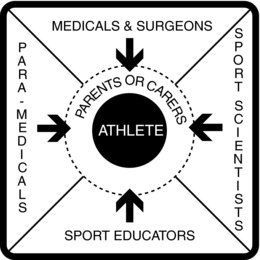

Figure 1.1 Diagram showing the breadth of sport injury management. Note that in the situation of an athlete who is a minor child, the parents or carers become part of the management scenario.

The British Association of Sport Rehabilitators and Trainers (BASRaT) administer the credential “Graduate Sport Rehabilitator,” which is abbreviated to “GSR.” According to this professional society, “a Graduate Sport Rehabilitator is a graduate level autonomous healthcare practitioner specialising in musculoskeletal management, exercise based rehabilitation and fitness” (British Association of Sport Rehabilitators and Trainers 2009b). Further, BASRaT outline the skill domains of a Graduate Sport Rehabilitator as being:

- professional responsibility and development

- prevention

- recognition and evaluation of the individual

- management of the individual–therapeutic intervention, rehabilitation and performance enhancement

- immediate care

Whilst prevention of injury is certainly desirable, the reality that athletes will be injured is part of sport participation. Thus, the sport rehabilitator must always be prepared to administer the care for which they are trained. The ideal place to begin providing this care is pitchside or courtside where the circumstances surrounding the injury have been observed and evaluation of the injury can be performed prior to the onset of complicating factors such as muscle spasm. Any sport rehabilitator who expects to offer this type of care must possess the proper qualification and additional credentials to support it. Minimum abilities include cardiopulmonary resuscitation, first aid, blood-borne pathogen safeguards, strapping and bracing, and practical experience (in a proper clinical education programme) with the variety of traumatic injuries that accompany sport participation. Furthermore, working with certain sports – such as cricket, ice hockey and North American football – requires specialised understanding of protective equipment that includes how to administer care in emergency situations when the injured athlete is encumbered by such equipment.

BASRaT’s (2009b) Role Delineation of the Sport Rehabilitator document details the implementation of the skill domains listed above into a scope of practice. Table 1.2 outlines the components of each domain; these are further subdivided into knowledge components and skill components to create a framework both for the education of sport rehabilitators and the extent of their capabilities to serve as healthcare professionals.

Table 1.2 Components of the British Association of Sport Rehabilitators and Trainers (2009b) skill domains

| Skill Domain | Components |

| Professional responsibility and development | Record keeping Professional practice – conduct and ethical issues Professional practice – performance issues |

| Prevention | Risk assessment and management Pre-participation screening Prophylactic interventions Health and safety Risks associated with environmental factors |

| Recognition and evaluation of the individual | Subjective evaluation Neuromusculoskeletal evaluation Physiological and biomechanical evaluation Nutritional, pharmacological, and psychosocial factors Health and lifestyle evaluation Clinical decision making Dissemination of assessment findings |

| Management of the individual – therapeutic intervention, rehabilitation and performance enhancement | Therapeutic intervention Exercise based rehabilitation Performance enhancement Factors affecting recovery and performance Monitoring Health promotion and lifestyle management |

| Immediate care | Emergency first aid Evaluation Initiation of care |

A brief introduction to a similar type of sport healthcare provider in the United States of America is useful here as a comparison. Certified Athletic Trainers (denoted by the qualification “ATC”) are “health care professionals who collaborate with physicians to optimize activity and participation of patients and clients. Athletic training encompasses the prevention, diagnosis, and intervention of emergency, acute, and chronic medical conditions involving impairment, functional limitations, and disabilities” (National Athletic Trainers’ Association 2009b). The National Athletic Trainers’ Association, the professional body of Certified Athletic Trainers, has existed since 1950. Standards of practice are set and a certification examination is administered by the Board of Certification (2009) to ensure that the profession is properly regulated. Most individual states in the USA also require possession of a licence in order to practice as an athletic trainer. Comparable to the role delineation skill domains for sport rehabilitators listed above, the requisite skills of Certified Athletic Trainers are categorised into 13 content areas (National Athletic Trainers’ Association 2009a):

