1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The emergence of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in France and worldwide (with the associated pandemic risk) has prompted the French health authorities to publish guidelines on control and limiting the spread of these bacteria .

The high prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBLPE) and the exposure of hospital populations to carbapenemes appear to favour the emergence of resistant bacteria . Klebsiella pneumonia carbapenemase (KPC)-producing isolates are the most widespread highly resistant bacteria (HRB).

Infections caused by multiresistant, KPC-producer are associated with a high mortality rate (22–57%), which makes the outcome of probabilistic approaches to antibiotic therapy uncertain and complicates the course of treatment .

Physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM) departments must take account of the spread of KPC-producer because lengths of stay are longer than in acute care departments, and care procedures and the frequent movements of patients within the unit are interrelated.

The objective of the present report was to describe our department’s management of an epidemic of KPC-producer and our implementation of the drastic changes in organisational structure that were required to halt the spread of the bacteria over an 8-month period.

1.2

Observation

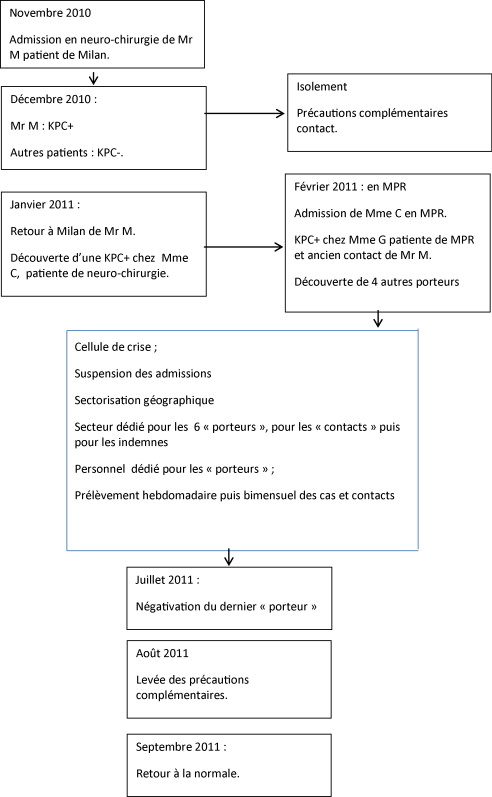

At the end of November 2010, a patient was admitted from his home (in Milan, Italy) for scheduled surgery in our institution’s neurosurgery department. A month later, a fortuitous screening procedure revealed that the patient was carrying KPC-producer. As a result, he was confined to his room and additional contact-limiting precautions were implemented. In three successive screens, all the patients in the neurosurgery department were found to be negative for KPC-producer. On January 25th, 2011, the patient returned to Italy. On the same day, the KPC-producer was discovered in another patient in the neurosurgery department. She was nevertheless admitted to our PRM department for specific care on February 1st, 2011, and adequate precautions had been taken. Another patient in our department (who had been in contact with the patient from Italy) then screened positive for the strain. Hence, at this point in time, two of our patients were carrying KPC-producer ( Fig. 1 ).

From that time on, a certain number of measures were implemented. A crisis management team was set up: it comprised representatives of the local and regional nosocomial infection management committees, our hospital’s senior management, the operational hygiene team, the medical staff and the care and rehabilitation staff. Admissions were suspended for two weeks.

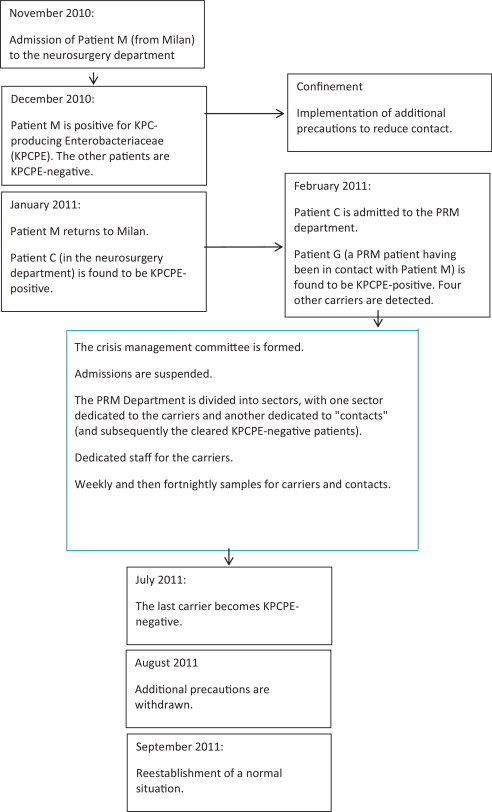

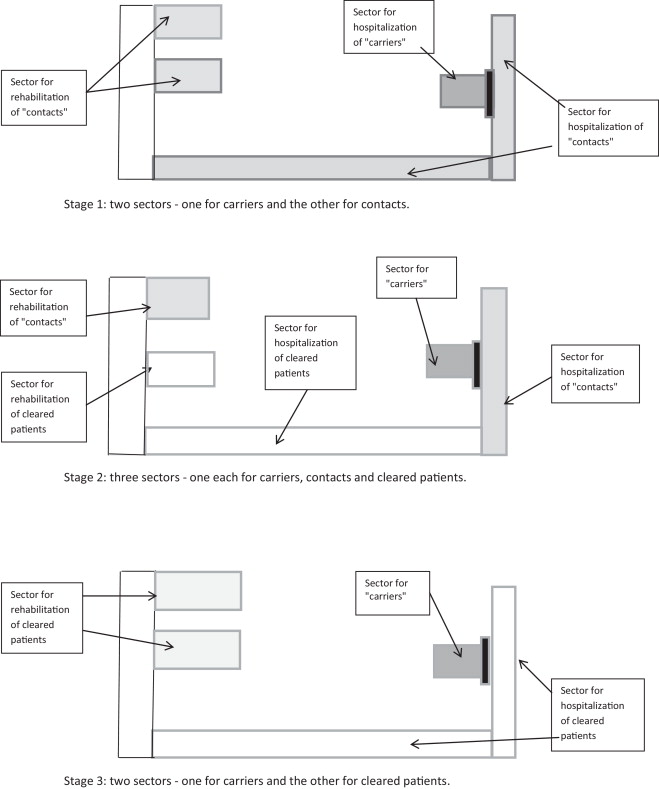

Our bed layout was reorganized; the KPC-producer-positive patients (referred to henceforth as “carriers”) were placed in a dedicated sector with dedicated personnel and a controlled entry/exit zone. The second “contact” sector housed patients who had been in contact with the two “carriers”. Once enough, patients had been discharged, a third sector was created for KPC-producer-negative patients (non-carriers).

Rehabilitation care was also reorganised, with “carriers” receiving care in their rooms. The “contact” patients and “non-carriers” underwent rehabilitation in two different areas. Once the number of “contact” patients had fallen, rehabilitation care was delivered in the same areas but at different times of the day (the morning for “non-carriers” and the afternoon for “contact” patients) ( Fig. 2 ).

Rectal samples were collected from all “carriers” and “contact” patients weekly until August 1st, 2011, and fortnightly thereafter. All care procedures for “contact” patients complied with current guidelines on multiresistant bacteria (MRB).

In February 2011, there were six “carriers” (the two initial “carriers”, three positive screens from among the “contact” patients and another known “carrier” admitted from the neurosurgery department) and 38 “contact” patients. Of these six “carriers”, three were discharged to home, two were transferred to another PRM unit nearer to their home and one was transferred to a palliative care unit.

The last “carrier” became KPC-producer-negative in July 2011. On August 1st, 2011 (and after 20 to 25 negative rectal swabs for each patient), we were able to abandon our additional precautions for “contact” patients. On September 5th, 2011, we were able to abandon our “dedicated personnel” measures for the last “carrier” (after 11 negative rectal swabs) but maintained our MRB control procedures. Care procedures were normalized in October 2011, following the discharge of the last “carrier”.

This outcome came at the cost: 11 crisis management meetings; 543 rectal samples, 382 additional staff days (151 for nurses and 231 for nursing assistants) and greater expenditure on disposable material (2600 single-use pyjamas, for example).

Our department was unavailable for a total of 388 days, with the loss of about 15 admissions. The average length of hospitalization also increased, in view of the difficulty in discharging and transferring patients – even the “carriers” who were no longer positive and “contact” patients with three negative swabs. The workload had also increased and the psychological impact on patients, families and carers was significant. The confinement of “carriers” probably reduced the standard of care that we were able to provide.

A list of “carriers” and “contact” patients has been circulated within our hospital group and (with a view to future admissions of these patients) an alert system has been implemented.

1.3

Discussion

Although levels of awareness of the risk of PC-producing Enterobacteriaceae epidemics (or even pandemics) have increased, the management of MRB and HRB differ from one department to another and from one hospital to another. The management of MRB colonization in PRM departments has been described for various types of bacteria, units and preventive measures .

Two studies of patients with spine injuries observed a link between the presence of MRB and the administration of antibiotics in the preceding weeks or months. Furthermore, Ohana et al. reported a link with long hospital stays and the use of rooms with several beds. Both reports emphasized how difficult it is to confine patients as recommended by the guidelines, since this goes against the objectives of personnel independence and social integration in PRM. We decided to divide the service into several sectors, which had a non-negligible impact on the care delivery, workload, psychological burden and cost.

Our patients did not always understand why they had been confined to their rooms and sometimes said that they felt as if they had been abandoned. In 2001, Newton et al. found only weak evidence of the psychological impact of confinement , whereas other authors observed a strong impact . Webber et al. reported a loss of self-esteem and feeling of stigmatisation in confined patients .

Longer hospital stays by “carriers” and “contact” patients resulted from transfer difficulties. The latter were also highlighted by Mylotte et al. . Lastly, it is now accepted that a patient admitted from abroad must be confined if he/she has not been screened for MRB and HRB. However, it is known that these bacteria circulate within France – underlining the importance of high levels of awareness and application of the French High Commission for Public Health’s guidelines on this subject.

Although the measures implemented during the outbreak of KPC-producer infections in our service were severe and burdensome, they enabled us to halt the epidemic.

1.4

Conclusion

The emergence of MRB and HRB epidemics poses a certain number of problems – particularly in PRM units in which strict confinement reduces access to rehabilitation equipment and thus reduces the likelihood of a satisfactory rehabilitational outcome. The main difficulty is reconciling two contradictory objectives: the confinement measures required to stem the epidemic and patients’ mobility goals as part of their rehabilitation. It is essential to standardize practices and provide carers and patients with extensive, accurate information, with a view to limiting the psychological impact while enlisting their support in the fight against epidemic infections.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’émergence et la diffusion d’entérobactéries productrices de carbapénémase (EPC) en France et dans le monde avec menace d’une pandémie a amené les autorités sanitaires françaises à publier des recommandations ayant comme objectif de contrôler et limiter leur diffusion .

La prévalence aujourd’hui élevée des entérobactéries productrices de bêta-lactamase à spectre élargi (EBLSE) et l’exposition des populations hospitalières aux carbapénèmes semblent être des facteurs favorisant l’émergence de bactéries résistantes à ceux-ci . Parmi celles-ci, Klebsielle pneumoniae carbapénémase (KPC) est la plus répandue.

La mortalité liée à ces infections à KPC est élevée (22–57 %), du fait de la multi-résistance des souches, rendant l’antibiothérapie probabiliste incertaine et l’antibiothérapie thérapeutique difficile .

Le risque de la diffusion de telles bactéries est important à considérer dans les structures de médecine physique et de réadaptation (MPR) parce que les séjours sont plus longs qu’en service aigu et les soins et les mouvements des patients sont multiples et intriqués.

L’objectif de ce travail est de rapporter l’expérience de notre service qui a été confronté à la présence d’une KPC et l’organisation drastique nécessitée durant 8 mois pour en juguler l’extension.

2.2

Observation

Fin novembre 2010, un patient venant de son domicile à Milan était hospitalisé dans le service de neurochirurgie du groupe hospitalier pour une intervention programmée. Un mois plus tard, il était dépisté fortuitement porteur de KPC et bénéficiait alors d’un isolement avec mise en place des précautions complémentaires contact. Trois dépistages successifs de tous les patients de ce même service étaient négatifs. Le 25 janvier 2011, le patient rentrait en Italie et, le même jour, la KPC était découverte chez une patiente du même service. Celle-ci a été néanmoins acceptée dans notre service de MPR du fait de besoins spécifiques le 1 er février 2011 sous-couvert des précautions en vigueur. Une autre patiente de notre service, qui avait été en « contact » avec le patient de Milan a été alors dépistée positive. À cette date-là, il y avait donc 2 patientes porteuses de KPC ( Fig. 1 ).