A Hyperextension deformities of the knee The boy’s knees hyperextend due to generalized joint laxity. The girl’s have a hyperextension deformity due to a knee injury with loss of knee flexion.

Hyperextension,

if associated with stiffness, is called a recurvatum deformity. Restricted motion is described by specifying the arc of motion. For example, a stiff knee may be described as having an “arc of motion from 20 to 55 degrees.” The arc of motion in hyperextension is preceded by a minus sign. A child with a hyperextension deformity may have a range from -20° to 30°, giving a 50-degree arc of motion.

The knee angle

is the thigh–leg angle or femoral–tibial angle (see Chapter 8). Changes in the knee angle that represent normal variations are physiological and cause bowlegs or knock-knees. Deformities, those falling outside the normal range (±2 SD) and those due to pathological processes, are termed genu varum or genu valgum.

Normal Development

The knee develops as a typical synovial joint during the first two fetal months. The secondary centers of ossification for the distal femur form between the sixth and ninth fetal months and for the upper tibia between the eighth fetal and first postnatal months. The patella ossification center appears between the second and fourth years in girls and the third and fifth years in boys.

Developmental Variations

Variations of ossification or development may cause confusion in assessing radiographs.

Bipartite patella

is due to an accessory ossification center of the patella that usually occurs in the superior–lateral corner [B].

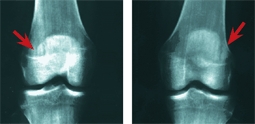

B Bilateral bipartite patellae Secondary centers may appear on both knees. They are usually asymptomatic.

Fibrocortical defects

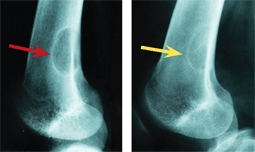

are usually insignificant developmental variations that are most common about the knee. They are eccentric and show sclerotic margins and radiolucent centers. They resolve spontaneously [C].

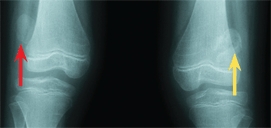

C Fibrocortical defect This is a typical large lesion in the distal femur (red arrow). Two years later, spontaneous healing has occurred (yellow arrow).

Evaluation

Evaluating the child’s knee is different from evaluating the knee of the adult because disorders are more likely to be due to some underlying generalized dysplasia or to focal congenital or developmental deformity.

Screening Examination

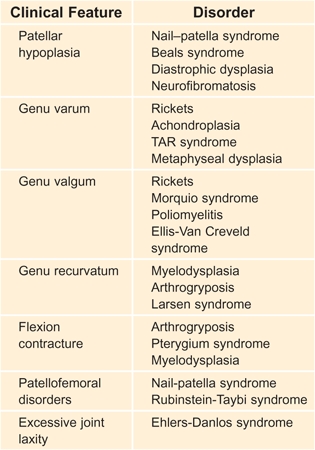

Screen for some underlying abnormality [A], such as nail–patella syndrome [B]. Asymptomatic dislocation of the patella is common in Down syndrome. Dimpling over the knee is common in arthrogryposis. Recurvatum occurs in spina bifida and in arthrogryposis. Genu varum and valgum are common in ricketic disorders, and genu valgum is common in Morquio and Ellis-Van Creveld syndromes.

A Syndromes associated with knee deformity These are examples that illustrate the relationship of knee deformities in various generalized disorders.

B Nail–patella syndrome Note the nail dysplasia and absence of the patella.

Physical Examination

The physical examination usually provides the diagnosis or at least the basis for ordering further studies.

General inspection

Look for obvious deformity, check the knee angle, and perform a rotational profile [C].

C Inspection The screening examination of this standing child shows the shortening and bowing of the left tibia (yellow arrow) and the café-au-lait spots of neurofibromatosis. Severe flexion contractures are present in the popliteal pterygium syndrome (red arrows).

Knee

Observe the child standing and note symmetry, knee angle, position of patella, masses, joint effusion, muscle definition and atrophy [D], and signs of inflammation. Is there full extension or hyper extension?

D Hypoplasia of the quadriceps Hypoplasia is a common dysplastic feature in patellofemoral disorders in children and adolescents (arrows).

Patellar tracking

Ask the child to sit and slowly flex and extend the knee. Observe the tracking of the patella. Does it move in a linear fashion or displace laterally as the knee extends [E]? Repeat the examination with the hand on the patella as the knee is flexed both actively and passively. Does the patella move smoothly and track in the midline? Does the knee fully flex and extend?

E Patellar tracking As the child slowly extends the knee, the patella normally tracks vertically. Lateral patellar displacement as the knee becomes fully extended (arrow) is described as “J” tracking.

Q angle

is the angle formed by a line connecting the anterior superior iliac spine with the midportion of the patella and a second line from the patellar midpoint to the tibial tubercle. Normally, the enclosed angle is less than about 15°. Be aware that the Q angle has no direct relationship with knee pain or patellar instability.

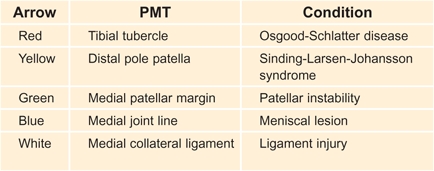

Point of maximum tenderness

Locate the PMT by systematically examining the entire knee and tibia. The PMT often establishes a working diagnosis [A, facing page].

A Point of maximum tenderness Evaluate the PMT for common painful conditions about the knee.

Palpate

to assess temperature, swelling, and tenderness. Is the affected knee warmer than the other knee? Is a joint effusion present [B]? Parapatellar fullness suggests a joint effusion. Evaluate any fullness by extending the knee, compressing the suprapatellar region, and checking for a fluid wave in the knee. A posttraumatic effusion is a sign of a significant intraarticular injury such as a torn peripheral meniscus, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, or osteochondral fracture. Do not confuse prepatellar swelling with an intraarticular effusion.

B Knee tests Compressing the suprapatellar bursa (red arrows) displaces any joint fluid into the joint to demonstrate an effusion. Displacing the patella laterally (yellow arrow) may elicit the patellar apprehension sign.

Manipulate

to determine if the patella is displaceable. In loose-jointed children, the patella is very mobile and more likely to dislocate.

Patellar apprehension

is elicited by extending the knee and attempting to displace the patella laterally [B]. Patients with recurrent dislocations who sense that this may cause the patella to dislocate may become apprehensive and may reach out to stop the examination.

Knee motion

Is the arch of motion free and unguarded? Is crepitation or snapping present?

Lachman test

Test anteroposterior laxity with this test. Flex the knee about 15°–20° and attempt to displace the tibia anterior in its relationship to the femur. Normally, a firm endpoint will be felt. Check for instability with varus and valgus stress [C]. With the knee flexed to a right angle, evaluate for anterior or posterior drawer signs.

C Knee stability Test for medial lateral instability with the knee flexed to 30°. Test the opposite or normal knee to determine what is normal for the child.

Rotational instability test

Test the pivot-shift for ACL injury and capsular laxity by extending the knee fully and apply valgus and internal rotation stress to demonstrate anterolateral tibial subluxation.

Perform the reverse pivot shift test by first flexing and externally rotating the knee. Next, extend the knee to demonstrate postero-lateral capsular laxity associated with PCL injury.

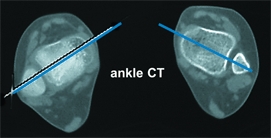

Imaging Studies

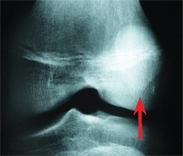

Special radiographic projects such as sunrise and notch views [D] may be useful. If conventional radiographs are not adequate, order special imaging studies [E].

D Notch view The condylar fracture is seen only in the notch view (red arrow).

E Special imaging studies These special studies demonstrate lateral patellar positioning (red arrows), and a hemangioma by MRI (yellow arrow).

Bone scans

may be helpful in determining the location or activity of lesions. The study is sensitive but not specific.

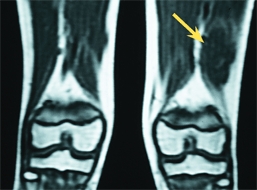

MRI studies

are overused and not appropriate for screening and are frequently overread, even in normal knees. They may be useful for ligamentous and meniscal injuries when correlated with clinical findings.

Ultrasound

is useful for cysts and pre-patellar swelling evaluation.

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy is essential for assessing meniscal injuries and for other ligamentous and osteochondral problems in children. It is less valuable for assessing pain.

Knee Pain

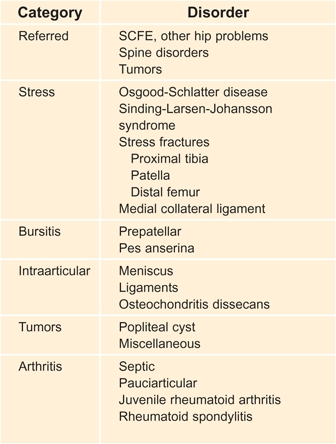

Knee pain is a common presenting complaint [A].

A Classification of knee pain Knee pain has many causes. Some examples are listed.

Referred Pain

First consider the possibility of referred pain from slipped capital femoral epiphysis [B], the spine, or from a tumor.

B Pitfalls in evaluating knee pain Referred pain can occur from this slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Note the subtle changes in the proximal metaphysis (arrow) consistent with a preslip.

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson Disorder

Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome is a traction apophysitis of the distal pole of the patella [C]. The condition is most common in males at or before puberty. Resolution occurs in 6–12 months. Rest the knee to resolve the pain and tenderness. Quadriceps flexibility exercises are commonly prescribed. No residual disability has been reported.

C Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome Note the separate lesion of the distal pole of the patella. This should be differentiated from the uncommon type of bipartite patella involving the inferior pole of the patella.

Pes Anserina Bursitis

Inflammation of the pes anserina bursa causes pain and tenderness over the hamstring tendon insertions on the posterior medial aspect of the upper tibial metaphysis. Evaluate for lower extremity malalignment. This uncommon condition occurs during the teen years. Manage the bursitis with rest and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications.

Medial Collateral Ligament Pain

Medial collateral ligament pain is an overuse condition causing pain and tenderness over the medial collateral ligament. This ligament lies on the posteromedial aspect of the knee at or above the joint line.

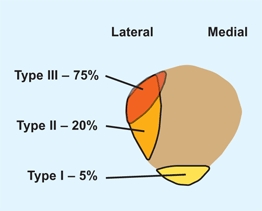

Bipartite Patella

Accessory centers of ossification of the patella [D] may produce a bipartite patella. These variations are classified into three types [E]. The separate ossicle is attached to the body of the patella by fibrous or cartilaginous tissue. Trauma may disrupt this attachment, and the ossicle then becomes painful. The disruption may heal with rest. In others, healing fails to occur and the ossicle remains chronically painful. Small painful ossicles may be removed. Larger ossicles should be fixed with a screw to the patella and grafted to promote union.

D Bipartite patella Note the separate ossicle on the superolateral aspect of the patella, consistent with a type III lesion. This lesion was painful.

E Classification of bipartite patellae These variations occur on the lateral and inferior aspects of the patella. Note the common type III involves the superior-lateral aspect of the patella. From Saupe (1921).

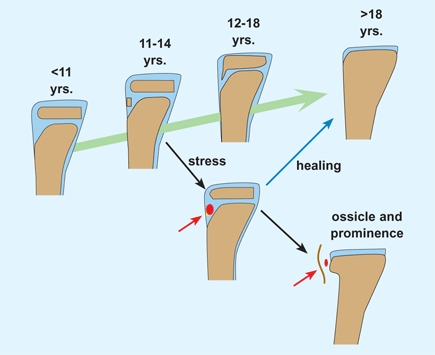

Osgood-Schlatter Disease

Osgood-Schlatter disease (OSD) is a traction apophysitis of the tibial tubercle due to repetitive tensile microtrauma. It occurs between ages 10 and 15 years, with the onset in girls about 2 years before that in boys. OSD is usually unilateral and occurs in 10–20% of children participating in sports. OSD is associated with patella alta.

Cause

The condition is due to a differential growth rate between bone and soft tissues. Whether this association is a cause or the result of OSD is not known. The tibial tubercle may be enlarged on the asymptomatic side. OSD may be associated with patella alta.

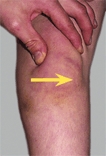

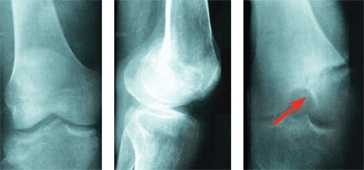

Clinical Findings

Clinical findings will demonstrate swelling and localized tenderness over the tibial tubercle [A] and no other abnormalities. Order a radiograph if the condition is unilateral or atypical. Radiographs usually show soft tissue swelling and fragmentation of the anterior apophysis.

A Osgood-Schlatter disease Note the prominence and the ossification over the tibial tubercle (red arrows). Persisting tenderness over an ossicle in the mature knee (yellow arrows) is an indication for excision.

