31-3D). As the elbow is flexed to approximately 40 degrees or more, reduction of the ulna and radius together on the humerus occurs suddenly with a palpable visible clunk. It is the reduction that is apparent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree