1.4 Interdependence of Posture and the Pelvic Floor

What does posture have to do with the pelvic floor? Posture appears to be something external and visible, while the pelvic floor muscles lie deep in the center of the body, palpable but not visible.

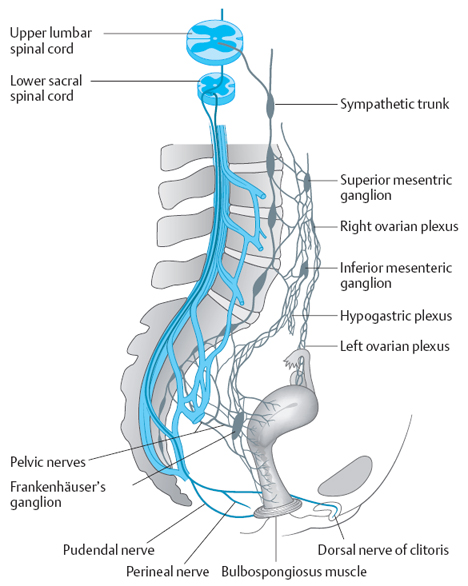

Poor posture can lead to many symptoms, including pain and dysfunction in the pelvic floor. Pelvic floor weakness or pain can also alter sitting or standing posture. There are many conditions affecting both posture and the pelvic floor and leading to pain and dysfunction. All of the body’s systems are involved in maintaining good posture and ensuring healthy, strong pelvic floor muscles. Figure 1.38 illustrates how fragile the nervous system is and the way in which changes of posture, weakness or muscle imbalances, injuries or fractures to the pelvic and abdominal area can have considerable impact on the pelvic floor muscles, nerves, and ligaments.

Possible Posture Conditions Affecting the Pelvic Floor

Possible Posture Conditions Affecting the Pelvic Floor

- Environment and lifestyle

- Altered length tension of muscles in the pelvic, low back and hip area

- Myofascial pain

- Weakness of back extensor and abdominal muscles

Environment and Lifestyle

Environment and Lifestyle

Environment and lifestyle can influence the health of the pelvic floor. In some cultures, for example, the pelvis is important and is emphasized during dance and movement, while in other cultures it is regarded as taboo.

Krüger and Krüger [1991] observed women in Cameroon and reported that incontinence was less common there in comparison with Europe and North America. They attributed this to the integration of pelvic movements into dancing and activities of daily living. Women in Cameroon frequently sit on the floor and lean forward when working—in contrast to women in Europe and North America, where the pelvic muscles usually are held in a horizontal plane, carrying the weight of the viscera most of the time during the activities of everyday life.

Tanzberger [1998] pointed out that in the Islamic religion, both women and men kneel and lean forward during their five daily prayers, unloading the pelvic floor up to 1825 times annually. Individuals who squat or kneel during activities of daily living, as is customary in many countries, activate muscle chains that may contribute to good postural control and promote consistent strengthening of muscles in the legs, pelvic floor, and trunk (Fig. 1.39).

The stability, mobility, and muscle strength in the pelvic region may be lost in the sedentary, “modern” Western lifestyle, where people travel by car and use elevators instead of climbing stairs. Fashions requiring the wearing of tight corsets or girdles, which at times are considered socially desirable, cause a variety of postural, abdominal, and pelvic symptoms, as they maydisplace and compromise the internal organs [Schmidt 1913]. Pitfalls today include “textile contractures,” involving shortened muscles due to the wearing of tight clothes. Many young adults lack mobility in their hip joints (and compensate for this with excessive lumbar flexion) because their tight pants do not allow normal hip movement. Constantly wearing high-heeled shoes can influence the posture unless the hip muscles are kept flexible. Weakness and altered length tension of muscles in the hip, pelvis, and lower back region ensue, as described below. Individuals who spend time sitting on a couch watching TV, who have come to be known as “couch potatoes,” can develop back and pelvic floor problems due to their lifestyle. A lifestyle of this type also compromises diaphragmatic breathing. Unfortunately, the evidence for this is still only clinical, rather than statistical.

Altered Length Tension of Muscles in the Pelvic Area, Lower Back, and Hips

Altered Length Tension of Muscles in the Pelvic Area, Lower Back, and Hips

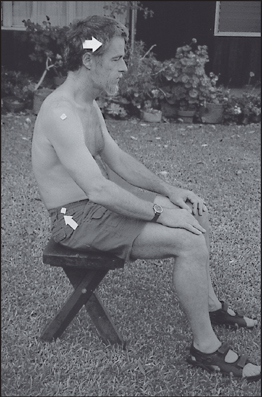

Poor sitting posture is frequently attributed to shortness of the muscles attached to the pelvis, such as the hamstring and tensor fasciae latae muscles. In the sitting position, tight hamstring muscles tend to pull the pelvis into extension, causing flexion of the lumbar spine. This posture strains the lower back and alters the load on the pelvic floor muscles. When shortened, the tensor muscle pulls the leg into abduction and rotates the lower leg externally (Fig. 1.40). When this is combined with the wearing of tight pants (obstructing active hip flexion), dyscoordination and dysfunction of the entire abdominal compartment is preprogrammed. In addition to their back pain, the patients frequently present with breathing and pelvic floor dysfunctions.

Example

Example

A male patient aged approximately 60 attended physical therapy for chronic lower back pain. His sitting posture was as described above. When questioned, he stated that wearing tight jeans led to worsening of the back pain. Active hip flexion was only approximately 90– 100°, and the hamstrings and tensor muscles were tight. The patient was a “chest-breather” and was not engaging the pulmonary diaphragm correctly. The lumbar stabilizers, including the transversus abdominis muscle, were weak. The therapist explained to the patient that it is important to include activation of the pelvic floor muscles when exercising the trunk muscles, in order to improve the foundation of the low back. This could help prevent post-void dribble in the future (see the section on male incontinence, pp. 415–439). The patient then admitted to already having post-void dribble. The treatment included:

- Postural exercises

- Mobilization of the hip joints in all planes

- Breathing exercises

- Stretching of the tight muscles and strengthening of antagonists

- Stabilization of the intrinsic low back muscles and the transversus abdominis muscle

- Pelvic floor strengthening and relaxation exercises (anterior and posterior muscles) also combined with functional activities and breathing

Three weeks into the treatment, the patient reported that he had no more dribbling after voiding. He had also learned to integrate breathing into functional activities and to lean forward by flexing the hips (by moving the pelvis forward and downward) rather than flexing the spine. His back pain was greatly reduced.

Teenagers regard sitting with a rounded back and abducted legs as appropriate and “cool.” Sahrmann [1993, 2002] emphasizes that a fault in a base element (the musculoskeletal system) involves alteration of the length-tension properties of the muscle. In a multisegmented system in which many segments contribute to any motion, the path of least resistance is taken. The more flexible muscles move, while the stiff ones do not. Altered length tension in the muscles can therefore also lead to pathological conditions such as trigger and tender points (see section 2.2 below, pp. 149–164). Wiese [2003] describes the treatment of tender points within the tensor fasciae latae (as well as mobilization of the sacrum) to treat dysmenorrhea. In a study of men with chronic pelvic pain, Hetrick et al. [2003] found that more of them had abnormal pelvic floor musculature findings and increased tension and palpation pain in the psoas muscle in comparison with the control group. Since a shortened pain-sensitive psoas muscle is common in patients with poor posture, therapists should at least ask their patients about pelvic pain.

Shortness of the rectus abdominis muscle increases trunk flexion, causing shortening of the pectoral muscles and forward-pulled shoulders. The neck extensor muscles tighten when the head is tilted backward, as can be observed in conjunction with a flexed spine or forward head (see also section 1.6 below, pp. 98–117). Muscles opposing the shortened or tight muscles tend to be overstretched. Both overstretched and short muscles can be weak and contribute to muscle imbalances [Kendall et al. 1993, Sahrmann 2002].

Poor posture can change the position of the pelvic floor in space and cause stretching or straining of the pelvic floor muscles. Strain can cause decreased muscle strength [Sahrmann 2002]. Pain can be felt if, for example, posture is poor, the tissues are stretched unduly, and nociception signals tissue damage. The result can be abnormal motor output, which then leads to muscle dysfunction [Lee 1996] (see also section 1.6 below, pp. 98–117).

Poole et al. [1997] state that optimal muscle performance depends critically on adequate blood flow and its microvascular distribution. In overstretched muscles, the blood flow and oxygen delivery are compromised, and this increases fatigability. A vicious cycle is initiated: fatigue encourages poor posture, which increases further changes in the length tension of the muscles. The muscles consequently overstretch, weaken, and fatigue even faster.

Prolonged sitting in poor posture contributes to pelvic floor muscle stretching and increased intradiskal pressure. This is important, since many musculoskeletal structures in the back and lower extremities share their segmental innervation with the urogenital structures [Baker 1998]. Altered length tension is discussed in more detail in section 1.3, pp. 35–68.

Myofascial Pain

Myofascial Pain

Travell and Simons [1992] describe trigger points and radiating pain patterns occurring in the muscles surrounding the pelvic floor. Myofascial pain develops when a muscle or its fascia becomes hyperirritable. This occurs whenever a muscle is splinting or guarding against pain. The pain can have neurological, postural, or psychological origin, but can also be due to acute or chronic inflammation, such as cystitis, interstitial cystitis, vulvodynia, coccygodynia, or proctalgia, etc.; resulting spasms and trigger points in the muscles can cause postural changes and dyspareunia [Costello 1998]. In a case study, Doubleday et al. [2003] describe the way in which local mobility restriction in the thoracolumbar region, in a patient who had a central disk protrusion at T12–L1, revealed that active movements in that region provoked buttock and testicular pain.

Myofascial pain is expressed by hypertonus and trigger points in muscles. Altered length tension in the muscles can therefore lead to myofascial pain. Travell and Simons [1992] state that patients with active trigger points tend to move slowly and protectively. Klein-Vogelbach [2000] states that poor posture influences muscles in the following way: muscles that have to support body weights they are not normally required to hold become painful because they lack resting periods and may become ischemic. Other muscles that are not supporting the body weights they normally have to hold become inactive and weak. This may have consequences for the pelvic floor muscles, which can weaken due to inactivity secondary to poor posture. Altered mechanoreceptor activity can change the proprioceptive feedback mechanisms, while pain can also change movement patterns as the body attempts to protect the area. The muscle tone and synchronization of movement patterns are affected [Lee 1994]. Correction of faulty movement patterns is of utmost importance to prevent chronic pain. Changes in the muscle tone can also be observed in patients with pain in the pelvic and low back region. Such problems may reflect impaired central nervous motor programming—an important precondition for chronic pain [Janda 1991]. Self-relaxation therefore can be helpful in treating pelvic floor problems, especially when the pelvic floor is hyperactive (see section 1.7, pp. 117–128).

Weakness of the Back Extensor and Abdominal Muscles

Muscle weakness allows separation of the parts to which the muscles are attached [Kendall et al. 1993]. This can result in stretch weakness, as described by Sahrmann [1993, 2002]. Muscle shortening holds the parts to which the muscles are attached closer together. If the muscle remains in the shortened position, adaptive shortening develops [Kendall et al. 1993]. Myofascial pain and tender points [Wiese 2003] can develop (see also see section 2.2, pp. 149–164). In the standing and upright sitting positions, the back muscles have to have good strength to maintain posture against the force of gravity. Weaknesses in the abdominal and back muscles contribute to poor stability in the lumbar pelvic region. The strength of the deep muscles, such as the multifidus in the back and the transversus abdominis muscle, are crucial to lumbar–pelvic control and stabilization [Hodges and Richardson 1996, Hamilton and Richardson 1997]. The lumbar multifidus, which is continuously active during upright posture and walking, is an example of a muscle that contributes to tonic postural function [Sapsford et al. 2000, Richardson et al. 1999].

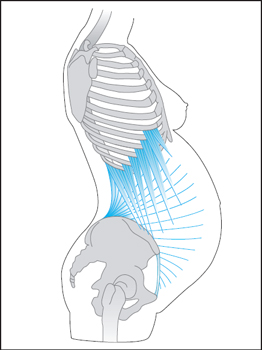

All abdominal muscles, together with the pulmonary diaphragm and the pelvic floor, provide anterior stability to the lumbar spine. Weakness in the rectus abdominis muscles is especially problematic during pregnancy and in the presence of diastasis recti. When separation of the rectus sheath is pulled apart instead of being approximated during exercises, the problem worsens and may cause pubic pain and myofascial pain in the abdominal and pelvic floor muscles [Baker 1998, Costello 1998]. If the oblique abdominal muscles have to take over the function of a weak rectus abdominis, there is a mechanical disadvantage for the spine [Martius 1947] (Fig. 1.41).

Relaxation of the abdominal wall therefore contributes to postural changes, and if it is not corrected it can lead to chronic low back pain. Weakness in the muscles of the abdomen, back, and pelvic floor alters the direction of intraabdominal pressure during coughing, sneezing, or straining (Fig. 1.42). This results in additional strain on a weak pelvic floor [Versprille-Fischer 1997, Richardson et al. 1999, Heller 2001].

In addition, when the length tension of the muscles in the abdomen and back is changed, it prevents the pulmonary diaphragm from moving freely during respiration, thereby hindering its posterior/lateral expansion [Larsen 2001].

During lifting and straining, mild intraabdominal pressure, together with good abdominal and back muscle activity, stabilizes the spine [Lewit 1999, Richardson et al. 1999, Larsen 2001]. Practicing correct lifting during rehabilitation of the pelvic floor is therefore of paramount importance. It may also be necessary to review the way in which exercise equipment is used in a fitness club, and both women and men have to be taught to carry out biomechanically correct lifting, with coordinated contraction of the pelvic floor muscles (Fig. 1.43).

Weakness in the abdominal muscles can be observed when coughing. Heller [2001] suggests testing a person in the standing position: when the hands are placed on the abdomen and the individual coughs, the abdominal wall should contract inward and upward. After childbirth, women with weak abdominal muscles and those with weak pelvic floor muscles cough outward and downward. Weak pelvic floor structures simply do not withstand the increased abdominal pressure.

Possible Conditions in the Pelvic Region Affecting Posture

Possible Conditions in the Pelvic Region Affecting Posture

- Pain from scars in the abdominal or pelvic area

- Pelvic pain or discomfort

- Muscle weakness and shortness

Pain from Scars in the Abdominal or Pelvic Area

Pain from Scars in the Abdominal or Pelvic Area

Example

Example

Pelvic floor or lower abdominal pain can cause poor posture. A patient presented for physical therapy treatment for a shoulder–arm pain syndrome of unknown origin. Because of her poor posture, in a stooped forward position that was causing muscular imbalances in the shoulder– arm region, the patient was asked if she had any scars or pain in the abdominal area. The patient stated that she had had pain for many years in the left lower abdominal quadrant from a cesarean section scar. Both her doctor and her husband had told her that she could not have any pain where there was only a scar. She was denied pain medications and had started stooping to avoid stretching on the abdomen. This habit caused her posture to deteriorate. Successful treatment of the shoulder therefore included mobilization of the scar.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree