Chapter 8 Internal Derangements

Menisci and Cartilage

Meniscus

Anatomy

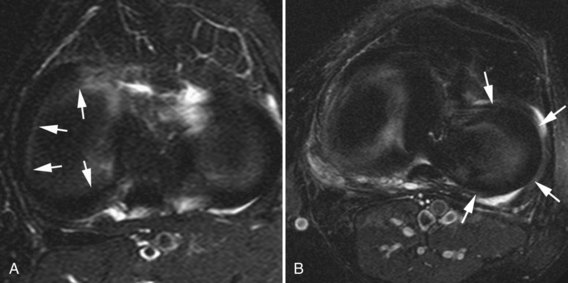

Both menisci are thicker in craniocaudad dimension along the periphery and taper to a thinner margin along the free edge. Although the medial and lateral menisci serve the same purpose in the medial and lateral compartments of the knee, they are not symmetrical in size or shape. The medial meniscus is a larger C-shaped structure, and the lateral meniscus is a tighter, near complete circle (Fig. 8-1). Because of these morphologic differences, the medial meniscus covers approximately one half of the tibial plateau contact surface, and the lateral meniscus covers approximately three quarters of the tibial plateau contact surface.

The medial meniscus can be differentiated from the lateral meniscus by position and size, and also by its distinct morphologic characteristics and regional attachments. The posterior horn of the medial meniscus is wider in an anteroposterior dimension than the anterior horn. This can be demonstrated on sagittal imaging of the knee when the posterior horn appears two to three times larger than the anterior horn (Fig. 8-2). The posterior horn of the medial meniscus attaches to the tibia at the posterior intercondylar fossa, anterior to the posterior cruciate ligament insertion, but behind the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus. The anterior horn of the medical meniscus attaches to the tibia at the anterior intercondylar fossa, in front of both the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus and the insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament. The periphery of the medial meniscus is attached to the joint capsule along its entire length via meniscotibial and coronary ligaments.12

In comparison, the lateral meniscus is symmetrical from front to back (Fig. 8-3). Therefore, on sagittal imaging of the knee, the posterior horn and the anterior horn are similar in size. The posterior horn of the lateral meniscus attaches to the tibia behind the intercondylar eminence, anterior to both the posterior cruciate ligament insertion and the posterior horn of the medial meniscus. The anterior horn of the lateral meniscus attaches to the tibia in front of the intercondylar eminence, behind both the anterior horn of the medial meniscus and the anterior cruciate ligament insertion. The fibers of the anterior cruciate ligament partially blend with the lateral meniscus at its tibial attachment. The periphery of the lateral meniscus cannot attach directly to the joint capsule because of the intra-articular course of the popliteus tendon between the lateral meniscus and the joint capsule. The lateral meniscus actually attaches to the joint capsule through small fascicles or struts.

Function

The menisci have many biomechanical functions. They act to increase contact area and joint congruity, transmit load and absorb shock, prevent radial extrusive forces during axial loading, and aid in joint lubrication. Because fibrocartilage is less stiff than hyaline cartilage, the menisci intrinsically have a higher shock-absorbing capacity. Functional meniscal studies have found that 50% to 85% of the load placed across the joint is transmitted by the meniscus. Following total meniscectomy, the contact area between the femur and the tibia decreases by approximately 75%; thus contact stresses between the femur and the tibia increase by more than 200%. Studies have demonstrated that contact stresses at the knee joint proportionately increase in relation to the amount of meniscus removed.12

MRI Criteria for Meniscal Injuries

In this study, 100% correspondence was noted between MRI grade signal alteration and histologic grade. MRI grade 1 and 2 signal alterations corresponded with meniscal degeneration. MRI grade 3 signal alteration corresponded with meniscal tear.20

Later it was described that as the number of sequential images with abnormal surfacing meniscal signal increased, the accuracy of diagnosing a meniscal tear also increased. In two separate studies conducted in 1993 and 2005, the positive predictive value for diagnosing meniscal tears increased when two or more images with surfacing signal abnormality were required compared with only a single abnormal image.8 This concept was presented as the two-slice-touch rule and is used by many radiologists today in diagnosing meniscal tear.

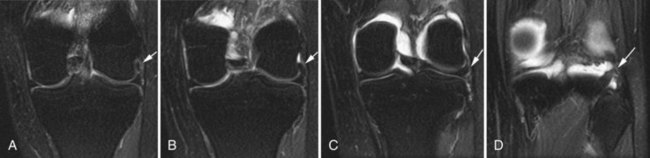

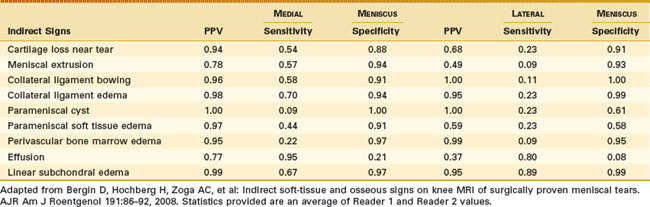

Secondary signs of meniscal tear can enhance confidence in diagnosis, particularly in cases where the signal abnormality within the meniscus is equivocal, or when the study is degraded by artifact. Indirect evidence of meniscal pathology includes adjacent cartilage loss, parameniscal cyst (also referred to as meniscal cyst), meniscal extrusion, parameniscal soft tissue edema, bowing of the ipsilateral collateral ligament, joint effusion, perivascular bone marrow edema, and subchondral bone marrow edema (Table 8-1).1

Table 8-1 Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Sensitivity, and Specificity of Indirect Signs for Meniscal Tears at Arthroscopy

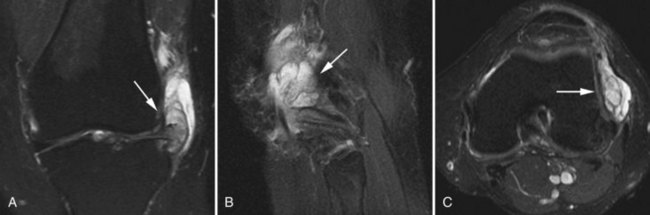

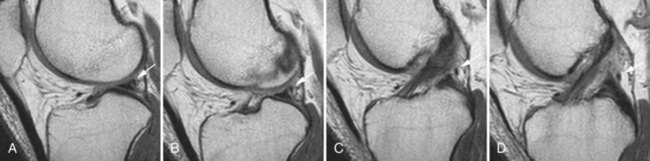

The presence of a parameniscal cyst has a 100% positive predictive value for an associated meniscal tear in some studies. Parameniscal cysts are believed to result from extruded joint fluid through an adjacent meniscal tear.2 Parameniscal cysts are seen in 7% of meniscal tears (Fig. 8-4). They have the same incidence for medial and lateral meniscal tears but are seen more commonly medially owing to higher prevalence of medial tears. Medial meniscal cysts are most frequently located posteriorly, and lateral meniscal cysts are most frequently located anteriorly.2

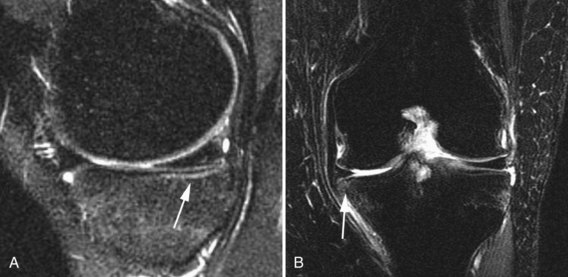

Adjacent collateral ligament edema and linear subchondral bone marrow edema have been shown to have high specificity and positive predictive values in the diagnosis of meniscal tear.1 Collateral ligament edema can be seen in the setting of primary ligamentous injury and osteoarthritis. However in the setting of meniscal tear, collateral ligament edema likely reflects inflammatory hyperemia, reactive synovitis, and increased fluid formation related to the tear (Fig. 8-5). The sensitivity of this sign is greater for medial meniscal tears, indicating the closer apposition of the medial collateral ligament to the periphery of the medial meniscus as compared with the lateral collateral ligament and the lateral meniscus. Periarticular bone marrow edema can be seen with trauma and osteoarthritis. However, in the setting of meniscal tear, linear subchondral bone marrow edema is located directly adjacent to the meniscus and probably represents hyperemia at the junction of the bony cortex, cartilage, and meniscus (Fig. 8-6). These secondary signs can help guide attention to the meniscus on MRI and can increase confidence when primary diagnostic criteria are equivocal.1

Meniscal extrusion can also be used as a secondary sign of meniscal tear. It is defined as extension of the peripheral meniscus past the tibial margin, and it results from a tear that destabilizes the circumferential collagen fibers of the meniscus and allows it to expand in a radial direction (Fig. 8-7). Major meniscal extrusion (>3 mm) is more highly associated with extensive tears, advanced meniscal degeneration, complex tears, and large radial tears. Tears that extend into the meniscal root are also more likely to result in substantial meniscal extrusion. Identifying meniscal extrusion is important, not only in the detection of meniscal tear, but also because it is strongly associated with the development of osteoarthritis.3,13

Errors in Interpretation

Some normal variants may cause confusion in the diagnosis of meniscal tears. For instance, the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus can have a speckled appearance with foci of increased signal. This may be related to blending of the fibers of the anterior cruciate ligament with the anterior horn, or splaying of the fibers of the meniscus at its attachment.11 This abnormal signal should not be mistaken for a tear or degeneration (Fig. 8-8).

Meniscal flounce is a rare normal variant of the medial meniscus in which there is an undulating appearance of the inner margin, possibly related to ligamentous laxity (Fig. 8-9). This buckling along the free edge may be confused for a meniscal tear, but is not said to increase the risk of tearing. Its prevalence is approximately 0.2%.11

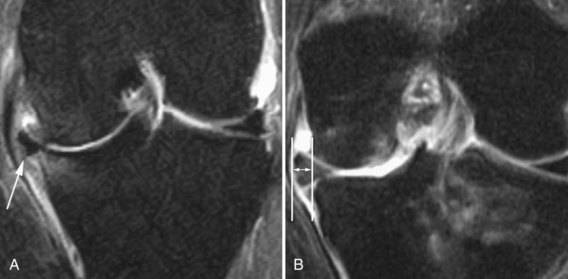

The meniscofemoral ligaments of Wrisberg and Humphrey connect the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus to the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. The ligament can divide and course anterior to the posterior cruciate ligament named the ligament of Humphrey, or posterior to the posterior cruciate ligament named the ligament of Wrisberg (Fig. 8-10). The ligaments of Humphrey and Wrisberg are noted in approximately one third of cases. If soft tissue or fluid is interposed between the origin of the meniscofemoral ligament and the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus, this interface can be misinterpreted as a meniscal tear. Care must be taken to follow the ligament over several successive images while avoiding this pitfall.15

The transverse intermeniscal ligament courses horizontally between the anterior horns of the medial and lateral menisci, in front of the anterior cruciate ligament. The interface between the ligament and the anterior meniscal horns can also be confused for a tear.15

The popliteus tendon travels superiorly from its muscle belly in an oblique, intra-articular course, separating the lateral meniscus from the joint capsule, to insert on the popliteal groove along the lateral aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. The popliteal bursa is the opening created by the fascicles of the lateral meniscus, which allow the popliteal tendon to course from its muscle belly into its intra-articular location, and finally to insert on the femur. The medial margin of the popliteal hiatus is the body of the lateral meniscus (Fig. 8-11). Fluid within the popliteus tendon sheath or the popliteal hiatus may be mistaken for a meniscal tear.7,23

A meniscal contusion occurs during an acute traumatic event, typically described with an acute anterior cruciate ligament disruption. The meniscus is compressed between the femur and the tibia, becomes contused, and demonstrates altered signal on MRI. The increased signal within the contused meniscus is more likely to be amorphous in shape, will not extend to the articular surface, and may be accompanied by a bone bruise. This may simulate a meniscal tear and result in a false-positive MRI interpretation.11

Magic angle phenomenon describes the artifact that occurs when collagen fibers are oriented at 55 degrees relative to the main magnetic field on short TE images. This artifact causes falsely increased signal intensity and can imitate a meniscal tear. This is particularly a dilemma in the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus as it angles upward from its root to the insertion on the tibia behind the intercondylar eminence.6

Chondrocalcinosis within the fibrocartilage of the meniscus can cause a false-positive interpretation for tear. Chondrocalcinosis results in increased signal on proton density and T1-weighted images, which can be confused with a meniscal tear.11 Correlation with radiographs may help to detect and confirm the presence of chondrocalcinosis within the meniscus (Fig. 8-12).

Some authors propose that a delay between MRI diagnosis of meniscal tear and arthroscopy may allow for spontaneous healing.17 When the tear is not identified at surgery, it is documented as a false positive. Others report that healed or surgically repaired meniscal tears may have persistent signal that extends to the articular surface and can be mistaken for a new meniscal tear or retear. Some meniscal tears are more difficult to visualize at arthroscopy, particularly along the inferior surface of the medial meniscus.7 If these tears are not documented by arthroscopy, which is the gold standard, then they are also reported as false positive.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree