Rajashree Srinivasan

Callenda Hacker

Nora Cubillos

![]()

31: Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

![]()

PATIENT CARE

GOALS

Provide patient care that is compassionate, appropriate, and effective for the treatment of a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) and the promotion of good health.

OBJECTIVES

1. Describe the key components of the assessment of the child with JIA.

2. Discuss the long-term outcomes of JIA.

3. Assess the impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions associated with JIA.

4. Describe the psychosocial, vocational, and educational aspects of JIA.

5. Describe potential injuries associated with JIA.

6. Formulate the key components of a rehabilitation treatment plan for the child with JIA.

ASSESSMENT OF THE CHILD WITH JIA

In performing a thorough history and physical examination, a clinician must be aware that there is no single pathognomonic finding for JIA. It is therefore important to look for patterns of signs and symptoms that may lead to the appropriate diagnosis.

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS

The child suspected to have JIA may complain of pain with ambulation, morning stiffness, “gelling” sensation, joint swelling, decreased activity level, decreased use of an arm or leg, fevers, rash, and difficulty with buttons and writing (1). JIA is associated with uveitis, which can be asymptomatic and lead to blindness. Uveitis is usually asymptomatic, but can present with photophobia, pain, redness, headache, and visual change. Isolated musculoskeletal pain is generally not JIA (1).

Past Medical History

It is important to ask about conditions related to the child’s specific type of JIA. These include psoriasis, uveitis, enthesitis, history of macrophage activating syndrome, pericarditis or myocarditis, splenomegaly, and history of lymphadenopathy. The clinician should also inquire about conditions associated with JIA in general, such as presence of osteopenia, micrognathia, leg-length discrepancy, growth impairment, and hearing loss, as well as specific treatments such as autologous stem cell transplantation for cases refractory to medications. Given the use of several medications for the treatment of JIA (see Current and Past Medications section), it is also important for physiatrists to inquire about conditions related to their use such as (a) nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (gastritis, hypertension, impaired renal function), (b) disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, ulcerative stomatitis, nausea, diarrhea, hair thinning, pulmonary fibrosis, exfoliative dermatitis), and (c) biologics (serious infection, malignancy, myelosuppression, optic neuritis, photosensitivity, rash).

Past Surgical History

Although surgeries for JIA are less common with advanced medical treatments, the physiatrist should nevertheless inquire about them in the treatment of JIA. These include (a) soft-tissue releases, (b) contracture releases, (c) total joint replacement, (d) osteotomy for severe bony deformities, (e) epiphysiodesis for leg-length discrepancy, and (f) synovectomy or tenosynovectomy for uncontrolled inflammation.

Current and Past Medications

The clinician should inquire about current and past use of medications commonly used to treat JIA. These include (a) NSAIDs or glucocorticoids; (b) DMARDs such as sulfasalazine, methotrexate (taken with folic acid to reduce side effects), and leflunomide; (c) biologic agents such as etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab; (d) selective costimulation pathway modulators such as abatacept, interleukin-1 (IL-1) antagonist anakinra, IL-lbeta antagonist canakinumab, and IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab; and (e) history of intraarticular steroid injections.

Current and Past Functional History

Physiatrists should obtain a thorough current and past functional history. Some pertinent questions include the following: (a) How long does it take the child to get out of bed? (b) Is the pain worse after sitting or lying a while? (c) Compared to prior visits, what is the child’s activity level? (d) Is the child still able to keep up with peers, or has he or she become more of a reader or video game player? (e) Is the child doing well (academically and socially) at school and can the child carry needed supplies from class to class? (f) Has the child been attending physical and occupational therapies? (g) Is the child performing the exercises in his or her home exercise program?

Social history/level of family support: The following are important questions to ask: (a) Who lives with the child? (b) Does the family encourage activity within limits of pain and does the family include the child in activities? (c) Is the child part of a social group at school and outside of school? (d) Is the child given his or her medications as written and is he or she willing to take them? (e) Are there any environmental factors contributing to noncompliance? (f) Are the child’s treatments covered by insurance?