1. foundational behaviours of professional practice

2. risk management and injury prevention

3. pathology of injuries and illnesses

4. orthopaedic clinical examination and diagnosis

5. medical conditions and disabilities

6. acute care of injuries and illnesses

7. therapeutic modalities

8. conditioning and rehabilitative exercise

9. pharmacology

10. psychosocial intervention and referral

11. nutritional aspects of injuries and illnesses

12. health care administration

13. professional development and responsibility

These content areas define how Certified Athletic Trainers are educated and how they retain the ATC credential via continuing professional development hours (called continuing education in the USA, with the participation increments called CEUs, or continuing education units). As with Graduate Sport Rehabilitators, accountability to such standards is imperative for sustaining the integrity of the profession.

Continuing professional development

There is no place pitchside for healthcare practitioners who cannot perform the required duties that arise under the pressure of managing injury during sporting competition. Therefore, a fundamental responsibility of the sport rehabilitator – or any other healthcare practitioner – is to secure a high standard in their education. Certainly this encompasses the undergraduate and postgraduate courses and the motivation to embrace diligence and excellence in all required modules, work placements, internships and the like. The knowledge required and tasks allowed for specific professional qualifications are usually dictated by professional organisations. As mentioned above, BASRaT hold sport rehabilitators to a high standard of education. Once a qualification is attained, however, another educational process ensues: professionals must engage in continuing professional development (CPD). The importance of this cannot be overstated. CPD helps the sport rehabilitator not only maintain their skills, but acquire new ones that broaden one’s ability to offer high quality healthcare to athletes, clients and patients. Moreover, knowledge in sport science and sport medicine is constantly evolving as further basic and applied research is undertaken. Adequate CPD helps the sport rehabilitator stay abreast of these developments.

CPD courses afford exciting opportunities for personal enrichment. Many topics are germane to the field and a veritable subculture exists to provide adequate chances for professionals to enlist in training courses that match every ability, need and desire. Most professional societies, including BASRaT, advise their members about suitable courses and the required quantity of CPD hours. Advanced life support, manual therapy, pitchside emergency care, strength training, exercise testing, specialised joint examinations, rehabilitative exercise and management of non-orthopaedic injuries and conditions are only a few topics representative of the wide gamut of offerings.

A qualification in basic cardiopulmonary resuscitation for healthcare providers (i.e. BLS/AED – Basic Life Support/Automated External Defibrillation) is considered a minimal credential that should be kept up to date by periodic skills retraining. The Resuscitation Council (UK) and the European Resuscitation Council publish the appropriate standards for BLS and AED training (European Resuscitation Council 2009; Resuscitation Council (UK) 2009); the latter also maintains a calendar of many life support courses offered around Europe, including the United Kingdom.

Knowledge, ability and wisdom

It is important for professional healthcare providers to distinguish amongst knowledge, ability and wisdom. These are distinct, yet interrelated, characteristics that all sport rehabilitators must strive for as they provide care to the public. Knowledge is the learning and understanding of facts that form the basis for practice. It provides the information on which a successful career is built. Ability is the application of knowledge. Thus, knowledge really is not useful until a person accomplishes a task by applying it.

Wisdom, though, is like the glue that holds a professional career together. It is the most difficult – but also the most significant – of the three to garner because it is gained over time as one matures and is exposed to an ever-widening variety of experiences. Wisdom considers both the available knowledge and ability, mixing them in the right proportion to elicit the best result within a given set of present circumstances. Whilst this may seem somewhat esoteric, the three characteristics are fundamental to success and all healthcare professionals draw on each of them everyday.

Ethical considerations

Ethics refers to a set of concepts, principles and laws that inform people’s moral obligation to behave with decency. Part of this is the necessity to protect people who are in a relatively vulnerable position, such as a patient or client in a healthcare setting. Similar to other professionals, each sport rehabilitator must consider themselves a healthcare practitioner and, therefore, under an ethical obligation for inscrutable professional conduct. Sport medicine presents challenging parameters within which to apply an ethical framework (Dunn et al. 2007; Salkeld 2008), due largely to the high public visibility of sport itself. This is perhaps an even more significant reason for the sport rehabilitator to ardently ensure that their practice falls under appropriate accountability.

Unfortunately ethical dilemmas do not always lend themselves to clear, objective dispensation; thus, governing bodies codify guiding principles for conduct. The Code of Ethics of the British Association of Sport Rehabilitators and Trainers, shown in Table 1.3, is an example of guidelines that promote proper behaviour.

Table 1.3 The Code of Ethics of the British Association of Sport Rehabilitators and Trainers (2009a)

| PRINCIPLE 1: Members shall accept responsibility for their scope of practice |

| 1.1 Members shall not misrepresent in any manner, either directly or indirectly, their skills, training, professional credentials, identity or services 1.2 Members shall provide only those services of assessment, analysis and management for which they are qualified and by pertinent legal regulatory process 1.3 Members have a professional responsibility to maintain and manage accurate medical records 1.4 Members should communicate effectively with other healthcare professionals and relevant outside agencies in order to provide an effective and efficient service to the client Supporting Legislation: Data Protection Act 1998; Human Rights Act 1998 |

| PRINCIPLE 2: Members shall comply with the laws and regulations governing the practice of musculoskeletal management in sport and related occupational settings |

| 2.1 Members shall comply with all relevant legislation 2.2 Members shall be familiar with and adhere to all British Association of Sport Rehabilitators and Trainers’ Guidelines and Code of Ethics 2.3 Members are required to report illegal or unethical practice detrimental to musculoskeletal management in sport and related occupational settings |

| PRINCIPLE 3: Members shall respect the rights, welfare and dignity of all individuals |

| 3.1 Members shall neither practice nor condone discrimination on the basis of race, creed, national origin, sex, age, handicap, disease entity, social status, financial status or religious affiliation. Members shall comply at all times with relevant anti-discriminatory legislation 3.2 Members shall be committed to providing competent care consistent with both the requirements and limitations of their profession 3.3 Members shall preserve the confidentiality of privileged information and shall not release such information to a third party not involved in the client’s care unless the person consents to such release or release is permitted or required by law |

| PRINCIPLE 4: Members shall maintain and promote high standards in the provision of services |

| 4.1 Members shall recognise the need for continuing education and participation in various types of educational activities that enhance their skills and knowledge 4.2 Members shall educate those whom they supervise in the practice of musculoskeletal management in sport and related occupational settings with regard to the code of ethics and encourage their adherence to it 4.3 Whenever possible, members are encouraged to participate and support others in the conduct and communication of research and educational activities, that may contribute to improved client care, client or student education and the growth of evidence-based practice in musculoskeletal management in sport and related occupational settings 4.4 When members are researchers or educators, they are responsible for maintaining and promoting ethical conduct in research and education |

| PRINCIPLE 5: Members shall not engage in any form of conduct that constitutes a conflict of interest or that adversely reflects on the profession |

| 5.1 The private conduct of the member is a personal matter to the same degree as is any other person’s, except when such conduct compromises the fulfillment of professional responsibilities 5.2 Members shall not place financial gain above the welfare of the client being treated and shall not participate in any arrangement that exploits the client 5.3 Members may seek remuneration for their services that is commensurate with their services and in compliance with applicable law |

In healthcare the field of ethics sets appropriate and acceptable standards to protect the public from damages incurred at the hands of unscrupulous or incompetent practitioners and the deleterious effects of unwarranted or dangerous diagnostic or therapeutic interventions. Respect for the dignity of humans is placed foremost and healthcare practice must accommodate to this high standard. There are a number of circumstances that occur in sport that can strain the typical application of ethics; areas where difficulties arise include:

- decisions about return to sport activity with a persisting injury

- pharmaceutical therapies to assist participation

- participation of children, especially in high-risk sport

- sharing of confidential athlete medical information amongst practitioners, or between practitioners and public representatives, such as the press

- ergogenic aids, such as anabolic steroids and blood “doping.”

Of these, treating an athlete’s medical information with confidentiality is likely to be the most difficult and frequently compromised, particularly in the pitchside environment (Salkeld 2008). Salkeld suggests that several competing challenges and pressures collide pitchside to create ethical dilemmas: the close proximity of an injured player to other players and coaches when being examined, the public visibility of an injury, the interests of the sporting club and the desire of the coaching staff to receive information about the injury coupled with the concomitant desire of the player to shield this information from the coaches. Additional areas of contemporary ethical challenges for practitioners caring for athletes include informed consent for care, drug prescription and use of innovative or emerging technologies (Dunn et al. 2007).

The most appropriate way for the sport rehabilitator to manage potentially difficult ethical predicaments is to practise diligently under an approved ethical code, such as that of the British Association for Sport Rehabilitators and Trainers, and to decide how individual ethical quandaries will be handled prior to being confronted by them. The consequences of infractions are severe and have resulted in revoked professional licences, registrations and certifications, and have ended careers in particularly egregious cases.

Legal considerations

An additional concern when providing care to athletes is the increasingly litigious aura that pervades much of Western society. Sport rehabilitators and other practitioners of sport injury care are subject to lawsuits brought by athletes and their representatives (e.g. parents, carers). As previously mentioned, consistently following an appropriate code of ethics and continually educating yourself via CPD are two ways to ameliorate the risk. It is also crucial that sport injury professionals maintain malpractice and liability insurance cover, a caveat for which BASRaT ensures compliance of its member Graduate Sport Rehabilitators.

The discussion of legal liability first needs a directive citing the proper way of acting that is acknowledged by courts when deriving judgments. “The man on the Clapham omnibus” is a common phrase in English law that denotes a person who acts truly and fairly (Glynn and Murphy 1996) with all faculties that would be expected under the circumstances. (An American equivalent is “a reasonable and prudent person.”) A structure of accountability is fundamental to application of this concept. Within a given context it may be modified appropriately; healthcare is only one realm to which it pertains (Glynn and Murphy 1996). Whilst being afraid of the potential for litigation in a sport healthcare environment would unnecessarily constrain a well-qualified professional, undeniably sport rehabilitators and other healthcare practitioners must be cognisant of the inherent risk of being sued for wrong actions (acts of commission) or for inaction when action is warranted (acts of omission). Instead of being intimidated, one should take all necessary steps to reduce the likelihood of a lawsuit as much as possible.

The tenet of a “public right to expertise” was proposed for the sport and physical education fields more than 25 years ago (Baker 1980, 1981). The general concept states that members of the public have the right to expect that those who offer themselves as professionals in a given field of endeavour are qualified as experts in that field. In the context of sport rehabilitation, affording the public this right is paramount because of the potential for severe consequences when healthcare providers are inadequately skilled or make errors in practice or judgement (Goodman 2001).

Countless legal cases transcend recent decades (Appenzeller 2005) as plaintiffs (people filing a lawsuit) persist in claiming negligence by defendants (people being sued) such as healthcare providers, coaches and institutions. Generally a negligence claim must show the following (Champion 2005):

- there is a verifiable standard of care to which the defendant should be held

- the defendant had a duty to care for the plaintiff

- the defendant breached their duty

- the plaintiff sustained damages or injury

- the damages or injury were caused by the defendant’s breach of the duty.

Risk of exposure to legal liability related to healthcare in sport usually occurs in four main areas, the first three of which are related to one another (Kane and White 2009):

1. Pre-participation physical examination – A screening process to evaluate the athlete’s physical and mental status prior to engaging in sport should be a fundamental requirement before such engagement occurs.

2. Determination of an athlete’s ability to participate – Whether confronted with signs and symptoms pitchside, courtside, in a first aid facility, in a polyclinic, or elsewhere, proper decision making about an athlete’s fitness to participate must be made in accordance with current healthcare practice.

3. Evaluation and care of significant injuries on the pitch or court – Healthcare professionals not only must be well-qualified, they must deliver care that is appropriate for a given situation. Concussions, spinal cord injuries and hyperthermia are three examples of injuries requiring urgent, specialised diagnostic and treatment procedures. A sponsoring club, university, school or organisation must ensure that a plan is in place to adequately respond to emergency situations that may arise in sport.

4. Disclosure of personal medical record information – Confidentiality is a fundamental right and expectation of all patients and clients, including athletes. The sport rehabilitator must take care to not convey – even unwittingly – information about an athlete’s case to others without the athlete’s permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree