ILAR criteria allow for uniform interpretation of clinical and therapeutic data. Recent validation of the ILAR classification criteria has found that 80% to 88% of children could be classified, and 12% to 20% were classified as “Undifferentiated” because they either did not fit into any category or fulfilled the criteria under two categories (9—12). As genetic risk factors and specific triggers of juvenile arthritis are identified, modifications to the criteria can be made. In the remaining sections of this chapter, the emphasis will be on the JIA classification scheme. The terms JRA and JCA will be used only when referring to specific epidemiologic, therapeutic, or outcome data.

TABLE 11-1 Comparison of JRA, JCA, and JIA Classifications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 11-2 Criteria for Classification of JIA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

than that seen in Europe. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear.

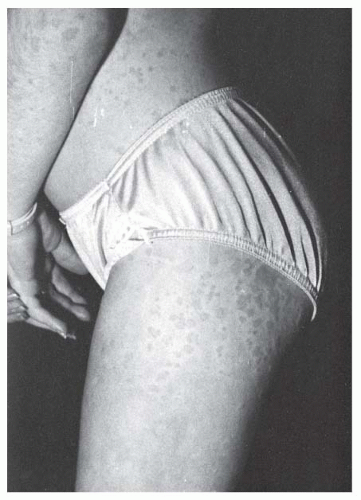

FIGURE 11-2. Juvenile psoriatic arthritis. A: Nail pitting associated with psoriasis. B: Swelling of a single DIP joint in a child with juvenile psoriatic arthritis. |

and arthropathy (SEA syndrome) who were shown to be at increased risk for development of classic spondyloarthritis or JAS (49, 50). ERA is defined as arthritis and enthesitis or arthritis or enthesitis with at least two of the following: (a) the presence or a history of sacroiliac (SI) tenderness or lumbosacral pain; (b) HLA-B27 antigen positivity; (c) onset of arthritis in a male after age of 6 years; (d) acute anterior uveitis; and (e) history of AS, ERA, sacroiliitis with IBD, reactive arthritis, or acute anterior uveitis in a first-degree relative. Exclusions for a diagnosis of ERA include (a) psoriasis or a history of psoriasis in the patient or a first-degree relative; (b) presence of IgM RF on at least two occasions, measured 3 months apart; and (c) systemic JIA.

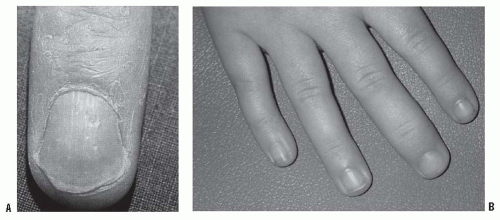

FIGURE 11-3. Achilles tendonitis and enthesitis in a child with enthesitis-related arthritis. (Courtesy of Dr. Ruben Burgos-Vargas.] |

TABLE 11-3 New York Criteria for AS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

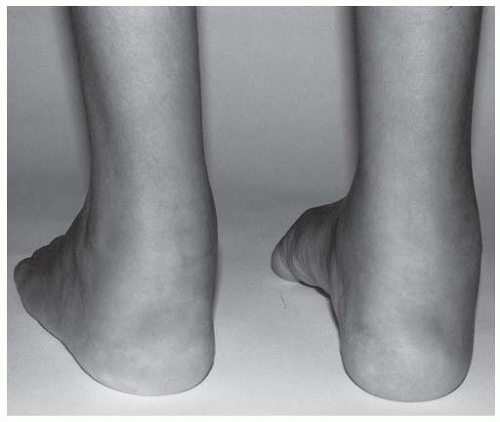

affecting predominantly the lower limb joints and entheses, is seen in 79% to 89.4%. These children tend to have fewer than 5 joints involved and rarely more than 10. At presentation, the pattern of involvement of the joints is usually asymmetric (61). Small joints of the toes are commonly involved in JAS but are seldom affected in other forms of JIA, with the exception of psoriatic arthritis. However, polyarticular and axial disease are usually evident after the 3rd year of illness (61). Children with long-standing JAS have been shown to develop tarsal bone coalition that has been termed ankylosing tarsitis (Fig. 11-4) (62).

FIGURE 11-4. Ankylosing tarsitis, a complex disorder resulting in ankylosis of the foot in a child with JAS. (Courtesy of Dr. Ruben Burgos-Vargas.) |

TABLE 11-4 Differential Diagnosis of JIA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

sexually active adolescent as an oligoarticular, polyarticular, or migratory arthritis with significant tenosynovitis.

FIGURE 11-5. Right knee effusion in a child with Lyme arthritis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|