Metastatic bone lesions involving the distal femur are less frequently encountered than those affecting the pertrochanteric region or diaphysis. While only 4% of all metastatic bone lesions ultimately result in pathologic fracture, those affecting the femur may portend a seven- to eightfold increased risk, particularly those resulting from primary breast carcinoma.

The goal of treatment is to provide immediate fracture stability, allowing for rapid patient mobilization and full weight-bearing with return to function. Patients with distal femoral metastasis may seek medical attention prior to pathologic fracture, and in such cases, nonoperative management may be a reasonable alternative to surgical intervention if symptoms and osseous stability permit.

Patients presenting after fracture through a metastatic lesion, however, are rarely treated nonoperatively. The results of nonoperative treatment in this patient population are less than optimal, leading to decreased mobility, prolonged hospital stays, and increased risk of pulmonary and cardiovascular complications. Depending on the histology of the lesion, the presence of metastatic lesions involving other organ systems, and the patient’s overall health, median life-expectancy may range anywhere from 6 months to >48 months, and the surgeon should assume that the patient may not survive long enough for the fracture to heal. As a consequence, the initial surgical stabilization of the fracture should be adequate to provide immediate weight bearing. If adequate stability cannot be achieved by internal fixation alone or supplementation with polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement, an alternative treatment option should be employed, such as prosthetic distal femoral replacement.

Patients at risk of pathologic fracture are generally treated according to fracture risk. The most common method of determining the likelihood of fracture is the use of a popular classification system described by Mirels (

1). Nonoperative management typically consists of external beam radiotherapy, hormone therapy, and/or the administration of bisphosphonates. This regimen, while effective, is generally more successful in non-weight-bearing portions of the appendicular skeleton, such as the distal upper extremity.

Nonoperative treatment of patients with a symptomatic lesion of the distal femur, or those who have already sustained a pathologic fracture, however, is less likely to result in effective pain control or adequate function. For this subset of patients, internal fixation with or without PMMA augmentation provides reliable pain relief and rapid mobilization (

2). Various authors have advocated en bloc resection of solitary lesions resulting from primary thyroid and renal cell carcinoma (

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9). Althausen et al. (

3) cited presentation with a long disease-free interval between nephrectomy and first metastases and appendicular skeletal location as favorable prognostic factors (

3). The authors advocate aggressive surgical resection rather than internal fixation in such cases.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Treatment of metastatic lesions resulting in pathologic fracture of the distal femur must be individualized. Relative contraindications to open reduction and internal fixation include

Life expectancy <3 months

Active infection

Acute deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (placement of a vena caval filter may be considered preoperatively in certain cases)

Severely compromised bone quality proximal or distal to the level of fracture.

Additionally, in cases of severe fracture comminution, extremely poor bone quality, or extensive neurovascular envelopment, outcomes may be compromised (

10).

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

A comprehensive review of the preoperative evaluation and preparation of patients with metastatic lesions to the distal femur is provided elsewhere (

11) In general, patients should undergo a thorough preoperative medical evaluation, including history and physical examination as well as laboratory evaluation. Physical examination should focus on ruling out concomitant lesions that may affect treatment options, carefully inspecting the skin and surrounding soft tissues, and performing a complete neurovascular evaluation. In addition, the examination of the patient without a history of metastatic disease should include palpation of the thyroid, breast, and prostate as potential sites of primary carcinoma (

12).

Investigations

For those patients presenting with a pathologic fracture as the initial symptom of metastatic disease, the workup should include laboratory analysis (including complete blood count, liver enzymes, alkaline phosphatase, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and serum protein electrophoresis), chest radiograph, whole body technetium-99m-phosphate scintigraphy, and computed tomography of the chest abdomen and pelvis. This protocol has been shown to identify 85% of primary lesions (

12). Attention should also be paid to the patient’s overall nutritional status and healing potential.

Adjuvant Therapy

Perioperative treatment with bisphosphonates decreases the incidence of pathologic fracture secondary to metastasis (

13). Radiation therapy is also employed postoperatively to reduce pain and obtain local control of microscopic disease (

14). Radiation therapy is generally delayed until the wound has adequately healed, typically 2 to 4 weeks postoperatively.

If surgery is to be delayed more than 24 to 72 hours, placement of a simple bridging external fixator will prevent fracture shortening, and may also be used as an aid to reduction at the time of definitive fixation. The surgeon should make every effort to avoid placement of the fixator in a location that would compromise future skin incisions. A simple frame can be constructed with two 4.5-mm half pins in the anterior femur, and two 4.5-mm half pins into the medial tibial shaft.

Classification

In general, fractures of the distal femur are classified from high-quality anteroposterior and lateral radiographs alone. Occasionally, however, it is necessary to obtain specialized views or further imaging. Traction views are particularly helpful if there is a high degree of comminution, or if there exists ligamentous involvement resulting in a significant sagittal deformity. Computed tomography scans are also used liberally for fractures that extend to the articular surface. Magnetic resonance imaging can also be helpful to determine the extent of disease, although hematoma makes interpretation difficult once a fracture has occurred. Advanced imaging often helps delineate those patients with disease too extensive for open reduction alone and may help determine the need for prosthetic replacement.

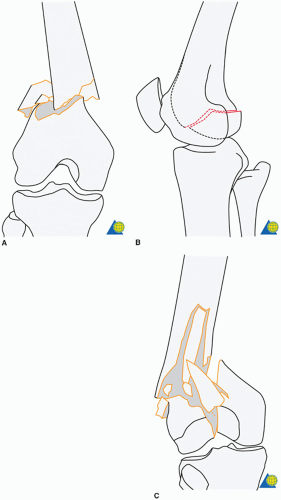

Various classification systems are available that describe fractures of the distal end of the femur. The most common classification currently used is that of Reudi et al. (

Fig. 22.1;

Table 22.1) Type A fractures involve the extra-articular aspect of the distal femur only and are subclassified according to the amount of comminution present. Type B fractures consist of simple articular fragments, medial, lateral, and coronal (also referred to as the Hoffa fragment). Type C fractures are characterized by involvement of both the metaphyseal and intraarticular aspect of the distal femur.

Utilizing a preoperative templating system as described by the AO Group is extremely useful for planning the intraoperative sequence of fixation, particularly when dealing with pathologic fractures due to metastatic lesions. The mental exercise of formulating an operative plan allows the surgeon to anticipate intraoperative problems before they occur. Templating each individual screw will alert the surgeon to areas that are likely to gain poor purchase into the pathologic bone and potentially require supplemental fixation with PMMA cement.

Multiple fixation devices, including 95-degree fixed-angle plates, retrograde or antegrade femoral nails, and locked plates, should be available at the time of surgery. The advantages and disadvantages of each are explained in

Table 22.1. In general, pathologic fractures are more effectively treated with load-sharing devices such as intramedullary nails, to allow for immediate weight-bearing with less concern for hardware failure. In some cases, however, such as very distal fractures, or those with a high degree of intra-articular involvement, a plate and screw construct is preferable. Plates are also indicated when the intramedullary canal is already occupied by another device, which is quite common in patients with established metastatic disease.

Biopsy

The need for histologic confirmation of solitary lesions prior to surgical stabilization cannot be overemphasized (

12,

14,

15). It is estimated that primary sarcomas may account for up to 10% to 20% of solitary lesions in patients with a history of previously treated malignancy (

16). If the surgeon is unsure of the correct diagnosis, needle or open biopsy prior to internal fixation is an effective means of histologic confirmation. As noted above, treatment of solitary metastasis from renal or thyroid carcinoma with en bloc resection may result in improved patient life expectancy, even in the face of existing pulmonary metastasis. Consultation with an orthopedic oncologist is recommended if wide resection is potentially indicated or a solitary lesion exists (

Fig. 22.2).

Informed Consent

Prior to any surgical procedure, the surgeon should have an open discussion about the various treatment options with the patient. The surgeon should set realistic expectations, and it should be explained that prosthetic replacement is a possibility if adequate stabilization cannot be obtained intraoperatively. Prior to any attempt at internal fixation of a pathologic distal femur fracture, the surgeon should be prepared to abort the

procedure and proceed with prosthetic replacement if he or she does not feel comfortable allowing the patient to immediately weight-bear on the construct. The goal of internal fixation in these cases is to return the patient to preinjury function as soon as possible and to provide excellent pain relief for the remainder of the patient’s life. As a general rule, the surgeon should leave the operating room under the assumption that the fracture will never heal (

15).