Review of Systems Related to JIA

Pain and other specific complaints can occur with each subtype of JIA in different patterns and should be reviewed at each visit. Important questions to ask include the following: (a) Is sleep interrupted by pain? (b) Does the child have pain on awakening or later in the day after activities? (c) Which joints are affected by pain? (d) Have any joints been swollen? (e) How much and what type of pain medicine does the child take? (f) Is the child growing and gaining weight appropriately?

Oligoarticular JIA generally causes pain in the large joints. Polyarticular JIA tends to cause pain in the small joints of the hands and feet. The cervical spine and temporomandibular joint can also be involved. Children with systemic JIA may complain of fevers twice daily and evanescent rash possibly with Keener phenomenon (skin lesions along line of trauma). Uveitis is also associated with JIA and the child may have symptoms of a red, painful, photophobic eye that can be insidious in presentation.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

JIA presentation may be subtle. The most common presentation is a single swollen knee. Other small and/or large joints may have synovitis that is not always symmetric. Polyarticular JIA usually involves knees, wrists, and ankles. Children may have subcutaneous nodules. Boutonniere and swan neck deformities can also be seen. Range of motion (ROM) and flexibility may be decreased. Axial joints can also be affected. Later in the disease, asymmetric growth can be seen and patients may develop torticollis due to cervical spine involvement, decreased oral opening, and micrognathia due to temporomandibular joint involvement, conductive hearing loss due to middle ear involvement, hoarseness due to cricoarytenoid cartilage involvement, rheumatoid nodules, nail pitting, rash, and gait disturbance. Enthesitis-related JIA may have point tenderness over tendon insertion sites (tibial tuberosity and posterior heel) and mildly decreased ROM (ROM 0). Systemic JIA may also have pericarditis or myocarditis, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy (2). Children with enthesitis-related JIA might complain of pain, stiffness, and decreased mobility in the lower back, as well as red, painful, photophobic eyes (uveitis). Children with psoriatictype JIA demonstrate involvement of the hands and feet such as protruding sausage digits and nail bed changes.

Laboratory studies: There may be evidence of leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, elevated liver enzymes, and increased acutephase reactants. The clinician should not miss the potentially life-threatening macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) that is associated with systemic JIA. A common sign of MAS is a low erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (in contrast with a high sedimentation rate in systemic JIA exacerbation).

LONG-TERM OUTCOMES OF JIA

Systemic, rheumatoid factor (RF)-negative and -positive polyarthritis have the highest incidence of advanced joint damage and prospects for long-term disability. Radiologic joint damage occurs over time even in the absence of clinical symptoms. A prolonged active disease course leads to increased joint damage (3). Extraarticular damage (eye damage, growth retardation, pubertal delay), subcutaneous atrophy due to intraarticular glucocorticoids, leg-length discrepancies, avascular necrosis, striae rubrae, and abnormal vertebral curve occur often in systemic and enthesitis-related JIA. Pain is common early in the disease course but diminishes as patients complete puberty. Pain frequently keeps patients awake at night and causes daytime fatigue, which affects school, work, and hobbies (4).

IMPAIRMENTS, ACTIVITY LIMITATIONS, AND PARTICIPATION RESTRICTIONS ASSOCIATED WITH JIA

Activity limitations and participation restrictions are frequent in all subtypes of JIA but can improve over time, despite worsening radiologic joint damage (3). Approximately 20% of patients will continue to have activity limitations, especially in dressing and activities that require reaching. Of all subtypes of JIA, systemic JIA and children with wrist and hip involvement have the most activity limitations and participation restrictions over time that are most likely to persist into adulthood (3). The Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) for disability highly correlates with parent’s/patient’s assessment of pain, well-being, level of disease, and functional status. It is inversely correlated with remission (3,5). Historically, decreased activity was recommended, but studies have shown that muscle atrophy occurs rapidly secondary to local arthritis. Weight-bearing exercise increases bone mass, and increased bone mass improves muscle strength. Evidence shows that structured low-intensity programs can lead to improved physical fitness, quality of life, and functional abilities in kids with JIA (6). Moderate adherence to an exercise program has shown improved parental CHAQ scores. Exercise therapy has also been shown to assist preschool children in reaching and maintaining milestones. Weight-bearing exercise is not ideal for patients with large joint disease, and alternative exercise therapies that can be tried include yoga and tai chi. The goal is not only to increase activity in the present but to also make healthy habits for a lifetime (6).

