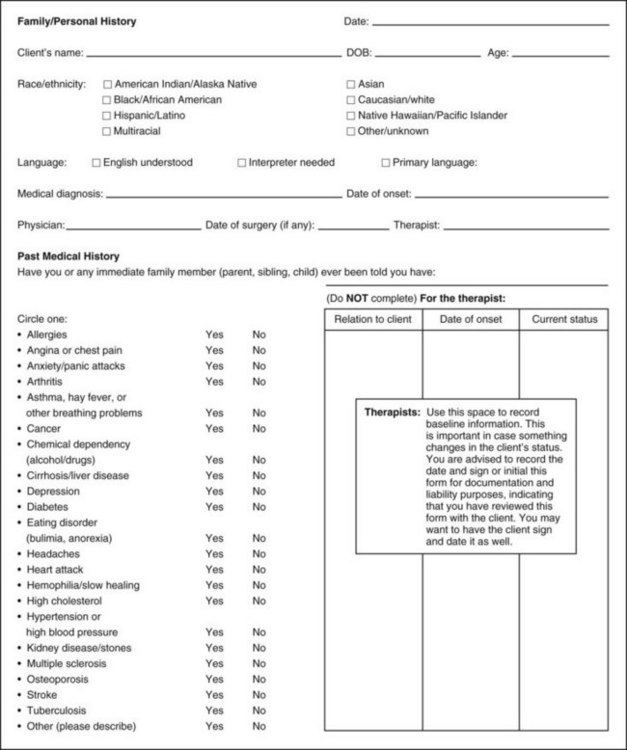

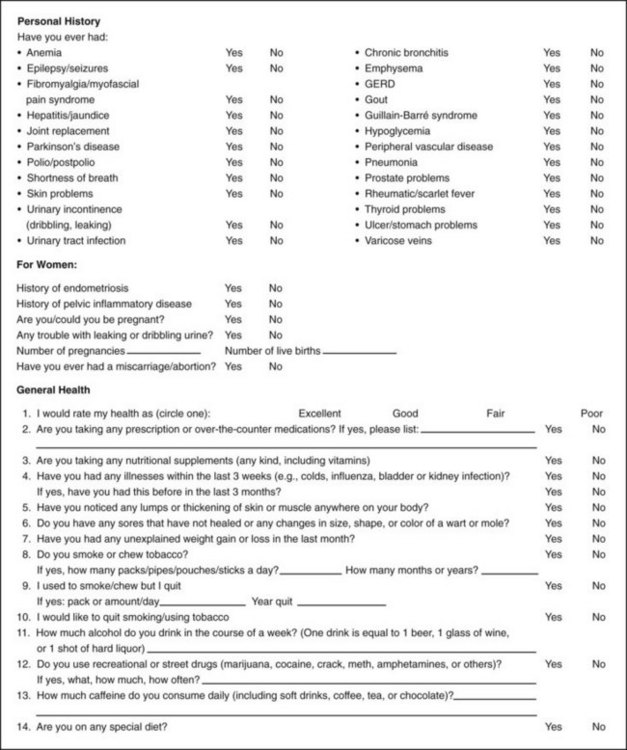

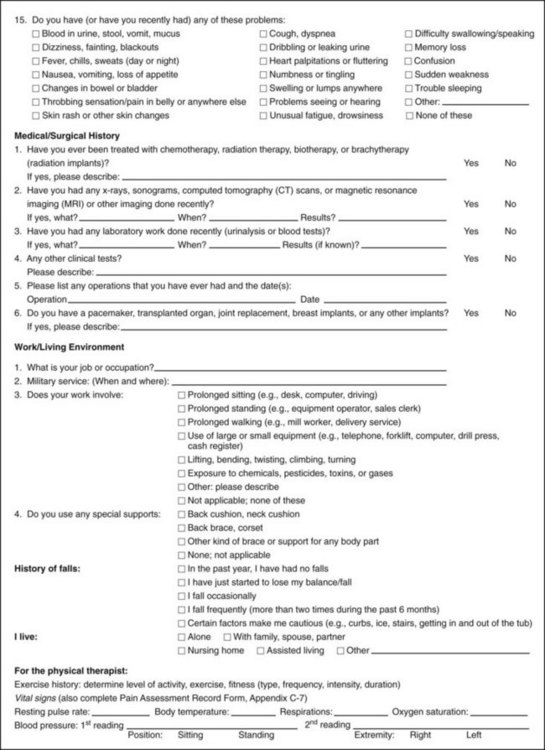

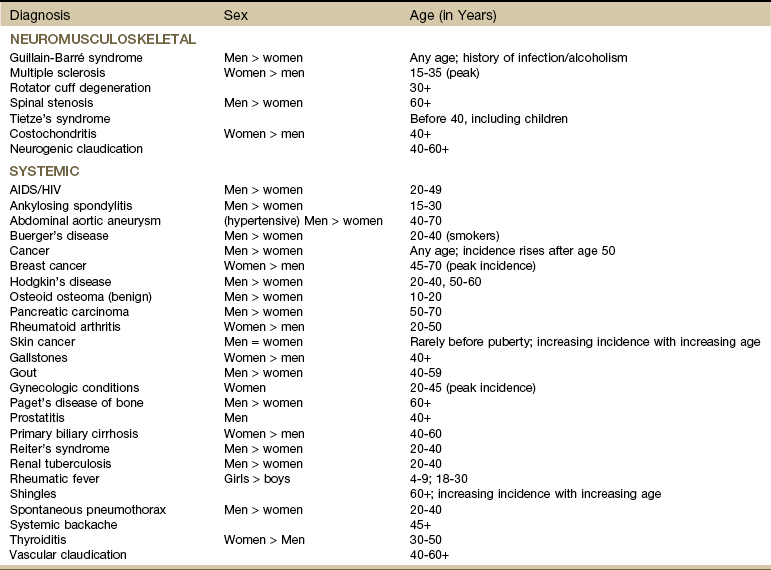

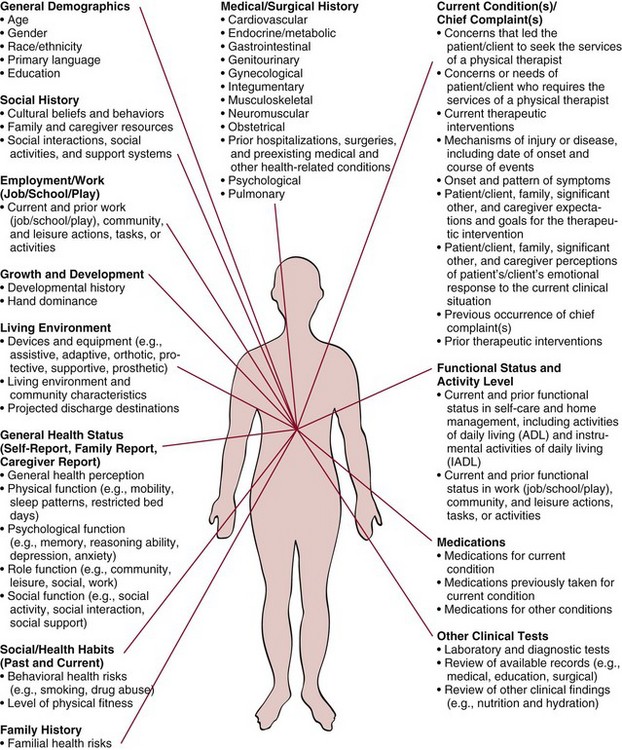

Chapter 2 Interviewing is a skill that requires careful nurturing and refinement over time. Even the most experienced health care professional should self-assess and work toward improvement. Taking an accurate medical history can be a challenge. Clients’ recollections of their past symptoms, illnesses, and episodes of care are often inconsistent from one inquiry to the next.1 Clients may forget, underreport, or combine separate health events into a single memory, a process called telescoping. They may even (intentionally or unintentionally) fabricate or falsely recall medical events and symptoms that never occurred. The individual’s personality and mental state at the time of the illness or injury may influence their recall abilities.1 Compassion is the desire to identify with or sense something of another’s experience and is a precursor of caring. Caring is the concern, empathy, and consideration for the needs and values of others. Interviewing clients and communicating effectively, both verbally and nonverbally, with compassionate caring takes into consideration individual differences and the client’s emotional and psychologic needs.2,3 Relying on one interviewing style may not be adequate for all situations. There are cultural differences based on family of origin or country of origin, again for both the therapist and the client. In addition to spoken communication, different cultural groups may have nonverbal, observable differences in communication style. Body language, tone of voice, eye contact, personal space, sense of time, and facial expression are only a few key components of differences in interactive style.4 Nearly 24 million people in the United States do not speak or understand English. More than one third of English-speaking patients and half of Spanish-speaking patients at U.S. hospitals have low health literacy.5 According to the findings of the Joint Commission, health literacy skills are not evident during most health care encounters. Clear communication and plain language should become a goal and the standard for all health care professionals.6 Low health literacy means that adults with below basic skills have no more than the most simple reading skills. They cannot read a physician’s (or physical therapist’s) instructions or food or pharmacy labels.7 Low health literacy translates into more severe, chronic illnesses and lower quality of care when care is accessed. There is also a higher rate of health service utilization (e.g., hospitalization, emergency services) among people with limited health literacy. People with reading problems may avoid outpatient offices and clinics and utilize emergency departments for their care because somebody else asks the questions and fills out the form.7 We are living at a time when the amount of health information available to us is almost overwhelming, and yet most Americans would be shocked at the number of their friends and neighbors that (sic) can’t understand the instructions on their prescription medications or how to prepare for a simple medical procedure.8,9 The therapist must keep in mind that many people in the United States speak English as a second language (ESL) or are limited English proficient (LEP), and many of those people do not read, or write English.10 More than 14 million people age 5 and older in the United States speak English poorly or not at all. Up to 86% of non–English speakers who are illiterate in English are also illiterate in their native language. Although the percentages of illiterate African-American and Hispanic adults are much higher than those of white adults, the actual number of white nonreaders is twice that of African-American and Hispanic nonreaders, a fact that dispels the myth that literacy is not a problem among Caucasians.11 Watch for behavioral red flags such as misspelling words, not completing intake forms, leaving the clinic before completing the form, outbursts of anger when asked to complete paperwork, asking no questions, missing appointments, or identifying pills by looking at the pill rather than naming the medication or reading the label.12 The IOM has called upon health care providers to take responsibility for providing clear communication and adequate support to facilitate health-promoting actions based on understanding. Their goal is to educate society so that people have the skills they need to obtain, interpret, and use health information appropriately and in meaningful ways.13,14 Therapists should minimize the use of medical terminology. Use simple but not demeaning language to communicate concepts and instructions. Encourage clients to ask questions and confirm knowledge or tactfully correct misunderstandings.13 Consider including the following questions: There is a text available specifically for physical therapists to help us identify our own culture and recognize the importance of understanding and communicating with clients of different cultural backgrounds. Widely accepted cultural practices of various ethnic groups are included along with descriptions of cultural and language nuances of subcultures within each ethnic group.15 A text on this same topic for health care professionals is also available.16 Identifying individual personality style may be helpful for each therapist as a means of improving communication. Resource materials are available to help with this.17,18 The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a widely used questionnaire designed to identify one’s personality type, is also available on the Internet at www.myersbriggs.org. For the experienced clinician, it may be helpful to reevaluate individual interviewing practices. Making an audio or videotape during a client interview can help the therapist recognize interviewing patterns that may need to improve. Watch and/or listen for any of the guidelines listed in Box 2-1. Texts are available with the complete medical interviewing process described. These resources are helpful not only to give the therapist an understanding of the training physicians receive and methods they use when interviewing clients, but also to provide helpful guidelines when conducting a physical therapy screening or examination interview.19,20 The therapist should be aware that under federal civil rights laws and the Medicaid Act, any client with LEP has the right to an interpreter free of charge if the health care provider receives federal funding. But keep in mind that quality of care for individuals who are LEP is compromised when qualified interpreters are not used (or available). Errors of omission, false fluency, substitution, editorializing, and addition are common and can have important clinical consequences.10 Standards for medical interpreting professionals in the United States have been published and are available online.21 The Joint Commission’s 2007 report, What did the doctor say? Improving health literacy to protect patient safety, is a must read. It is available online at www.jointcommission.org. Interviewing and communication require a certain level of cultural competence as well. Culture refers to integrated patterns of human behavior that include the language, thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions of racial, ethnic, religious, or social groups.2,22 Multiculturalism is a term that takes into account that every member of a group or country does not have the same ideals, beliefs, and views. Cultural competence can be defined as the ability to understand, honor, and respect the beliefs, lifestyles, attitudes, and behaviors of others.23 Cultural competency goes beyond being “politically correct.” As health care professionals, we must develop a deeper sense of understanding of how ethnicity, language, cultural beliefs, and lifestyles affect the interviewing, screening, and healing process. The need for culturally competent physical therapy care has come about, in part, because of the rising number of groups in the United States. Groups other than “white” or “Caucasian” counted as race/ethnicity by the U.S. Census are listed in Box 2-2. Previously these groups were referred to as “minorities,” but social scientists are looking for a different term to describe these groups. Terms such as “dominant” and “nondominant” have been suggested when discussing race and ethnicity. This has come about because some minority groups are no longer a “minority” in the United States due to changing demographics. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 31% of the U.S. population belongs to a racial/ethnic minority group. By the year 2042, Caucasians will represent less than 50% of the population (currently at approximately 75%).24 Hispanic Americans will comprise nearly a quarter of the American population (currently 12.5% and expected to reach 30% by 2042). African Americans make up 12.5% of the population (as of 1990). This will increase to approximately 15% so that Hispanic Americans will outnumber African Americans by 2 : 1. Asian/Pacific Island Americans will make up almost 10% in 2050.24 Clients from a racial/ethnic background may have unique health care concerns and risk factors. It is important to learn as much as possible about each group served (Case Example 2-1). Clients who are members of a cultural minority are more likely to be geographically isolated and/or underserved in the area of health services. Risk-factor assessment is very important, especially if there is no primary care physician involved. Cultural factors can affect the way a person follows through on instructions, interprets questions, and participates in his or her own care. In addition to the guidelines in Box 2-1, Box 2-3 offers some “Dos” in a cultural context for the physical therapy or screening interview. Learning about cultural preferences helps therapists become familiar with factors that could impact the screening process. More information on cultural competency is available to help therapists develop a deeper understanding of culture and cultural differences, especially in health and health care.4,25,26 The Health Policy and Administration Section of the APTA has a Cross-Cultural & International Special Interest Group (CCISIG) with information available regarding international physical therapy, international health-related issues, and physical therapists working in third world countries or with ethnic groups.27 The APTA also has a department dedicated to Minority and International Affairs with additional information available online regarding cultural competence.23,36 Information on laws and legal issues affecting minority health care are also available. Best practices in culturally competent health services are provided, including summary recommendations for medical interpreters, written materials, and cultural competency of health professionals.36 The APTA’s Tips to Increase Cultural Competency offers information on values and principles integral to culturally competent education and delivery systems, a Publications Corner that includes articles on cultural competence, links to resources, resources for treating patients/clients from diverse background, and more.28 Also, there is a Blueprint for Teaching Cultural Competence in Physical Therapy Education now available that was created by the Committee on Cultural Competence.29 This program is a guide to help physical therapists develop core knowledge, attitudes, and skills specific to developing cultural competence as we meet the needs of diverse consumers and strive to reduce or eliminate health disparities.29 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health has published national standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) in health care. These are available on the Office of Minority Health’s Web site (www.omhrc.gov/clas).30 Resources on the language and cultural needs of minorities, immigrants, refugees, and other diverse populations seeking health care are available, including strategies for overcoming language and cultural barriers to health care.31 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons offers a free online mini-test of cultural competence for residents and medical students that physical therapist may find helpful and informative.32 For more specific information about the Muslim culture, visit The Council on American-Islamic Relations33 or the Muslim American Society.34,35 The Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA) offers publications on professional competencies in providing a safe clinical environment for Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender-Intersex (LGBTI) health.37 The therapist will use two main interviewing tools during the screening process. The first is the Family/Personal History form (see Fig. 2-2). With the client’s responses on this form and/or the client’s chief complaint in hand, the interview begins. The overall client interview is referred to in this text as the Core Interview (see Fig. 2-3). The Core Interview as presented in this chapter gives the therapist a guideline for asking questions about the present illness and chief complaint. Screening questions may be interspersed throughout the Core Interview as seems appropriate, based on each client’s answers to questions. The most basic skills required for a physical therapy interview include: Beginning an interview with an open-ended question (i.e., questions that elicit more than a one-word response) is advised, even though this gives the client the opportunity to control and direct the interview.38 People are the best source of information about their own condition. Initiating an interview with the open-ended directive, “Tell me why you are here” can potentially elicit more information in a relatively short (5- to 15-minute) period than a steady stream of closed-ended questions requiring a “yes” or “no” type of answer (Table 2-1).39,40 This type of interviewing style demonstrates to the client that what he or she has to say is important. Moving from the open-ended line of questions to the closed-ended questions is referred to as the funnel technique or funnel sequence. TABLE 2-1 Each question format has advantages and limitations. The use of open-ended questions to initiate the interview may allow the client to control the interview (Case Example 2-2), but it can also prevent a false-positive or false-negative response that would otherwise be elicited by starting with closed-ended (yes or no) questions. Follow-Up Questions: The funnel sequence is aided by the use of follow-up questions, referred to as FUPs in the text. Beginning with one or two open-ended questions in each section, the interviewer may follow up with a series of closed-ended questions, which are listed in the Core Interview presented later in this chapter. Pain assessment is often a central focus of the therapist’s interview, so for the clinician interested in quantifying pain, some way to quantify and describe pain is necessary. There are numerous pain assessment scales designed to determine the quality and location of pain or the percentage of impairment or functional levels associated with pain (see further discussion in Chapter 3). Some tools focus on a particular kind of problem such as activity limitations or disability in people with low back pain (e.g., Oswestry Disability Questionnaire,41 Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale,42 Duffy-Rath Questionnaire).43 The Simple Shoulder Test44 and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH)45 may be used to assess physical function of the shoulder. Nurses often use the PQRST mnemonic to help identify underlying pathology or pain (see Box 3-3). Other examples of specific tests include the • Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; see Figure 3-6) • Verbal Descriptor Scale (see Box 3-1) • McGill Pain Questionnaire (see Fig. 3-11) • Pain Impairment Rating Scale (PAIRS) A more complete evaluation of client function can be obtained by pairing disease- or region-specific instruments with the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36 Version 2).46,47 The SF-36 is a well-established questionnaire used to measure the client’s perception of his or her health status. It is a generic measure, as opposed to one that targets a specific age, disease, or treatment group. It includes eight different subscales of functional status that are scored in two general components: physical and mental. An even shorter survey form (the SF-12 Version 2) contains only 1 page and takes about 2 minutes to complete. There is a Low-Back SF-36 Physical Functioning survey48 and also a similar general health survey designed for use with children (SF-10 for children). All of these tools are available at www.sf-36.org. To see a sample of the SF-36 v.2 go to www.sf-36.org/demos/SF-36v2.html. The initial Family/Personal History form (see Fig. 2-2) gives the therapist some idea of the client’s previous medical history (personal and family), medical testing, and current general health status. Make a special note of the box inside the form labeled “Therapists.” This is for liability purposes. Anyone who has ever completed a deposition for a legal case will agree it is often difficult to remember the details of a case brought to trial years later. Resources: The Family/Personal History form presented in this chapter is just one example of a basic intake form. See the companion website for other useful examples with a different approach. If a client has any kind of literacy or writing problem, the therapist completes it with him or her. If not, the therapist goes over the form with the client at the beginning of the evaluation. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice49 provides an excellent template for both inpatient and outpatient histories (see the Guide, Appendix 6). Other commercially available forms have been developed for a wide range of prescreening assessments.50 The Review of Systems (see Box 4-19; see also Appendix D-5), which provides a helpful chart of signs and symptoms characteristic of each visceral system, can be used along with the Family/Personal History form. The Guide also provides both an outpatient and an inpatient documentation template for similar purposes (see the Guide, Appendix 6). A teaching tool with practice worksheets is available to help students and clinicians learn how to document findings from the history, systems review, tests and measures, problems statements, and subjective and objective information using both the SOAP note format and the Patient/Client Management model shown in Fig. 1-4.51 The subjective examination must be conducted in a complete and organized manner. It includes several components, all gathered through the interview process. The order of flow may vary from therapist to therapist and clinic to clinic (Fig. 2-1). Fig. 2-1 Types of data that may be generated from a client history. In this model, data about the visceral systems is reflected in the Medical/Surgical history. The data collected in this portion of the patient/client history is not the same as information collected during the Review of Systems (ROS). It has been recommended that the ROS component be added to this figure.52 (From Guide to physical therapist practice, ed 2 [Revised], Alexandria, VA, 2003, American Physical Therapy Association.) The Family/Personal History form presented here (Fig. 2-2) is one example of an initial intake form. Throughout the rest of this chapter, the text discussion will follow the order of items on the Family/Personal History form. The reader is encouraged to follow along in the text while referring to the form. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has developed a computerized tool to help people learn more about their family health history. “My Family Health Portrait” is available online at: www.hhs.gov/familyhistory/download.html. Conversely, a woman with no history of trauma but with a previous history of breast cancer who is self-referred to the therapist without a previous medical examination and who complains of shoulder pain should be interviewed more thoroughly. The simple question “How will the answers to the questions I am asking permit me to help the client?” can serve as your guide.53 It is helpful to be aware of NMS and systemic conditions that tend to occur during particular decades of life. Signs and symptoms associated with that condition take on greater significance when age is considered. For example, prostate problems usually occur in men after the fourth decade (age 40+). A past medical history of prostate cancer in a 55-year-old man with sciatica of unknown cause should raise the suspicions of the therapist. Table 2-2 provides some of the age-related systemic and NMS pathologic conditions. Epidemiologists report that the U.S. population is beginning to age at a rapid pace, with the first baby boomers turning 65 in 2011. Between now and the year 2020, the number of individuals age 65 and older (referred to by some as the “Big Gray Wave”) will double, reaching 70.3 million and making up a larger proportion of the entire population (increasing from 13% in 2000 to 20% in 2030).54 Dementia increases the risk of falls and fracture. Delirium is a common complication of hip fracture that increases the length of hospital stay and mortality. Older clients take a disproportionate number of medications, predisposing them to adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, poor adherence to medication regimens, and changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics related to aging.55,56

Interviewing as a Screening Tool

Concepts in Communication

Compassion and Caring

Communication Styles

Illiteracy

English as a Second Language

The Physical Therapist’s Role

Resources

Cultural Competence

Minority Groups

Cultural Competence in the Screening Process

Resources

The Screening Interview

Interviewing Techniques

Open-Ended and Closed-Ended Questions

Open-Ended Questions

Closed-Ended Questions

1. How does bed rest affect your back pain?

1. Do you have any pain after lying in bed all night?

2. Tell me how you cope with stress and what kinds of stressors you encounter on a daily basis.

2. Are you under any stress?

3. What makes the pain (better) worse?

3. Is the pain relieved by food?

4. How did you sleep last night?

4. Did you sleep well last night?

Interviewing Tools

Subjective Examination

Key Components of the Subjective Examination

Family/Personal History

Resources

Follow-Up Questions (FUPs)

Age and Aging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Interviewing as a Screening Tool