Lateral Column Lengthening with Medial Column Stabilization for Adult Acquired Flatfoot

Brian C. Toolan

Lengthening the lateral column of the foot offers an effective means by which to correct a pes planovalgus deformity (1, 2, 3 and 4). Evans believed the lateral column was the foundation of pedal structure and the length of the lateral column relative to the medial column was the principal determinant of pedal alignment (5). His experience with osteotomy through the anterior process of the calcaneus and interposition of an iliac crest bone graft introduced lateral column lengthening for the operative management of flatfoot in children.

The successful treatment of pediatric pes planovalgus with this procedure leads to its application for adult deformity (6,7). Hansen corrected adult acquired flatfoot deformity (AAFD) secondary to posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) by lengthening the lateral column through distraction arthrodesis of the calcaneocuboid joint combined with realignment and stabilization of the medial column (3,8). Arthrodesis of the naviculocuneiform, first tarsometatarsal, or both was included in the reconstruction when significant “sag” caused by dorsiflexion, dorsal translation, or gapping of these joints indicated medial column instability was present. Subsequently, numerous surgeons reported excellent functional and radiographic results after reconstructing an adult flatfoot by lengthening the lateral column (1, 2, 3 and 4,8, 9 and 10).

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications are AAFDs associated with:

Dysfunction, rupture, or injury of the posterior tibial tendon causing a flexible pes planovalgus deformity; Stage II PTTD (11, 12, 13 and 14)

Rheumatoid arthritis without appreciable inflammatory arthritis of the talonavicular or subtalar joint

Peroneal spasticity arising from childhood

Talocalcaneal or calcaneonavicular coalition combined with or after resection of the coalition

Painful accessory navicular and attenuated function of the posterior tibial tendon or after failed Kidner procedure

Shortening of the lateral column due to a traumatic injury of the midfoot, impaction-compression fracture of the cuboid or anterior process of the calcaneus, and/or disruption of the calcaneocuboid joint

Primary osteoarthritis of the calcaneocuboid joint and a short lateral column

Salvage of an overcorrected equinocavovarus deformity (clubfoot)

Contraindications

Lengthening the lateral column is not recommended in the setting of

AAFD with a normal calcaneal pitch angle and/or without increased hindfoot valgus

Rigid pes planovalgus (Stage III PTTD)

Tetralogic pes planovalgus in children or adolescents

Stiffness of the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints that precludes full, passive correction of all the concomitant deformities associated with the flatfoot

Active (Eichenholtz stage 1 or 2) Charcot osteoarthropathy

Reconstruction of late-stage (Eichenholtz stage 3) Charcot deformity with osteomyelitis or the presence of a deep space infection due to a neuropathic foot ulcer

Children under the age of 10 years

Lengthening the lateral column may not be recommended in the setting of

Monofilament-insensate foot secondary to diabetic peripheral neuropathy

Reconstruction of a late-stage (Eichenholtz stage 3) Charcot foot with severe bone loss or deformity in the midfoot

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation must precede the decision to indicate a painful AAFD for a lateral column lengthening.

The surgeon must assess the constituent deformities of the AAFD with the patient standing.

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs with the patient in full weight bearing must be obtained.

Also, the flexibility of these deformities must be assessed.

A supple flatfoot corrects by inverting the calcaneus through the subtalar joint and plantarflexing and adducting the navicular through the talonavicular joint.

Forefoot varus must be correctable. The metatarsals must derotate in the coronal plane when the calcaneus is held in a neutral position.

The constituent deformities to assess include

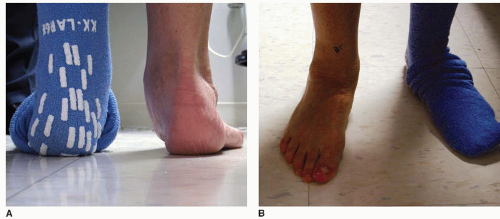

Hindfoot valgus, manifested as lateral deflection of the heel relative to the ankle, is best appreciated while viewing the patient from behind (Fig. 20.1A). The leg must also be visualized to determine if valgus tilting of the ankle contributes to the deformity.

Radiographically, hindfoot valgus can be measured from a hindfoot alignment view using a technique described by Saltzman (15).

Midfoot abduction also may be assessed from this vantage point. Qualitatively, the amount of midfoot abduction can be determined by the “too many toes” sign (Fig. 20.1A). Increasing abduction allows a greater number of lesser toes to be seen from behind. From this posterior view, the arch is absent and replaced with a prominence created by a plantarflexed and uncovered head of the talus in contact with the floor.

Midfoot abduction observed as lateral deviation of the foot may be seen while viewing the patient from the front (Fig. 20.1B).

Abduction is quantified radiographically by measuring the talonavicular uncoverage angle on a weight-bearing anteroposterior x-ray of the foot (Fig. 20.2A) (16, 17 and 18). Recently, stage II PTTD has been subdivided into three categories with stage IIB signifying that significant midfoot abduction comprises the flatfoot (19). A revised classification scheme offers that lateral column lengthening is warranted when the AAFD demonstrates uncoverage of talonavicular joint exceeding 40% of the articulation. Lateral incongruity of the talonavicular joint as measured by the angle created by lateral subluxation/rotation of the navicular relative to the lateral talar neck has been advanced as a reliable radiographic indicator of the presence of a stage IIB deformity and the need for a lateral column lengthening.

Forefoot varus represents the combined effect of supination of the foot and elevation of the medial column to maintain a compensated, plantigrade foot during weight bearing in the presence of hindfoot valgus.

The flexibility of forefoot varus in pes planovalgus can be evaluated dynamically by asking the patient to externally rotate the knee while standing. In flexible forefoot varus, as the heel inverts toward the midline, the arch returns and the first metatarsal head maintains contact with the floor. During this maneuver, the patient corrects their forefoot varus by derotating the foot and plantarflexing the first ray through active contraction of the posterior tibial and peroneus longus muscles. With fixed forefoot varus, the first metatarsal lifts off the floor, and the arch does not return because the joints along the medial column do not move with muscle contraction. The presence of fixed forefoot varus indicates that realignment and stabilization of the medial column must accompany a lengthening of the lateral column during reconstruction to achieve a plantigrade foot.

Radiographically, forefoot varus can be quantified by measuring the talo-first metatarsal angle on the lateral weight-bearing view (Fig. 20.2B).

The surgeon must identify musculotendinous and soft tissue pathology and that may coexist with AAFD.

Equinus contracture. The Silfverskiöld test will determine the origin of an equinus contracture (20). If ankle equinus resolves with knee flexion, the contracture is isolated to the gastrocnemius. If equinus does not change whether the knee is flexed or extended, then the Achilles tendon is contracted. Isolated contractures are corrected with a recession of the gastrocnemius, while a lengthening of the Achilles is necessary for a combined contracture of the triceps surae (Fig. 20.3).

Peroneus brevis contracture. In severe abduction or anatomical shortening of the lateral column, the peroneus brevis tendon becomes contracted. A lengthening or transfer of this tendon to the peroneus longus is required to allow full correction of an abducted midfoot.

Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree