Chapter 11. Injuries to the trunk

Rib fractures

The severity of rib fractures depends on their number and stability. Multiple fractures which interfere with breathing have serious complications, but isolated cracks can usually be treated as severe bruises.

Isolated fractures

Fractures of a single rib can follow a direct blow or, in elderly patients, a fit of violent coughing. At the moment of fracture the patient feels sudden pain in the chest followed by pain on deep inspiration. On examination, there is well localized tenderness at the fracture site and pain on ‘springing’ the ribs.

It is most unwise to reassure patients that their ribs are intact just because the radiographs do not show a fracture. Radiographs only show the fracture if the X-ray beam catches it at exactly the right angle, which is rare, and for practical purposes clinical signs are more reliable than radiographs in the first week after injury.

After 2 weeks, the fracture can be recognized more easily by the rarefaction of the bone ends and callus around the fracture.

Treatment

Isolated fractures seldom require active treatment and can be regarded as ‘a bad bruise’. Untreated, they are very painful for 10–14 days and moderately painful for a further 4 weeks. By 8 weeks from injury they should be pain-free, when the callus can be felt as a firm bony swelling at the fracture site.

Analgesics are essential in the first few days and an intercostal block with local anaesthetic is sometimes needed. Breathing is painful without analgesia, chest movement is limited, the underlying lung develops atelectasia, secondary infection can follow and the patients may die if they are infirm.

Strapping the chest. Once the standard treatment for all fractured ribs (Fig. 11.1), strapping relieves pain by restricting rib movement. Today, strapping is indicated only for robust, hard-working individuals who wish to get on with their job and pretend that the injury never happened.

|

| Fig. 11.1 Strapping for broken ribs. |

In dire emergencies, such as the battlefield, a pad bandaged over a flail segment reduces its excursion and minimizes the interference with inspiratory volume. A pad and bandage is also helpful if there is a penetrating wound of the pleura because it closes the opening into the pleural space.

Although valuable as an emergency measure, strapping is not good long-term treatment. Restricting thoracic movement and relying on diaphragmatic movement alone for breathing leads to lobar collapse, which predisposes to chest infection and creates further respiratory difficulties. Definitive treatment is therefore determined by the type of fracture and the stability of the chest.

Multiple fractures

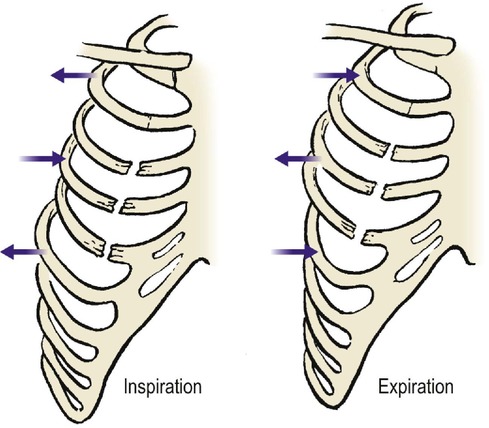

Flail chest. The main function of the ribs is to act as a moving cage to suck air into the lungs as it is elevated by the chest musculature. If this rigidity is lost and part of the chest wall is free to move independently of the rest of the thorax, it will be sucked inwards when the patient attempts to inhale and blown outwards on exhalation (Fig. 11.2). This is ‘paradoxical respiration’; it dramatically reduces tidal volume and can cause respiratory failure.

|

| Fig. 11.2 A flail chest with paradoxical respiration. An unsupported segment of chest with ribs broken at each end moves inwards during inspiration and outwards during expiration. |

Flail segments are commonly caused by a direct blow to the chest rather than by a crushing injury. A blow from a horse’s hoof produces a circular flail segment about 15 cm across, and a blow to the sternum from a steering wheel can fracture all ribs on both sides to produce a flail segment that includes the mediastinum.

Crushed chest. If a chest is crushed, there will be fractured ribs on both sides of the chest. Because it is difficult to fracture more than three ribs on one side of the chest and leave the other side intact, the presence of more than three fractures on one side of a crushed chest usually means that there are fractures on the other side as well, whatever the radiographs show.

A crushed chest does not usually have paradoxical movement but pain from the fractures interferes seriously with breathing and this can also cause respiratory failure.

Treatment

Treatment of multiple rib fractures depends upon their stability.

