Intertrochanteric Hip Fractures: The Sliding Hip Screw

Kenneth A. Egol

INTRODUCTION

Hip fractures in the elderly are associated with significant morbidity and mortality and will continue to burden the health care system as the population continues to age (1). Intertrochanteric hip fractures represent approximately half of the fractures that occur in the proximal femur, with a strong female preponderance throughout all age groups (2). Mortality rates for extracapsular hip fractures are comparable with those of femoral neck fractures, with 1-year mortality rate of 20% to 30%.

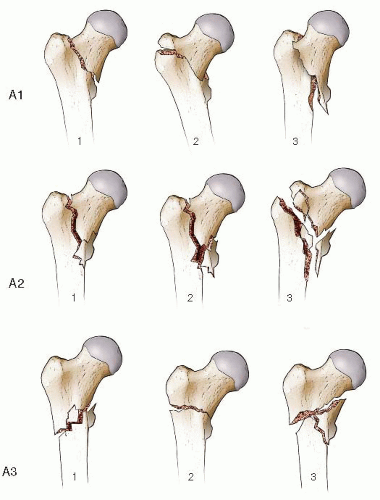

While several classification systems exist, intertrochanteric fractures are best classified as stable or unstable based upon the integrity of the posteromedial cortex. The Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) classification is useful both to determine the stability of the fracture pattern and to guide treatment (4). Intertrochanteric fractures are classified as 31-A fractures and further subdivided into 31-A1, 31-A2, and 31-A3 fractures (Fig. 17.1). The 31-A1 simple fracture is a stable fracture with a single fracture line extending along the intertrochanteric line (A1.1), through the greater trochanter (A1.2), or below the lesser trochanter (A1.3). The 31-A2 fracture is multifragmentary and is subdivided into progressively more unstable patterns with a loss of medial support: A2.1 fractures are simple fractures with one additional fragment, progressing to several fragments (A2.2) and fracture extension >1 cm below the lesser trochanter (A2.3). Most A2 fractures are considered unstable with the exception of the 31-A2.1 pattern. In the most unstable pattern, 31-A3, the fracture enters the lateral cortex of the femur distal to the vastus ridge. This pattern can manifest as a reverse oblique intertrochanteric fracture (A3.1), a simple transverse fracture (A3.2), or a multifragmentary fracture (A3.3).

ANATOMICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The intertrochanteric region of the hip is the area between the greater and lesser trochanters and represents a zone of transition from the femoral neck to the femoral shaft. This area is characterized primarily by dense trabecular bone that serves to transmit and distribute stress, similar to the cancellous bone of the femoral neck. The orientation of the trabeculae in the intertrochanteric and greater trochanteric region acts to resist highly compressive forces (5). The greater and lesser trochanters are the sites of insertion of the major muscles of the gluteal region: the gluteus medius and minimus, the iliopsoas, and short external rotators. The calcar femorale, a vertical wall of dense bone extending from the posteromedial aspect of the femoral shaft to the posterior portion of the femoral neck, forms an internal trabecular strut within the inferior portion of the femoral neck and intertrochanteric region and acts as a strong conduit for transfer of load. This region is extracapsular and is less prone to many of the healing complications seen with femoral neck fractures.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Virtually all patients who sustain an intertrochanteric hip fracture with any displacement should be considered for surgical repair. The goals of treatment are stable internal fixation of the fracture that will allow early mobilization and protected weight bearing with uncomplicated healing. Patient factors that are important in the decision-making process are associated with medical comorbidities, preinjury level of function, and bone quality.

Extremely frail patients deemed too “sick” for surgery or who were nonambulatory prior to their fracture may be treated nonoperatively with a short period of bed rest and gradual mobilization to a chair. Bone quality may also affect the surgeon’s choice of implant (nail vs. plate) or the length or the device. In a small group of patients with symptomatic preexisting hip arthritis or severe osteoporosis due to systemic medical condition such as renal failure or metastatic disease may be candidates for primary hip arthroplasty instead of fracture fixation.

Extremely frail patients deemed too “sick” for surgery or who were nonambulatory prior to their fracture may be treated nonoperatively with a short period of bed rest and gradual mobilization to a chair. Bone quality may also affect the surgeon’s choice of implant (nail vs. plate) or the length or the device. In a small group of patients with symptomatic preexisting hip arthritis or severe osteoporosis due to systemic medical condition such as renal failure or metastatic disease may be candidates for primary hip arthroplasty instead of fracture fixation.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

History and Physical Examination

The vast majority of hip fractures occur in the elderly following a fall from standing height. Geriatric hip fracture management requires a treatment algorithm that takes into account the complex medical and social needs of this patient population. Patients with multiple medical problems pose a dilemma. Many of these patients are taking anticoagulation medication that must be reversed prior to surgery. In a small but substantial number of patients, a cardiac, neurological, or metabolic event was the inciting event that led to the fall. Consultation with specialists in internal medicine, cardiology, pulmonary, etc., is frequently required. Surgery should be performed as soon as it is safe but often requires 24 to 48 hours of medical optimization.

On physical examination, the affected leg is usually shortened and externally rotated. There is marked tenderness to palpation around the hip and proximal thigh. Any movement of the limb is painful and resisted by the patient. The neurovascular status of the extremity should be carefully assessed and documented.

Imaging Studies

An anteroposterior (AP) pelvis and an AP and lateral radiograph of the hip should be obtained in all patients with a suspected hip injury. This usually allows the physician to establish the diagnosis; however, important details regarding the fracture geometry may be difficult to interpret if the x-rays were obtained with the leg shortened and externally rotated. If there is any doubt about the fracture morphology, a traction radiograph with the leg internally rotated should be obtained. This should be done with appropriate analgesia in the radiology suite or in the operating room prior to surgery.

In patients with no obvious fracture following a mechanical fall, the x-rays should be scrutinized for a pelvic ring injury or an occult femoral neck fracture. If none are identified and the patient is unable to bear weight, a CT scan or MRI should be obtained. Bone scans are rarely used.

Timing of Surgery

Most patients with an intertrochanteric hip fracture should have surgery when medically optimized, if possible within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. These injuries are deemed urgent rather than emergent. Surgery is best done during the daytime or evening and late night surgery is rarely indicated. Early surgery avoids the problems of prolonged recumbency and minimizes the risk of decubiti, atelectasis, urinary tract infections, pulmonary infections, and thrombophlebitis, which can be fatal in the frail geriatric patient. Prompt medical and anesthesia consultation also facilitate timely surgery. Occasionally, surgery must be delayed beyond 24 hours due to severe medical comorbidities. Patients who are admitted over the weekend with a hip fracture should not wait until Monday for their procedure to be completed for surgeon convenience.

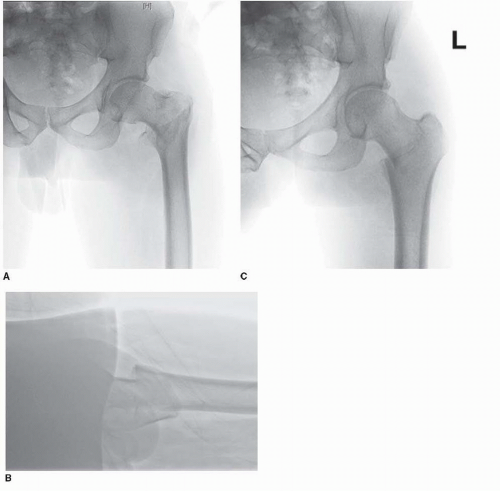

Surgical Tactic

There are two main categories of implants that are used in the treatment of intertrochanteric fractures: the cephalomedullary nail and the sliding hip screw and side plate (6, 7, 8, 9 and 10). There is a large body of literature that supports the use of a sliding hip screw for stable intertrochanteric fracture patterns (Fig. 17.2). On the other hand, several randomized controlled trials support the use of both an intramedullary nail and a hip screw in unstable fracture patterns. The one fracture where the use of a sliding hip screw is contraindicated is a reverse obliquity fracture pattern due to the risk of excessive shortening and medialization of the shaft postoperatively. This fracture pattern is more appropriately treated with a cephlomedullary implant or fixed angle implant.

FIGURE 17.2 A stable intertrochanteric hip fracture. A. AP radiograph. B. Cross-table lateral radiograph. C. Traction/internal rotation view. |

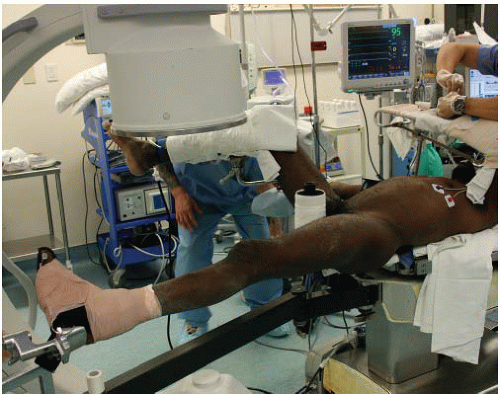

FIGURE 17.3 Positioning with the unaffected limb in the “well leg” holder in the lithotomy position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|