PSYCHOSOCIAL, VOCATIONAL, AND EDUCATIONAL ASPECTS OF JIA

Most kids with JIA can expect to lead normal lives (7). However, at some point in the course of disease, JIA does affect relationships between family members as well as intimate relationships. Many patients express fear of becoming pregnant and having children (4). JIA can cause patients to feel different from others, and negatively affect their self-esteem and body image. Good friendships and a sense of belonging to a social group are essential (4). Pain is a major factor during childhood and adolescence of patients with JIA, which can lead to absenteeism and decreased participation in activities. Patients with JIA have more anxiety and depression than healthy peers, which correlate with disability and active disease (8). Recent studies have reported that improvements in medications have been associated with decreased pain. However, patients often complain of the complicated and chronic medication regimen, the side effects, and the perceived lack of education regarding the medications. Individuals with JIA have expressed concern that JIA affected their relationships with siblings and worry that their parents do not receive enough outside support. Patients are also afraid of the future and how the disease will evolve (4).

A recent systematic review of qualitative studies revealed very invaluable insights into how children with JIA are coping and dealing with their chronic disease. One important insight was that children do not feel normal when they compare themselves to their peers. Children with JIA have to ask for help with certain tasks and feel that they are treated differently due to their disease if others around them are aware of it. They also feel that no one quite understands their disease or can even empathize with the unremitting pain that they suffer from on a regular basis. Physiatrists are adept at treating chronic pain and chronic diseases, which provides them ample experience that can be utilized in relating to children with JIA. Therefore, they can gain rapport with patients and their families by offering compassion and understanding of what the child with JIA has to endure (9).

Quality of life can be hindered in children with JIA. It was found that children with JIA desire to be active participants in their care and feel that health care professionals do not adequately explain the JIA disease process or even relay the reasoning behind why certain treatments were selected. Children with JIA are interested in being continually educated about all aspects of JIA including activity restrictions and therapy programs. Patients with JIA in general do not fully understand the benefits of exercise; therefore, it is vital to relay to patients and families that a therapy program as an outpatient or one instituted at home is necessary to alleviate joint stiffening and keeping joints at their optimum functioning. Physiatrists have the unique ability to work collaboratively with patients in designing an individualized strengthening and stretching therapy regimen that will lead to less pain, participation in more activities, and provide them with a sense that they have some control over certain aspects of their disease and bodies. It will also foster confidence and establish a strong patient and physician dynamic. Physiatrists and therapists can integrate child-friendly activities with a wide assortment of physical games into the patients’ therapy programs, so that patients are more likely to be compliant with their physical and occupational therapy plans (9).

It is important to be aware that JIA can decrease patients’ participation in school activities, hobbies, and jobs (4). Weiss et al. found that 30% of patients with JIA do not graduate from high school, and 30% are unemployed (8). Federal and state programs may provide assistance to children with JIA with school accommodations or services (Federal Act 504). The Juvenile Arthritis Alliance has resources related to education and vocation (7).

INJURIES ASSOCIATED WITH JIA

Patients with JIA have a higher fracture risk due to lower bone mass. Factors such as disease process, medication side effects, and physical inactivity combine to disrupt bone development and homeostasis. Long bones and vertebra are most at risk (10). Joint replacement surgeries may be needed in up to 72% of JIA patients, primarily those with the oligoarticular, polyarticular, and systemic subtypes. RF-positive patients have the greatest number of joint surgeries (8).

REHABILITATION OF THE PATIENT WITH JIA

JIA involves a cycle of symptoms that decrease physical activity, which in turn worsens the symptoms. Localized arthritis, decreased joint use, and glucocorticoid use all contribute to muscle atrophy. Children with JIA have reduced strength when compared to peers (11). Physical and occupational therapy can help maintain or increase joint ROM, reduce pain, and increase function strength and endurance. Gentle ROM, cold packs, heat, and appropriate rest during flares are key. ROM with passive extension more than flexion two to three times a day helps preserve joint ROM. Gentle relative rest helps decrease fatigue; resting in prone position helps decrease contractures from forming at the hip and knees.

Splinting can help with aligning during a flare-up. It provides local joint rest, supports weakened structures, and assists function. Heat helps in decreasing stiffness, increasing tissue elasticity, and decreasing pain and muscle spasm. Caution should be used while applying heat to insensate areas. Avoid heat during acute flare-ups. Avoid cold over insensate areas in patients with Raynaud phenomenon. Showers, heating pads, and paraffin baths are recommended, but ultrasound is avoided due to lack of evidence regarding growth plates. Custom splints may be needed to help prevent or slow joint tightening and/or deformities. School-based therapists can provide input on issues at school (7). Rehabilitation of JIA includes relative rest, splinting of joints as appropriate, maintaining ROM, use of modalities as tolerated, and socialization. Strengthening activities are important; swimming is a safe activity for children. Care has to be taken to minimize side effects like burns while using moist heat. Surgical correction of deformities or for conditions like avascular necrosis of the femoral neck should be followed by early rehabilitation with adequate pain control. Provision of assistive devices like a long-handled sponge and long-handled hairbrushes can make independence in day-to-day activities more manageable. Occupational therapists can help with school modifications like frequent rest breaks, having two sets of textbooks (one at home and one at school), reduced amount of writing, extra time to move between classes, note taker, and extra time to complete assignments. Vocational counseling after high school and college is critical for independence, education, and employment plans. Social work is valuable in ensuring coping strategies for patients and families in providing emotional and financial resources and helping transition of adolescents to adult status.

Exercise and Sports

Regular exercise ranging from low to high intensity has been shown to improve joint ROM, increase muscle strength, improve clinical symptoms, and improve health-related quality of life (11). In fact, studies show that exercise is a vital part of treatment in children with JIA. Inactivity decreases both aerobic and anaerobic capacities, and in combination with the disease can lead to deconditioning and further disability (6). Tai chi and yoga are recommended (6). Sports are not contraindicated, and participation in sports will not exacerbate the disease. Children with JIA can participate in any sport of interest, including impact activities and competitive contact sports, if their disease is well controlled and they have adequate physical capacity. Children with neck arthritis should have radiographic screening of atlantoaxial joints, with abnormal films needing further evaluation. Participation should be limited based on pain. As in the general population, children with JIA should wear appropriate protective equipment, including mouth guards and eye protection (12). Exercises in water showed benefits similar to those of land-based programs (13). It is very important to note that multiple studies have reported no adverse events related to exercise training (11).

MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

GOALS

Demonstrate knowledge of established and evolving biomedical, clinical epidemiological, and sociobehavioral sciences pertaining to JIA, as well as the application of this knowledge to guide holistic patient care.

OBJECTIVES

1. Describe the epidemiology, anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of JIA.

2. Discuss the seven subtypes of JIA and their characteristics.

3. Identify the pertinent laboratory and imaging studies important in JIA.

4. Review the treatment of JIA.

5. Recognize the complications and red flags associated with JIA.

6. Examine the ethical issues in JIA.

JIA is the most common rheumatic disease of childhood; 50% to 75% of patients seen in pediatric rheumatology referral clinics are due to JIA (1); 1 in 1,000 children is affected with JIA. Epidemiologic studies report the incidence of JIA from 1 to 22 per 100,000 with a prevalence of 8 to 150 per 100,000. European descent appeared to be an important predisposing factor for oligoarticular JIA; in addition, psoriatic JIA is also more common in patients of European descent. Black and Native American patients are more likely to have RF-positive polyarthritis. In general, girls are more often affected than boys. Females are more affected with oligoarticular and polyarticular JIA, and males are more affected with enthesitis-related JIA. Systemic subtype is relatively equal between the sexes. Age ranges of JIA development are median 5 to 8 years of onset, earliest with oligoarthritis and latest with seropositive polyarthritis (14).

JIA involves infiltration of the synovium by lymphocytes and macrophages with production of fibroblasts and macrophage-like synoviocytes. The anatomy of a growing child’s joint differs from that of adults. Children have thicker cartilage than adults due to ossification still being in progress; in addition, cartilage in children is able to renew itself better than in adults. Patients with JIA have been shown to improve radiographically with or even without treatment. Joint space narrowing is the most common form of radiographic damage in JIA (15).

The cause of JIA continues to remain inexact. JIA is hypothesized to be due to multifaceted genetic traits involved in immunity and inflammation that predispose one to develop JIA. When these genes are triggered by environmental factors such as stress, joint trauma, infection, or imbalanced hormones, then disease arises (8).

Particular human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I and class II alleles have been found to be linked to an increased risk of JIA. Inflammation also is involved. Serum levels of circulating immune complexes have been found in JIA, as have antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), C-reactive protein (CRP), and RF. Synovial fluid of JIA patients has revealed T cells and increased amounts of interleukins (15).

JIA, previously called juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, refers to a complex collection of rheumatologic disorders characterized by chronic arthritis and prolonged synovial inflammation that causes joint deterioration, thereby leading to diminished function and worsening of quality of life (15).

JIA is characterized by (1):

Arthritis for 6 weeks or longer in any one joint

Arthritis for 6 weeks or longer in any one joint

Onset age 16 years or less

Onset age 16 years or less

Diagnosis of exclusion

Diagnosis of exclusion

Patients have a similar set of complaints such as joint heat, joint pain, morning stiffness that improves throughout the day, “gelling phenomenon,” decreased ROM of a joint, and difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs) (1). The International League of Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) has set specific criteria for classification of JIA subtypes. There are 7 subtypes of juvenile arthritis: oligoarticular, polyarticular RF-positive, polyarticular RF-negative, systemic, enthesitis related, psoriatic, and “other” (15).

Oligoarticular JIA, the most common subtype of JIA, is characterized by arthritis in less than 5 large joints of the lower extremities during the first 6 months of disease. It is also possible for only one joint to be involved, which is most often the knee (1). Approximately 50% of patients with oligoarthritis JIA proceed to develop extended disease, and within a few years are afflicted with polyarticular JIA. Oligoarthritis JIA is the most common subtype associated with chronic uveitis (1,9–11). Other differential diagnoses should be considered if the patient displays a red and painful joint, hip involvement, systemic symptoms, refusal to bear weight, or if small joints are involved (1).

In polyarticular JIA, patients have five or more affected joints within the first 6 months of disease. Patients can have RF-negative and RF-positive diseases, and girls are more affected in general than boys. This subtype has no strong HLA association. The seronegative patients develop polyarticular JIA in early childhood. The seropositive polyarticular JIA patients are usually girls who develop severe erosive disease in late childhood and adolescence in symmetric pattern in small joints (14).

In systemic JIA, patients develop systemic extraarticular manifestations such as salmon-pink macular rash, 2 weeks of high-spiking twice-daily fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, pericardial effusions, and serositis. Patients then usually develop polyarticular joint involvement within 6 months of systemic symptoms. Uveitis is a very rare occurrence (8).

Enthesitis-related arthritis commonly involves the lower limbs, especially the hip. It is characterized by inflammation at the insertion of tendons, ligaments, or joint capsules such as bone iliac crest, posterior and anterior superior iliac spine, femoral greater trochanter, ischial tuberosity, patella, tibial tuberosity, Achilles, and plantar fascia insertion sites. It can also involve the sacroiliac joints (14).

In psoriatic JIA, psoriasis and arthritis may not occur at the same time. Positive laboratory markers include ANA and HLA-B27. Psoriatic arthritic JIA patients have asymmetric arthritis that can affect both large and small joints. If the rash is absent, then the diagnosis can be made if the patient has a family history of psoriasis in a first-degree relative, dactylitis, and nail pitting. These patients are at risk for iritis and need frequent ocular evaluations (14).

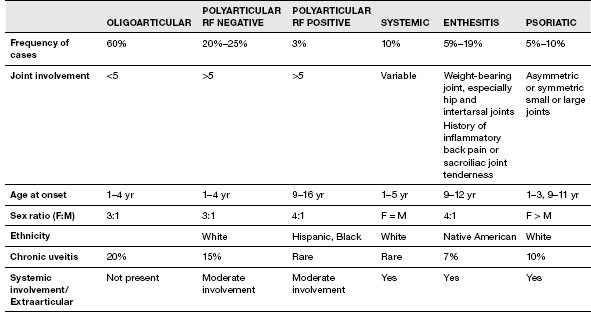

“Other” subtype includes children with symptoms that do not fall into any specific subtype or who have characteristics of more than one subtype of JIA (8). The characteristics of JIA subtypes are given in Table 31.1.

Diagnosis of JIA is based on patterns of clinical information and not solely on one particular imaging modality or diagnostic study. JIA is a diagnosis of exclusion and other possible causes need to be fully investigated. There is no specific laboratory test to definitively diagnose JIA. ESR is a nonspecific marker of inflammation and can be normal in patients with JIA. The majority of JIA patients are RF negative (95%) (1). RF can be positive in a number of conditions such as malignancy and is positive most commonly in viral infections. ANA can be positive in normal children. When ANA is positive in oligoarticular JIA, then the patient is at risk for ocular involvement. A very high ANA titer can indicate rheumatologic disease other than JIA, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Serial trending of inflammatory markers like CRP and ESR can help guide the effectiveness of medical management. Patients can also display hematologic abnormalities such as anemia of chronic disease and leukocytosis. Joint aspiration can be helpful in ruling out septic arthritis (15).

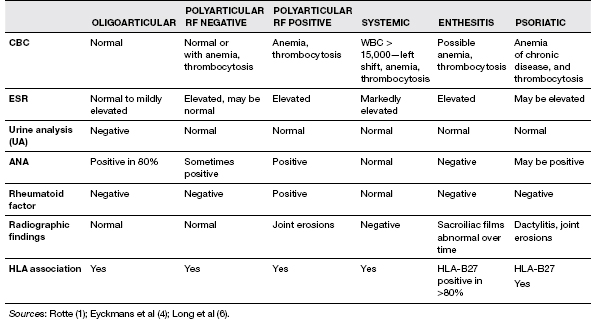

TABLE 31.1 Characteristics of JIA Subtypes

Ultrasonography is now being used more to evaluate joints in JIA. Advantages include noninvasiveness, capability to evaluate multiple joints, safety, and high tolerability among patients. It can be difficult to assess joints if the operator is not knowledgeable about ultrasound and certain joints cannot be visualized accurately. Ultrasonography may be used for identifying synovitis, subclinical synovitis, and cartilage; however, it may be avoided in children due to concern of damaging growth plates (18). It may not be as useful for enthesitis-related JIA, as ossification centers were incorrectly recognized as enthesitis on ultrasound. Continued research into MRI and ultrasonography is promising and will likely lead to earlier recognition of joint damage and prevention of disability (17) (Table 31.2).

Treatment involves a strategic approach that is centered on early intervention. Nonpharmacologic therapy such as occupational and physical therapy is essential to effectively treat JIA. Therapy programs focus on strength and stretching exercises, serial casting, splints, and orthotics, which are important tools in enhancing mobility, increasing ROM of joints, and avoiding joint contractures (19). Resting splints should be used at night only, because if used longer they can worsen joint stiffness. Splints should be evaluated by physiatrists at least twice a year as children grow frequently. Assistive devices like reachers and raised toilet seats are essential for JIA patients who have difficulty with ADLs. Modalities such as heat and cold are also used to help decrease pain and inflammation. Exercise has been shown to be helpful in achieving better function and aiding in quality of life for JIA patients (18). Adaptive strengthening exercises are important in play and day-to-day recreational activities. Isometric strengthening activities are allowed in acute flare-ups, with vigorous activities being embarked upon after the acute flare. Activities like swimming, dancing, noncontact karate, and Tai Chi are good options. Hydrotherapy with land-based therapies is helpful.

Ambulation should be promoted. Use of a posterior walker and a standing program are essential to the rehabilitation in JIA. A presurgical joint rehabilitation program focuses on strengthening muscles, training for future ambulation, and identifying other joints that may influence the rehabilitation process (Table 31.3).

Exercise prescription should include the type of exercise being recommended such as isometric versus isotonic; use of modalities (i.e., heat versus cold); precautions regarding falls, presence of contracture, atlantoaxial instability; duration of therapy (i.e., frequency and how many times a week); and evaluation for splints and adaptive equipments.

TABLE 31.2 Pertinent Laboratory and Imaging Findings in JIA Subtypes