Lacertus Syndrome in Throwing Athletes

Steve E. Jordan MD

History of the Technique

In 1959, George Bennett1 summarized his experiences caring for throwing athletes. The following paragraph is excerpted in its entirety from that article.

There is a lesion which produces a different syndrome. A pitcher in throwing a curve ball is compelled to supinate his wrist with a snap at the end of his delivery. This movement plus extension leads to the development of an irritation in front of and below the internal condyle of the humerus, which is extremely disabling. On examination, one will note distinct fullness over the pronator radii teres, beneath which are the tendinous attachments of the brachialis and the flexor sublimes digitorum. These are covered by a strong fascial band, a portion of which is the attachment of the biceps, which runs obliquely across the pronator muscle. A pitcher may be able to pitch for two or three innings but then the pain and swelling become so great that he has to retire. Roentgenograms in the majority of cases are entirely within normal limits, and my experience shows that exploration of the joint reveals no pathology and, therefore, is not advised. The muscle tissue generally is normal in appearance. A simple linear and transverse division of the fascia covering the muscles has relieved tension on many occasions and rehabilitated these men so that they were able to return to the game. I am at a loss to explain it except that tension develops from some unidentified irritation to the muscle tissue, or it is quite possible that this may be secondary to an irritation of the ulna at its articulation with the internal condyle.

This is the first known reference to a condition that has undoubtedly disabled many players and possibly ended careers of an untold number of throwing athletes. While Bennett did not fully understand the causes or even the mechanics involved (i.e., he thought the pitcher supinates instead of pronates upon release of the baseball), he did describe a simple operative treatment that has allowed us to prolong the careers of several throwing athletes. I have successfully treated 24 athletes diagnosed with a postexertional compartment syndrome of the medial elbow called the lacertus syndrome.

Indications and Contraindications

Athletes with the lacertus syndrome usually present with a vague history of slowly increasing discomfort in the flexor-pronator muscles after throwing. The discomfort is described as an achy painful tightness of the medial elbow, which develops in the first few hours after activity. Initially, the symptoms are minor and often ignored. A few hours rest leads to complete relief. As the condition progresses, the symptoms increase in severity and duration, and it requires a longer period of rest to relieve the discomfort and return to throwing. Just as Bennett described, these symptoms may progress to the point that the player cannot continue throwing. For position players in baseball, this problem is often not debilitating; however, for pitchers it may be. Quarterbacks complain most often during the repetition of practice. It is at this point, when the symptoms have progressed to a degree that they interfere with participation that the player usually presents to the trainer or doctor.

The duration of symptoms may vary markedly. In our series, symptoms ranged from eight hours to 4 days before resolving, only to begin again if the athlete threw too much. Duration of recurrent symptoms ranged from 6 months to 3 years. In all patients the symptoms were disabling if the throwing activity resumed before the acute symptoms had resolved.

The key feature of the history in patients with the lacertus syndrome is the delayed onset of symptoms, which is like

that seen in exertional compartment syndromes of the legs in runners. This, together with the fact that a period of rest allows the athlete to resume throwing without discomfort, is diagnostic. Trauma to the elbow is usually not a factor in the etiology of the lacertus syndrome. The physician should take a careful history and perform a thorough physical exam of the elbow to help rule out more common abnormalities such as medial epicondylitis, ulnar collateral ligament injuries, and cubital tunnel syndrome or ulnar neuritis. Other conditions that can cause medial elbow pain in throwers are bicipital tendonitis and stress fractures. Pronator teres syndrome or intra-articular pathologies should also be considered and ruled out.

that seen in exertional compartment syndromes of the legs in runners. This, together with the fact that a period of rest allows the athlete to resume throwing without discomfort, is diagnostic. Trauma to the elbow is usually not a factor in the etiology of the lacertus syndrome. The physician should take a careful history and perform a thorough physical exam of the elbow to help rule out more common abnormalities such as medial epicondylitis, ulnar collateral ligament injuries, and cubital tunnel syndrome or ulnar neuritis. Other conditions that can cause medial elbow pain in throwers are bicipital tendonitis and stress fractures. Pronator teres syndrome or intra-articular pathologies should also be considered and ruled out.

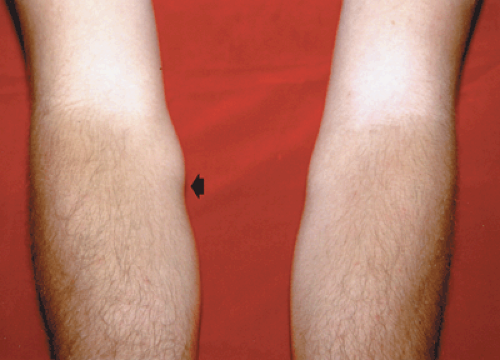

In patients who have a history of postexertional medial elbow pain and tightness and who have the lacertus syndrome as part of their differential diagnosis, it is essential to examine the player after a workout. The examination should begin with a careful inspection of the arm, looking for abnormal contours of the medial musculature just distal to the medial epicondyle. In players with severe or advanced cases, the proximal portions of the flexor pronator muscles appear grossly swollen and the distinct oblique band of the lacertus fibrosus is readily visible (Fig. 32-1). The patient should be asked to flex and pronate the wrist, which further exaggerates any abnormality in the area of the lacertus fascia. Palpation of the area will likely reveal tenderness in the muscle directly beneath and just distal to the crossing fascial band.

Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging exams are performed to help exclude other more common diagnoses. There are no findings on these studies to confirm the diagnosis of lacertus syndrome, but the tests are obviously helpful in ruling out other conditions. The diagnosis of lacertus syndrome can usually be made with a careful history and physical exam alone.

High-speed video of the pitching motion has revealed that pitches are released with a terminal pronation of the hand and forearm.2 Although Bennett was incorrect in his assertion that curveball pitchers supinate upon release, he was correct in his belief that curveball pitchers are more prone to develop the lacertus syndrome. Sixty-six percent of the pitchers in our series listed the breaking ball as their prominent pitch. The curveball is held during the acceleration phase of pitching with greater supination of the hand, putting more stretch on the pronator teres than seen in a fastball or change-up, both of which are normally held in a forearm neutral position during acceleration. This may lead to more work for the pronator muscles in the release of a breaking ball and thus account for the greater propensity of breaking ball pitchers to develop the condition. Repetitive pronation of the forearm is the mechanism that leads to the symptoms.

The pathophysiology of the lacertus syndrome is similar to that of exertional compartment syndrome in the legs of runners.3 The lacertus syndrome differs from compartment syndromes of the leg due to the peculiar anatomy of the lacertus fascia. The lacertus fibrosus fascia is not the primary muscle fascia for the flexor pronator group of muscles. It does not define an entire compartment; it merely invests a portion of the muscle compartment acting as an extrinsic constrictor and prevents normal tissue expansion during and after exercise. Postexercise compartmental pressure measurements taken in symptomatic patients revealed pressures 15 to 22 mm Hg greater under the area of the lacertus fascia than in the same muscles proximal to the crossing lacertus fascia. Therefore, the pathophysiology of the lacertus syndrome is that of a partial compartment syndrome. Only the tissue below the crossing fascia has elevated pressures, and it is here that the symptoms are generated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree