Intertrochanteric Fractures

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Intertrochanteric fractures account for nearly 50% of all fractures of the proximal femur.

There are approximately 150,000 intertrochanteric fractures annually in the United States with an annual incidence of 63 and 34 per 100,000 population per year for elderly females and males, respectively.

The ratio of women to men ranges from 2:1 to 8:1, likely because of postmenopausal metabolic changes in bone.

Some of the factors associated with intertrochanteric rather than femoral neck fractures include advancing age, increased number of comorbidities, increased dependency in activities of daily living, and a history of other osteoporosis-related (fragility) fractures.

ANATOMY

Intertrochanteric fractures occur in the region between the greater and lesser trochanters of the proximal femur, occasionally extending into the subtrochanteric region.

These extracapsular fractures occur in cancellous bone with an abundant blood supply. As a result, nonunion and osteonecrosis are less problematic than in femoral neck fractures.

Deforming muscle forces will usually produce shortening, external rotation, and varus position at the fracture.

Abductors tend to displace the greater trochanter laterally and proximally.

The iliopsoas displaces the lesser trochanter medially and proximally.

The hip flexors, extensors, and adductors pull the distal fragment proximally.

Fracture stability is determined by the presence of posteromedial bony contact, which acts as a buttress against fracture collapse.

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Intertrochanteric fractures in younger individuals are usually the result of a high-energy injury such as a motor vehicle accident or fall from a height.

Ninety percent of intertrochanteric fractures in the elderly result from a simple fall.

Most fractures result from a direct impact to the greater trochanteric area.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

It is the same as for femoral neck fractures (see Chapter 29).

Patients may have experienced a delay before hospital presentation. This time is usually spent on the floor and without oral intake. The examiner must therefore be cognizant of potential dehydration, nutritional depletion, venous thromboembolic disease (VTE), and pressure ulceration issues as well as hemodynamic instability because intertrochanteric fractures may be associated with as much as a full unit of hemorrhage into the thigh.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

An anteroposterior (AP) view of the pelvis and an AP and a crosstable lateral view of the involved proximal femur are obtained.

A physician-assisted internal rotation view of the injured hip may be helpful to clarify the fracture pattern further.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently the imaging study of choice in delineating nondisplaced or occult fractures that are not apparent on plain radiographs. Bone scans or computed tomography (CT) scanning is reserved for those who have contraindications to MRI.

CLASSIFICATION

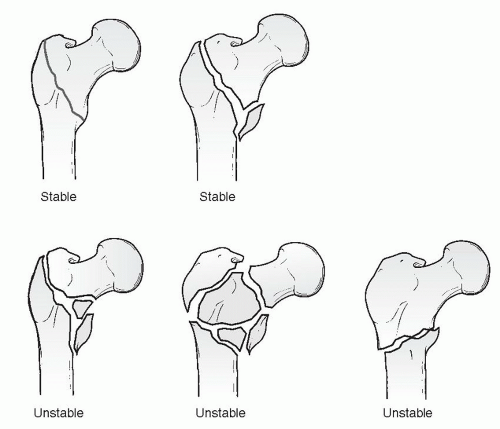

Evans (Fig. 30.1)

This is based on prereduction and postreduction stability, that is, the convertibility of an unstable fracture configuration to a stable reduction.

In stable fracture patterns, the posteromedial cortex remains intact or has minimal comminution, making it possible to obtain and maintain a stable reduction.

Unstable fracture patterns are characterized by greater comminution of the posteromedial cortex. Although they are inherently unstable, these fractures can be converted to a stable reduction if medial cortical opposition is obtained.

The reverse obliquity pattern is inherently unstable because of the tendency for medial displacement of the femoral shaft.

The adoption of this system was important not only because it emphasized the important distinction between stable and unstable fracture patterns but also because it helped define the characteristics of a stable reduction.

Orthopaedic Trauma Association Classification of Intertrochanteric Fractures

See Fracture and Dislocation Classification Compendium at http://www.ota.org/compendium/compendium.html.

Several studies have documented poor reproducibility of results based on the various intertrochanteric fracture classification systems.

Many investigators simply classify intertrochanteric fractures as either stable or unstable, depending on the status of the posteromedial cortex. Unstable fracture patterns comprise those with comminution of the posteromedial cortex, subtrochanteric extension, or a reverse obliquity pattern.

UNUSUAL FRACTURE PATTERNS

Basicervical Fractures

Basicervical neck fractures are located just proximal to or along the intertrochanteric line (Fig. 30.2).

Although anatomically femoral neck fractures, basicervical fractures are usually extracapsular and thus behave and are treated as intertrochanteric fractures.

They are at greater risk for osteonecrosis than the more distal intertrochanteric fractures.

They lack the cancellous interdigitation seen with fractures through the intertrochanteric region and are more likely to sustain rotation of the femoral head during implant insertion.

Reverse Obliquity Fractures

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree