CHAPTER 3 Lateral Epicondylitis: Débridement, Repair, and Associated Pathology

Lateral humeral epicondylitis was first described in the German literature by Runge in 1873.1 Ten years later, Morris reported an association between lateral epicondylitis and lawn tennis, leading to its common designation as tennis elbow.2 Since these original descriptions were published, multiple causes and various treatments for this condition have been proposed.

Despite advances in our understanding of the pathoanatomy of lateral epicondylitis, controversy remains regarding its optimal nonoperative and operative management. Most patients respond successfully to a variety of conservative methods. In the studies reported by Boyd and McLeod,3 Coonrad and Hooper,4 and Nirschl and Pettrone,5 4% to 11% of patients ultimately required operative intervention for recalcitrant symptoms. Many different operative procedures have been described in the orthopedic literature: percutaneous,6–11 endoscopic,12,13 and myriad open techniques, such as excision of abnormal degenerative tissue with simple suture repair4,5,7,10,14-17 or formal repair of the extensor tendons back to the lateral epicondyle.18–20 Clinical outcomes of arthroscopic treatment have been reported.10,16,21–29 In one study, we found high rates of clinical success for our patients with lateral epicondylitis treated arthroscopically using the technique described in this chapter.21,22

ANATOMY

Nirschl and associates detailed the most commonly accepted theory of the pathogenesis of lateral epicondylitis.5,30 Building on the previous findings of Cyriax,31 Goldie,32 and Coonrad and Hooper,4 Nirschl observed that the basic underlying lesion was in the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) tendon. Repetitive overuse leads to microtears in the ECRB origin. Tendinous nonrepair and replacement with immature reparative tissue often follow. Histopathologic examination revealed an absence of inflammatory cells and the presence of a degenerative process, with tissue first characterized as angiofibroblastic hyperplasia and later modified to angiofibroblastic tendinosis.5,30,33,34

In a cadaveric study, Cohen and associates35 characterized the ECRB origin as diamond shaped and as beginning just anterior to the most distal aspect of the lateral supracondylar ridge. The anatomic ECRB footprint is located between the most proximal aspect of the capitellum and the midline of the radiocapitellar joint (Fig. 3-1). The lateral collateral ligamentous complex, consisting of the radial collateral ligament, annular ligament, accessory collateral ligament, and lateral ulnar collateral ligament, lies posterior to the ECRB origin. This lateral collateral ligamentous complex is not disrupted during arthroscopy as long as resection of the ECRB and elbow capsule is kept anterior to a line bisecting the radial head.36

PATIENT EVALUATION

Diagnostic Imaging

Lateral epicondylitis is a clinical diagnosis. We routinely obtain plain anteroposterior, lateral, and axial radiographic views of the elbow as part of the initial evaluation in the patient presenting with elbow pain. Although they are frequently normal, the radiographs may show radiocapitellar arthrosis, which should be included in the differential diagnosis. Plain radiographs may show soft tissue calcification adjacent to the lateral epicondyle in approximately 25% of patients, especially if the patient previously had steroid injections. Although unnecessary for the diagnosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide additional information regarding suspected intra-articular pathology, the integrity of the lateral collateral ligamentous complex, and the presence and extent of extensor tendon tearing.37

TREATMENT

Conservative Management

Many nonoperative treatments have been reported. A regimen that includes activity modification, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, counterforce bracing, and corticosteroid injections is usually successful in reducing symptoms and allowing a progressive return to unrestricted activities. Novel approaches include injections of buffered platelet-rich plasma38 or botulinum toxin39 and application of extracorporeal shock wave therapy.40

Arthroscopic Technique

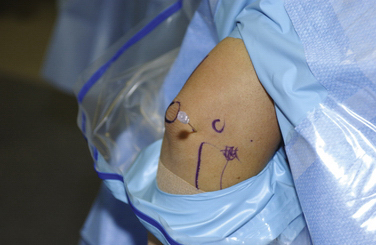

For the arthroscopic procedure, the patient can be placed in the supine, lateral decubitus, or prone position. We prefer the prone position with the use of a general anesthesia to allow accurate postoperative neurovascular assessment. A well-padded tourniquet is applied to the upper arm, which is then placed into a commercially available arm holder (Fig. 3-2). The extremity is then prepared and draped in standard fashion. A compressive dressing is wrapped around the forearm to help prevent leakage of fluid into the distal soft tissues. Several bony anatomic landmarks and important structures are outlined with a marking pen to assist in proper portal creation: medial and lateral epicondyles, radial head, olecranon tip, and ulnar nerve (Fig. 3-3).

The limb is exsanguinated, and the tourniquet is inflated to 250 mm Hg. An 18-gauge spinal needle is introduced into the lateral soft spot, which can be found in the center of a triangle formed by the palpable radial head, lateral epicondyle, and olecranon. The joint is injected with approximately 20 to 30 mL of saline (Fig. 3-4). Joint distention pushes the neurovascular structures more anterior, thereby protecting them from iatrogenic injury.