Stable fractures. Provided the rib cage is stable and there is no flail segment, inspiration is possible. Treatment is then similar to that of an isolated fracture, but more energetic. The pain is more severe, areas of tenderness are more numerous, inhibition of inspiration is more marked and breathing and movement are more painful. Stronger analgesics or intercostal nerve blocks may be required to make breathing comfortable.

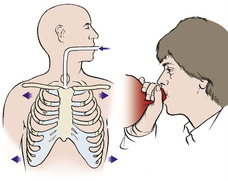

Unstable fractures. Unstable flail segments are best treated by positive pressure ventilation so that the ‘bellows’ function of the chest is disregarded and the chest inflated like a paper bag (Fig. 11.3). Strapping the flail segment is useful until the patient reaches hospital. Positive pressure ventilation can be instituted and, if necessary, maintained by tracheostomy for 2 or 3 weeks until the chest wall is stable.

|

| Fig. 11.3 Positive pressure respiration. If there are multiple rib fractures, the chest may be inflated passively like a paper bag. |

The decision to ventilate a patient is made in conjunction with the thoracic surgeons and anaesthetists and the patient is best managed in the intensive therapy unit.

Pathological fractures

The ribs are a common site for metastatic deposits and pathological fractures are common. Suspected rib fractures deserve radiological examination, even though they are often undetectable.

Injuries to the costal cartilages

The costal cartilages are softer and more flexible than ribs but can be fractured by direct violence. The clinical features are similar to those of an isolated rib fracture but the pain is less severe.

The joints between the costal cartilages of the false ribs can also be injured and dislocations of these joints produce pain and tenderness which can be very slow to resolve.

Treatment

Injection with hydrocortisone acetate is sometimes helpful.

Fractures in the elderly

In the elderly, the pain from rib fractures impairs respiratory function. Pain relief in these patients is particularly important and local infiltration of the fracture with local anaesthetic or an intercostal nerve block may be required.

Injuries involving the pleural cavity

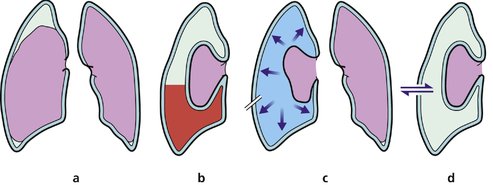

There are three types of pneumothorax (Fig. 11.4):

1. Closed

2. Open

3. Tension.

|

| Fig. 11.4 Types of pneumothorax: (a) simple pneumothorax; (b) haemopneumothorax; (c) tension pneumothorax; (d) open pneumothorax. |

If lung and pleura are damaged, a pneumothorax, haemothorax or chylothorax may follow.

Closed pneumothorax

Most pneumothoraces consist of nothing more than a little air in the pleural cavity which will be absorbed in a few days (Fig. 11.5). Because the air in the pleural space floats upwards, a pneumothorax cannot be seen on an anteroposterior radiograph unless the patient is standing or sitting upright, when it is seen above the clavicle.

|

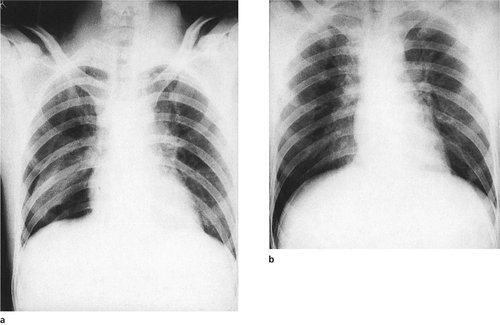

| Fig. 11.5 Simple pneumothorax: (a) marked collapse and (b) very slight collapse of the right lower lobe. |

If the pneumothorax is small, the only evidence may be the absence of lung markings at the apex. If a standing or sitting radiograph is not possible, a lateral radiograph may show air lying against the lateral wall of the chest.

Treatment

A pneumothorax occupying more than 25% of the hemithorax causes respiratory embarrassment and draining may be needed, using a catheter attached to an underwater seal.

Open pneumothorax

If the skin and parietal pleura are broken, the pleural space will communicate with the outside air, which will be sucked in and out of the chest on inspiration and expiration. Respiratory embarrassment follows unless the opening is closed. Infection is an additional risk but is unusual if the lung can be kept expanded and the pleural space obliterated.

Treatment

As first aid, a pad can be placed over the opening, or the patient simply laid with the wound downwards until a chest drain can be inserted. It is not necessary to close the wound unless it is large or contaminated.

Tension pneumothorax

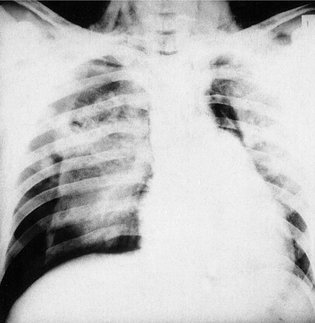

If the opening into the pleura is oblique it can work like a flap valve and allow air into the pleural cavity on inspiration but will not let it out on expiration (Fig. 11.6). The pleural space will then be inflated under pressure, the lung will collapse and the mediastinum will shift to the opposite side. Unless treated promptly, the patient will die within minutes. This is a tension pneumothorax.

|

| Fig. 11.6 Bilateral pneumothorax with tension pneumothorax on the right side. Note the surgical emphysema in the neck. |

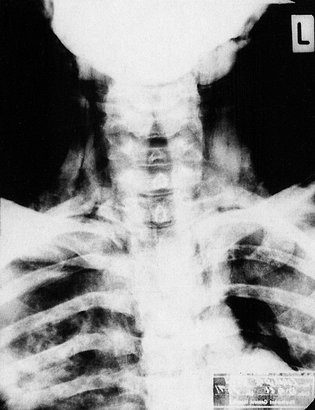

If there is a rib fracture as well, the air will be forced out through the fracture site into the subcutaneous tissues to produce surgical emphysema, which can extend over the whole of the chest wall and into the neck (Fig. 11.7). A similar appearance is also seen after vigorous positive pressure ventilation of patients with fractured ribs.

|

| Fig. 11.7 Massive surgical emphysema caused by rupture of a main bronchus. |

Treatment

In patients with a tension pneumothorax the insertion of a chest drain is a life-saving procedure. A pneumothorax or chest drain pack is available in all accident departments and every doctor likely to be exposed to such a patient should know how to use it.

Emergency treatment of tension pneumothorax

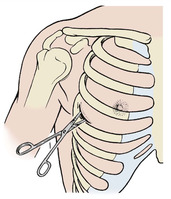

1. Make a short skin incision in the fourth rib space (i.e. between the fourth and fifth ribs) in the midaxillary line on the side of the pneumothorax (Fig. 11.8).

|

| Fig. 11.8 Site of drainage of a tension pneumothorax at the fourth intercostal space in the midaxillary line. Keep the scissors close to the upper border of the lower rib. |

2. Dissect right down through the intercostal muscles and pleura with scissors. Open the scissors widely to release air. The hiss of air will be felt and heard and the patient will improve dramatically.

3. Pass a chest drain through the incision and into the pleural cavity. The situation is then under control.

4. Secure the drain to the patient and connect it to an underwater seal or valve.

To push a pair of sharp scissors into a patient’s chest may seem hazardous, but in a patient with a tension pneumothorax the vital structures are pushed well away from the point of entry. There is no time for a radiograph to confirm which side of the chest is involved but this is obvious clinically because the affected side contains so much air that it is tympanitic to percussion.

Haemothorax

Bleeding into the pleural cavity will produce a more gradual deterioration than a pneumothorax. The pulse rate rises, blood pressure falls and the chest is dull to percussion; the diagnosis can be confirmed radiologically.

Treatment

Treatment is by drainage as described, or if the bleeding cannot be controlled then a thoracotomy may be required to stop the bleed.

Chylothorax

Damage to the thoracic duct can cause chyle (lymph) to run into the pleural cavity, producing a chylothorax, which causes a steady deterioration.

Treatment

Treatment is difficult and may require the attention of the thoracic surgeons to close a thoracic duct leak, but many heal spontaneously with tube drainage and parenteral nutrition. Healing may take several weeks and the patient must take nothing by mouth during this time.

Injuries to the mediastinum

The steering column of every car is aimed liked a spear at the heart of the driver and injuries to the mediastinum are a common cause of death. Despite collapsible steering columns, steering wheels contoured to fit the thorax (Fig. 11.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree