The pluralism of injury prevention, as evidenced by its close ties to at least three different cabinet-level agencies in the United States—Health and Human Services, Justice, and Transportation—has made it one of three areas cited by the Institute of Medicine as highly suitable for interdisciplinary study.

2 In this way, the 20th century has been rife with

landmarks in injury prevention. Some of these events are accomplishments at singular points in time although many formed the basis of activities that continue today. The traffic safety movement of the 1920s and the home safety movement of the 1950s are two such examples

3,

4,

5 (see

Table 1).

Given its landmark achievements in injury prevention thinking and study, the 20th century has also witnessed some noteworthy reductions in injury. In fact, motor vehicle safety has been cited as one of the top ten public health achievements in the United States over the last century. This is largely based on reductions in traffic deaths due to safer vehicles and highways, increased use of safety belts, child safety seats, and motorcycle helmets, as well as decreased drinking and driving.

6However, it is worth noting that in the last century mortality reductions from injuries of all causes (not simply motor vehicle crashes) have been far less than those of other diseases, such as influenza, tuberculosis, and gastroenteritis

7 (see

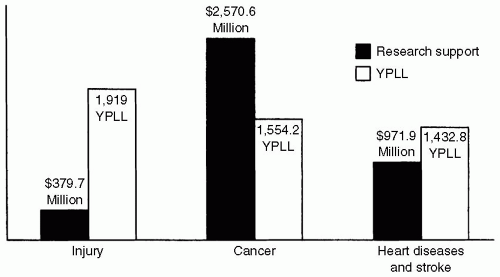

Fig. 1). This relatively low level of success may be related to the fact that the federal research investment in injury prevention has been, and continues to be, very low proportional to the public health burden posed by the disease of injury

8 (see

Fig. 2). Certain mechanisms of injury have been limited or even proscribed in terms of receiving resource support from certain federal agencies. For instance, since 1997 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have not been legally permitted to fund “activities designed to affect the passage of specific Federal, State, or local legislation intended to restrict or control the purchase or use of firearms.”

9 Correspondingly, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest public health research agency in the United States, has only granted one major research award per million firearm injury cases per decade in the last 30 years

10 (see

Table 2). Therefore, federal public health support of firearm injury research has been in short supply relative to the magnitude of the problem.

11