Natural History

OSD resolves with time in most children [B]. In about 10% of knees, some residual prominence of the tibial tubercle or persisting pain from an ossicle may cause problems.

B Natural history of OSD The normal development of the apophysis is shown by the green arrow. Excessive traction (red) of the patellar tendon causes inflammation. Usually this process heals (blue arrow). In some cases, inflammation and a separate ossicle persist (red arrows). Based on Flowers and Bhadreshwar (1995).

Manage

Manage based on severity of discomfort. Modify activities, use NSAIDs, and use a knee pad to control discomfort. If OSD is severe or persists, apply a knee immobilizer for 7–10 days to relieve inflammation. Injection of steroids is not recommended. Quadriceps and hamstring flexibility exercises are the most useful treatment.

Managing the family

To reduce apprehension, consider referring to ODS as a disorder or condition rather than a disease when discussing the problems with the patient and family. Make certain that they are aware that resolution is usually slow, often requiring 12–18 months.

Persisting disability

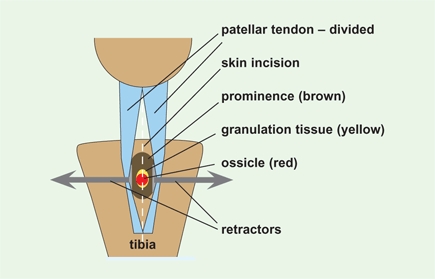

from tenderness and tubercle prominence may be sufficient to require excision of the ossicle and prominence [C].

C Excision of the ossicle and prominence The procedure is performed through a midline incision to the ossicle and prominence. Sometimes inflammatory granulation tissue is present in active lesions.

Complications

are rare and include growth arrest with recurvatum deformity and rupture of patellar tendon or avulsion of the tibial tubercle.

Osteochondritis Dissecans

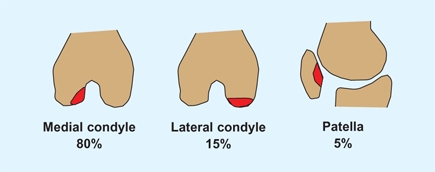

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is an idiopathic lesion of subchondral bone that may resolve spontaneously. Progressive lesions may involve the overlying articular cartilage. These lesions are most common about the knee, usually involving the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle [A]. Patellar lesions usually occur later than those of the condyles.

A Sites of knee involvement Most lesions occur on the posterolateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle.

Cause

The cause is multifactorial with trauma, vascular insufficiency, and genetics being factors. OCD lesions are associated with lateral tibial torsion, genu varum and valgum, and meniscal lesions.

Clinical Findings

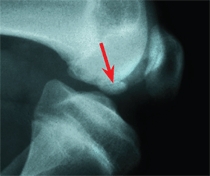

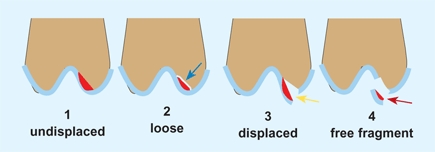

Juvenile OCD occurs in children 5–15 years of age, with an average age of onset between 11 and 14 years. Boys are more commonly affected. Symptoms include pain, a mild effusion, or later mechanical symptoms. Because most lesions involve the posterolateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle, they are best shown by a notch view [B]. Classify lesions based on degree of displacement [C]. Sometimes the displacement can be appreciated only on MRI or arthroscopy [D].

B Radiographic appearance The standard AP radiograph shows the common lesions rather poorly (yellow arrow). Lateral radiographs may show lesions without displacement (orange arrow) or better defined fragments with impending displacement (red arrow).

C Classification of osteochondritis dissecans The lesion (red) may be undisplaced or be loosely in place (blue arrow). Displacement may be partial (yellow arrow) or complete (red arrow), allowing the fragment to be free in the joint.

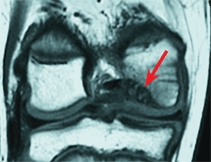

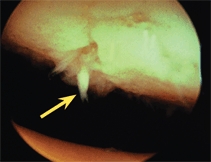

D Imaging MRI demonstrates a large defect (red arrow) with intact cartilage. Arthroscopy shows a lesion with overlying irregular cartilage (yellow arrow).

Irregular ossification of the lateral femoral condyle may be a normal variation of ossification and not osteochondritis dissecans. These variations are often bilateral and found incidentally when radiographs of the knee are made. They do not cause pain or effusion, and are nontender.

Natural History

Small lesions in children or early adolescence often resolve without treatment. Larger lesions, older age, and a weight-bearing location are more likely to displace and cause joint damage and eventual osteoarthritis. Aggressive treatment of these lesions is appropriate.

Management

Management depends upon the site, size, patient’s age, and classification of the lesion.

Type 1 and 2 lesions

Manage with activity modification, isometric exercises, and a knee immobilizer. Manage based on symptoms rather than on radiographic appearance. Radiographic healing takes many months.

Type 3 lesions

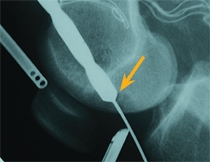

Manage by drilling and stabilizing with K wires [E] or absorbable pins.

E Operative treatment The lesion may be drilled and fixed with K wires (yellow arrow). A large drill may be required for larger lesions (orange arrow).

Type 4 lesions

Manage small lesions by excision. Replace large lesions or those involving the weight-bearing areas and fix internally if adequate subchondral bone exists on the fragment.

Prognosis

Up to 90% of small lesions in juvenile OCD may heal spontaneously. Lesions with an onset later, especially large lesions in weight-bearing regions of the knee, require aggressive treatment. Management is not always successful, and osteoarthritis may occur in adult life.

Anterior Knee Pain

Anterior knee pain is common during the second decade and may occur in up to a third of adolescents. This pain may be associated with some underlying patellofemoral malalignment or may be idiopathic, occurring in normal individuals.

Structural Anterior Knee Pain

Pain associated with some knee dysplasia is more serious and often requires operative correction.

Evaluation

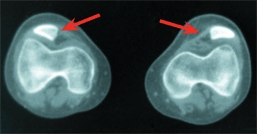

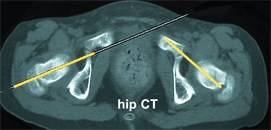

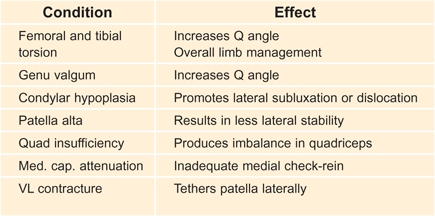

Identify the underlying dysplastic features, such as lateral tibial torsion, genu valgum, patella alta, quadriceps hypoplasia, lateral tether, shallow sulcus, or excessive joint laxity. Consider imaging the patellofemoral joint with a CT scan to rule out patellar malpositioning [A].

A Severe rotational malalignment syndrome This child had habitual dislocations at age 5 years. Realignment was performed on the worse left side. She was not seen again until age 10 years. At that time, shown here, she was asymptomatic. Her left patella was subluxated and right patella dislocated. The child has severe rotational malalignment, as demonstrated by CT scans. Note that the bicondylar axis is medially rotated 30° (yellow lines). This results in 60° of anteversion (red lines) and about 75° of lateral tibial torsion (blue lines). Note the displaced patella (red arrows) and the shallow condylar grooves (yellow arrows). It was elected not to attempt operative repair because rotational osteotomies of both femora and tibiae and realignment would be necessary. The chance of success was considered too poor to justify the magnitude of the procedures. This case demonstrates the complex pathology of some types of congenital development patellofemoral disorders.

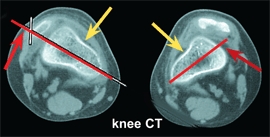

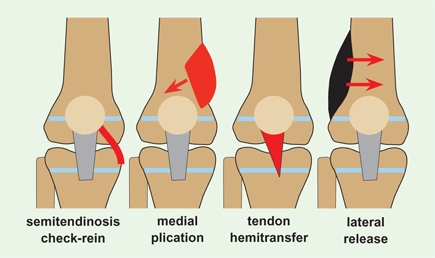

Management

Manage first with NSAIDS and isometric exercises. During the first visit, introduce the possible need for a realignment procedure [B]. Identify and, if possible, quantitate the severity of each dysplastic feature. Correct obvious manageable deformities early. In other cases, the decision is difficult. For example, bilateral double-level osteotomies are necessary to correct severe rotational malalignment. Thoughtfully place the operative incision [C].

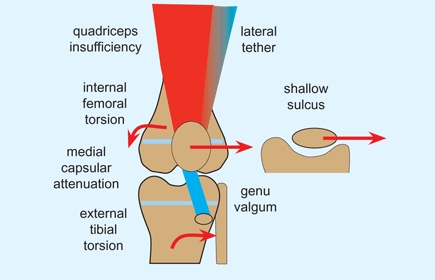

B Components of operative repair These components are usually combined to correct all dysplastic features. The lateral release alone is usually inadequate.

C Operative knee scars Knee scars cause considerable disability (red arrow). A midline vertical incision is optimal for extensive realignment procedures (yellow arrows).

Idiopathic Anterior Knee Pain

This pain is common among teenagers, especially girls, and is often associated with a period of rapid growth. The pain is often activity related, is poorly localized, and may cause disability. It has been described as the headache of the knee. About one-third of these patients have features of the MMPI found in individuals with nonorganic back pain. Its natural history is one of spontaneous improvement over a period of years.

Diagnosis

This pain involves a history of discomfort after sitting; pain with exercise, walking down stairs, or with sitting and squatting; a crunching sound with walking up stairs; and/or a sense of giving way with jumping or running. Often it is most prominent in the morning or after sitting and improves with time and warm up. When asked to localize the pain, the patient will often grab the entire front of the knee (grab sign).

Cause

The causes are numerous and often associated with muscle imbalance. Aggravating factors may be poor training and shoeware.

Management

Prescribe NSAIDS, isometric exercises, activity modification, and reassurance. Sometimes applying ice reduces discomfort. Sometimes a knee sleeve with a patellar cutout seems to help. Avoid arthroscopy and lateral release procedures.

Rehabilitation

After the acute phase has passed, the patient should establish flexibility and strength before gradually resuming full activity. Stretching should be painfree.

Prevention

Suggest warm up and stretching before activity, and avoiding activities that cause pain. This may require modification of activities by substituting others that are less stressful for the knee.

Patellofemoral Disorders

Many factors may contribute to patellofemoral instability [A].

A Factors contributing to patellofemoral instability These factors combine to increase the risk of patellar subluxation or dislocation.

Systemic Disorders

Patellofemoral instability is more common in children with (1) knee dysplasias, such as occurs in nail–patella syndrome [B], Rubinstein–Taybi syndrome, and Turner syndrome and (2) conditions with increased joint laxity such as Down syndrome. These underlying conditions complicate management.

B Patellar hypoplasia This deformity was part of the nail–patella syndrome.

Congenital Dislocation

Congenital patellar dislocation is a rare condition that causes a progressive flexion, valgus, and tibial external rotational deformities of the knee. Reduce the dislocation and realign the quadriceps mechanism late in the first year. An extensive lateral release is often required.

Patellar Subluxation or Dislocation in Childhood

So-called habitual subluxation or dislocation is usually due to a dysplastic knee with contracture of the lateral portion of the quadriceps mechanism. This causes the patella to displace laterally whenever the knee is flexed. Early operative realignment is appropriate, but because the dysplastic features are severe, recurrence is common.

Traumatic Patellar Subluxation or Dislocation

Traumatic patellar dislocations cause an articular fracture. If the injury is severe, producing a tense hemarthrosis, arthroscopic evaluation may be appropriate.

Adolescent Recurrent Dislocation

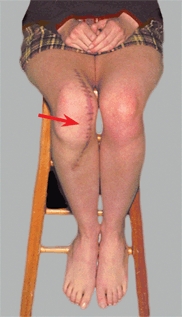

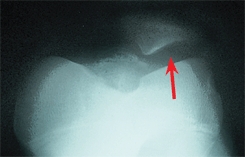

Most recurrent dislocations occur in individuals with dysplastic knees. They may show generalized joint laxity, lateral tibial torsion, genu valgum, hypoplasia of the quadriceps [C], attenuation of the medial joint capsule, limited medial mobility of the patella, and abnormal patellar tracking. Observe the tracking of the patella as the patient slowly extends the knee. Lateral displacement of the patella as the knee nears full extension is described as J tracking. J tracking is a common finding. Sometimes the patella becomes subluxated with a sudden lateral shift. The patellar apprehension sign may also be positive. The patient becomes fearful that the patella will dislocate when the examiner applies lateral pressure to it. Radiographs may show lateral displacement of the patella [D].

C Quadriceps hypoplasia Note the loss of delineation of the VMO. The hypoplasia and weakness contribute to patellar instability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree