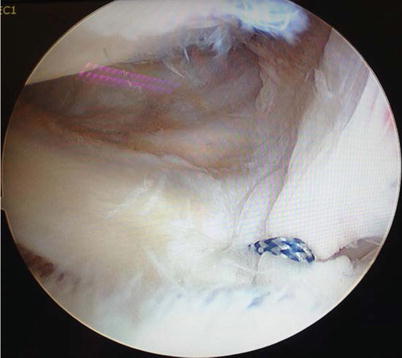

Fig. 38.1

Lateral meniscal root tear (MRI sagittal view)

Stoller et al. [35] proposed an MRI classification of meniscal tears based on signal intensity and extension of the articular surface (see Table 38.1).

Grade | Pattern |

|---|---|

Grade 0 | Normal homogeneous low signal intensity |

Grade 1 | Nonarticular focal or globular intrasubstance increased signal |

Grade 2 | Linear intrasubstance increased signal, which does not involve articular meniscal surface |

Grade 3 | Increased signal intensity communicating at least with one articular meniscal surface |

A complete discoid meniscus can be easily recognized on MR images because of its disk-like configuration. On the other hand, the recognition of an incomplete discoid meniscus may be more difficult. Typically, it involves only the posterior or anterior horn of the meniscus, and a trapezoidal appearance is seen.

A linear-increased signal communicating with the articular surface of a discoid meniscus is highly suggestive of meniscal tear.

38.4 Therapeutic Approach

The increased knowledge of the anatomical and functional importance of the menisci has radically modified the therapeutic approach to meniscal lesions.

Time has long passed since McMurray affirmed “a common error is the incomplete removal of the injured meniscus.” This was based on the theory that the residual meniscus had a role in promoting the progression of knee arthropathy [36].

The modern approach to meniscal injuries in athletes and active patients is based on studies that have extensively demonstrated the negative impact that meniscectomy has on the articular cartilage, in particular in the lateral side of the knee. In a study with a 13-year follow-up, a 40 % reduction in the lateral joint line was seen after meniscectomy, while it was 28 % for the medial joint line [37]. This is related to the different anatomy and joint congruence between the lateral and the medial side of the knee.

Studies on biomechanical changes arising in the knees after a meniscectomy show that there is a 235 % increase of loads on the articular cartilage in the lateral side and 75 % in the medial side, with consequent biochemical and structural modifications in the cartilage tissue [38]. A published study reported that at a 30-year follow-up, 80 % of subjects who had undergone a total medial meniscectomy were satisfied with the outcomes of the procedure versus 47 % of subjects who had undergone a lateral meniscectomy [39].

Athletes are statistically more at risk to develop degenerative changes following meniscal lesions and consequent meniscectomy. The incidence of arthritis after meniscectomy is 15 % in professional soccer players versus 4 % in nonprofessional, while this rate is only 1.6 % in individuals who do not participate in sports. X-rays show signs of early arthritis already after 4.5 years. Arthritic changes are more evident after 14.5 years in 89 % of the athletes, with 46 % of them abandoning competitions due to pain [40–42]. Poor outcomes after meniscectomy are seen especially in professional volleyball players [43].

Therefore, based on the evidence available in the international literature, the surgical treatment of meniscal lesions in athletes has become less radical. Meniscal repair with the different suture techniques available is an option and is always taken into consideration in order to preserve meniscal function and prevent the degeneration of cartilage surfaces. However, when a meniscal repair is preferred, surgeons, athletes, and staff together should consider two fundamental aspects: the variable time frames in the rehabilitation program/return to sport after the repair and the possibility of the failure of the repair with the risk of a second surgery.

The indication to treat a meniscal tear is based primarily on the patient history and physical examination. A torn meniscus that does not show a clinical pattern of pain and functional limitation may be treated conservatively. This decision is supported by the proven capacity of spontaneous healing in some types of meniscal lesions in the red-red zones (noncomplex longitudinal or vertical tears) [6, 44–46].

When dealing with a symptomatic traumatic LM tear in an athlete, the surgical treatment is indicated (Fig. 38.2). Acute LM lesions in the red-red or red-white zones may be treated with all-inside, inside-out, outside-in meniscal sutures, in relation to the morphology and site of the lesion. A meniscal suture is performed for a recent lesion in the red zone, in a stable knee, or when associated to an ACL reconstruction in a young and active individual. In the last decades, tissue-engineering approaches have been advocated to improve the reparative process. The use of growth factors seems in facts able to improve the meniscal healing [47, 48]; nevertheless, further studies are needed to evaluate the potential for clinical application.

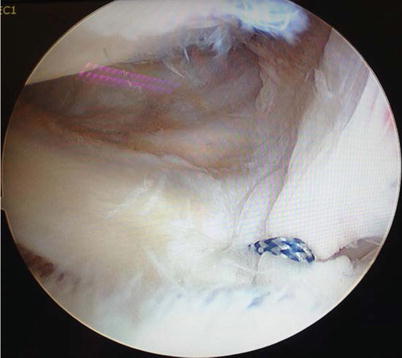

Fig. 38.2

Lateral meniscal root pull-out suture repair

Meniscal sutures, however, impose some postoperative restrictions that have to be accepted and respected by the athlete and the staff in order to reduce the risk of failure. In absence of a complete understanding and approval by the athlete and the team of the recovery time foreseen after surgery, the meniscal repair of the MM should not be taken into consideration; therefore, the only surgical option would be a meniscectomy.

In literature, the percentage of failures for meniscal repair ranges between 5 and 43 % (mean 15 %). Failures for MM repairs are statistically higher than those reported for the LM [49].

Several medium- and long-term follow-up studies analyzing the comparative results between partial meniscectomy and meniscal repair for traumatic lesions in athletes show that 96 % of the athletes who underwent a meniscal repair return to pre-injury activity level compared to 50 % of athletes who underwent meniscectomy [50].

In 2011, Paxton et al. published a literature review analyzing the long- and short-term outcomes of partial meniscectomy versus meniscal repair for acute meniscal tears. In the long term, 3.7 % of patients who had undergone partial meniscectomy had to undergo a second surgery; the incidence was greater for LM lesions compared to medial lesions. On the other side, the percentage of meniscal repair failures was 20.7 % with a higher rate reported for the MM compared to the LM. The long-term outcomes, in terms of functional recovery and x-ray findings, were better in individuals who underwent meniscal repair [51].

In selected cases, when athletes develop a “post-meniscectomy syndrome” secondary to a previous subtotal meniscectomy, a meniscal transplant with allograft (MAT: meniscus allograft transplantation) would be indicated with the aim to improve patients’ symptoms and quality of life and prevent arthritis. A study by Cugat et al. analyzing the outcome of this procedure in 15 professional soccer players reported that 14 out of the 15 athletes were able to return to sports at a 36-month follow-up [52].

38.5 Conclusions

Based on the evidence from the available international literature, the treatment of meniscal lesions in athletes should be aimed to the preservation of the LM, favoring meniscal repair techniques. This would lead to a decreased risk of cartilage degeneration and progression toward osteoarthritis. On the other hand, it has also been shown that this approach ensures higher sport performance in the long term.

However, the athletes and the teams should be carefully informed and should understand that the meniscal repair is associated with a longer recovery time compared to a meniscectomy. Moreover, they should be aware of the possibility of a second surgery in the case of failure of the repair or if meniscal healing does not occur.

References

1.

Clark CR, Ogden JA (1983) Development of the menisci of the human knee joint. Morphological changes and their potential role in childhood meniscal injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 65:538–547PubMed

2.

Gardner E, O’Rahilly R (1968) The early development of the knee joint in staged human embryos. J Anat 102:289–299PubMedCentralPubMed

3.

Greis PE, Bardana DD, Holmstrom MC, Burks RT (2002) Meniscal injury: I. Basic science and evaluation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 10:168–176PubMed

4.

Aydingoz U, Kaya A, Atay OA et al (2002) MR imaging of the anterior intermeniscal ligament: classification according to insertion sites. Eur Radiol 12(4):824–829CrossRefPubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree