Chapter 6 Injuries to the Tibialis Anterior, Peroneal Tendons, and Long Flexors of the Toes

Flexor hallucis longus

Tendinitis

Acute tendinitis occurs most commonly at the posterior ankle.1 This injury is common in dancers and has been termed “dancer’s tendinitis.”2–4 It is less common than Achilles tendinitis and occurs in inexperienced dancers and in athletes who are not conditioned. Tendinitis also develops when athletes change sports without proper conditioning for the new activity. Symptoms begin within a few days following a change of technique or at the beginning of the season. When the dancer rises on the ball of the foot, pain occurs in the posterior aspect of the ankle. The pain initially is vague and occurs with flexion of the ankle and foot. Passive dorsiflexion of the ankle with deep palpation 1 cm anterior and medial to the Achilles tendon at the ankle joint elicits tenderness and crepitus.2

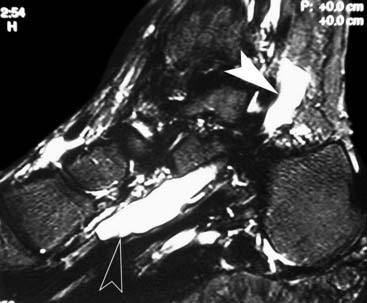

Chronic tendinitis produces symptoms of tenderness in the same region with active flexion and also on deep palpation of the tendon during flexion and extension.5 Crepitus is present over the tendon. Radiographs differentiate this from os trigonum syndrome and arthritis of the subtalar joint. Symptoms of os trigonum syndrome include pain in the posterior ankle when the patient actively rises on the ball of the foot. The provocative test is reproduction of pain with passive forced plantarflexion of the foot and ankle. The differential diagnosis includes pseudocyst of the flexor hallucis longus tendon, symptomatic subtalar cyst, posterior impingement syndrome, and insertional Achilles tendinitis. MRI helps to rule out a mass but may show a “dumbbell”-shaped configuration of fluid in the tendon sheath around the ankle, narrowing beneath the sustentaculum and enlarged distal to the sustentaculum tali (Fig. 6-1).

In the well-conditioned athlete, the muscles of the calf are hypertrophied. Because of the low insertion of the fibers of the flexor hallucis longus muscle onto its tendon, dorsiflexion of the ankle draws the enlarged lower muscle fibers into the fibro-osseous tunnel through which the tendon passes behind the ankle. This causes inflammation at the musculotendinous junction, the stopper bottle sign, and symptoms of posterior ankle pain. Treatment includes anti-inflammatory medication and a flexibility program including gentle stretching.6 If symptoms do not abate, surgical intervention with release of the pulley and tenosynovectomy may be necessary. In cases in which significant hypertrophy of the muscle is present, a myoplasty, excision of impinging muscle fibers, may be necessary. The tendon is debrided, and fibrosed muscle fibers that attach on the tendon just above the pulley also are excised to permit smooth passage of the tendon in the tunnel throughout its full excursion.

Other areas of chronic tenosynovitis of the tendon include the midfoot and metatarsophalangeal joint.7 Symptoms of pain with tenderness usually occur in the specific area of stenosis. To relieve symptoms, the pulleys in either of these areas are released surgically, and a tenosynovectomy is performed. Injections of corticosteroids should be avoided because inadvertent injection directly into the tendon may cause it to rupture.2

Trigger toe

Partial rupture of the flexor hallucis longus tendon consists of a longitudinal tear in the tendon and a fusiform thickening at the distal end of the tendon tear beneath the sustentaculum tali.4,8,9

Occasionally the tendon may be trapped in a fracture.10–12 When the nodule on the tendon lies distal to the sustentaculum, the narrow tunnel through which the tendon passes restricts motion in a manner similar to that of the flexor pulley of trigger finger. The result is triggering of the great toe. The condition occurs commonly in ballet dancers and is more common in females in their second to fourth decades. As the dancer begins to rise (relevé) on the ball of the foot (demi-pointe), the great toe dorsiflexes and remains in contact with the floor (Fig. 6-2: photos of toe flexed and extended). The flexor hallucis longus contracts, but the tendon excursion is limited by the nodule’s position at the distal end of the tarsal canal. Once the dancer has achieved demi-pointe, pain may occur in the posterior ankle. As the dancer further rises onto her toes (sur les pointes), the great toe plantarflexes from 90 degrees dorsiflexion to neutral position to support the body. The pull of the flexor hallucis longus muscle is strong enough to force the nodule proximally through the stenotic tunnel, triggering the great toe into flexion. While the dancer is en pointe, the nodule lies proximal to the tunnel. As the dancer returns from pointe to flat foot, the tendon is passively pulled distal, and the fuseform thickening in the tendon snaps forward distally through the stenotic tunnel again. As the great toe snaps straight, it produces pain and may alter the dancer’s appearance in the dance step. The longitudinal tendon tear usually is single, but it may be multiple, and measures from 3 to 5 cm in length.

Radiographs exclude bony abnormalities. MRI reveals a tear with degeneration of the tendon. A pseudocyst of the tendon may be present.13 The differential diagnosis includes a posterior impingement syndrome of the ankle, os trigonum syndrome, retrocalcaneal bursitis, and Achilles tendinitis. Conservative therapy consisting of gentle stretching exercises, and anti-inflammatory medication to reduce swelling may be effective. Patients with compromised performance who fail to respond to conservative measures are surgical candidates.

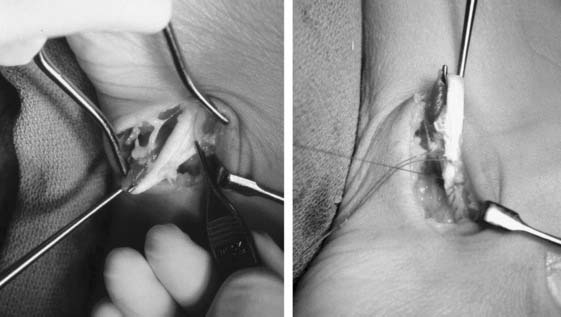

Surgical approach consists of a 5-cm incision on the posteromedial aspect of the ankle. The posterior tibial neurovascular structures are retracted medially. The tendon is delivered through the wound with a tendon hook, and the pulley is released at its lateral attachment to the talus and calcaneus distally. The nodular swelling present at the distal end of the tear is trimmed to conform to the uniform diameter of the tendon throughout its length (Fig. 6-3). The tear is repaired with a running 4-0 braided nonabsorbable suture. The tendon must be trimmed to slide easily in the canal throughout full flexion and extension. Following closure, a splint is applied until two weeks postoperatively. A gentle active range of motion (ROM) program is begun 3 weeks following surgery. The foot and ankle are protected for 3 additional weeks in a splint, and the patient then is transitioned to an ankle stirrup brace. Dancing en pointe may take up to 4 months, whereas return to full athletic routine usually occurs by 3 months. Full recovery may take 6 months.

Case Study 1

A 28-year-old, female, classical ballet dancer noticed increasing pain in her posterior ankle following dance class for 2 months. She then developed a snapping of her great toe when rising from the demi-pointe position (on the ball of the foot) to en pointe position (on her toes). A triggering sensation was felt behind the ankle. When descending from en pointe position to a flat foot, the great toe snapped again as the toe dorsiflexed. Pain was felt behind the ankle. The snapping of the foot was visible and became unaesthetic as well as disabling. Physical examination revealed a palpable popping sensation felt posteriorly at the ankle as the foot, ankle, and great toe were moved repeatedly from dorsiflexion to plantarflexion. At surgery, a 5-cm incision was made at the posteromedial aspect of the ankle, and the flexor hallucis longus muscle and tendon were identified. Traction with a tendon hook revealed a 5-cm longitudinal tear in the tendon beginning at the musculotendinous junction and extending distally (see Fig. 6-3, A and B). The fibro-osseous canal through which the tendon passed was noted to be tight. A fusiform thickening of the tendon was present at the distal end of the tear. The thickened tendon was trimmed sharply so that the width of the tendon was uniform throughout, and the tendon sheath was carefully released, allowing the tendon to slide its length unimpeded through a full ROM of the ankle and foot. The tear was repaired with 4-0 braided Ethibond suture. A splint was applied for 3 weeks, followed by gentle active ROM and a supervised physical therapy program. Three months later, the dancer was able to resume dance. She returned to dancing sur les pointes 4 months after surgery. Six months following surgery, she was asymptomatic.

Complete rupture

Complete rupture of the flexor hallucis longus is uncommon but can occur in several areas. Iatrogenic surgical laceration has been described.14 Avulsion fracture from the hallux distal phalanx is caused by great resistance to flexion on the distal phalanx as the foot is forcibly plantarflexed. If the avulsed tendon contains a fragment of bone, anatomic open reduction is recommended. Tear of the tendon at its insertion without a bony fragment permits the tendon to retract proximally, allowing the great toe to dorsiflex. Surgical repair is performed through a medial incision along the proximal phalanx of the hallux above the neurocirculatory bundle. The tendon sheath is exposed at or just proximal to the metatarsophalangeal joint with a direct repair of the tendon to the distal phalanx.

Tendon rupture also can result following corticosteroid injection into the tendon at the metatarsophalangeal joint (Fig. 6-4). Symptoms include pain, sudden loss of active flexion at the interphalangeal joint, and weakness in flexion at the metatarsophalangeal joint. This is accompanied by a dramatic change in athletic performance. Chronic, complete, spontaneous rupture also has been reported in basketball players and aerobic walkers at the sustentaculum tali. Symptoms occur over a 6-week period.

Treatment in the high-performance athlete consists of surgical repair. If the tendon has retracted proximally and cannot be reapproximated, a tendon graft using plantaris tendon may be necessary to reestablish continuity. Reconstruction returns strength to flexion of the metatarsophalangeal joint, although a flexion lag at the interphalangeal joint commonly results.2,4

Complete rupture of the flexor hallucis longus tendon within the tarsal tunnel and beneath the sustentaculum tali may be treated by transfer of the flexor digitorum longus to the stump of the flexor hallucis longus.15,16 Resection of the degenerated portion of the flexor hallucis longus tendon also is performed. The flexor digitorum longus tendon lies adjacent to the flexor hallucis longus beneath the sustentaculum tali. Suturing of the flexor hallucis longus tendon stump to the flexor digitorum longus tendon proximal to the master knot of Henry permits good function, if not complete return of strength.

An alternative method of treatment for complete rupture is to use a tendon graft. The graft is sutured proximally and distally following resection of the diseased portion of the flexor hallucis longus tendon. The foot and ankle are immobilized for 6 weeks.17 Both methods provide good function of the flexor hallucis longus but do not necessarily return normal flexion to the hallux interphalangeal joint. In some patients with low demands on the foot, complaints of a hyperextended distal phalanx rubbing on top of the shoe persist. Arthrodesis of the hallux interphalangeal joint in 20 degrees of flexion provides relief of symptoms without altering performance.

Tumor masses

The most common mass of the flexor hallucis longus tendon is a pseudocyst located at the posterior ankle. It may extend distally into the foot along the tendon sheath and is associated with degeneration or tears of the tendon. Symptoms of fullness and achiness along with decreased performance are common. Symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome also have been reported. An MRI reveals a cystic mass, often bilobed, with one end at the posterior ankle and the other end distal to the tarsal tunnel in the midfoot (Fig. 6-1). If symptoms warrant, excision of the cyst and tenosynovectomy are performed through a posteromedial ankle incision. Associated tendon tears are repaired as described previously. Postoperatively, the ankle is protected in a splint for 3 weeks, followed by initiation of a flexibility and power-building program. Return to play is permitted when postoperative pain subsides and foot function approaches the level of the normal, contralateral side.

Tibialis Anterior

Anatomy

The tibialis anterior muscle lies in the anterior compartment of the leg and originates from the proximal lateral tibial metaphysis and proximal two thirds of the tibial shaft and interosseous membrane. The tendon twists and crosses the extensor hallucis longus tendon at the level of the ankle at which it enters a synovial tendon sheath. The tendon courses dorsomedially across the foot and rotates 90 degrees from the myotendinous junction to the broad insertion.18 The majority of tendons insert at the plantar medial border of the first metatarsal and medial cuneiform. Approximately 10% of tendons have variations to the insertion, the most common being a bifid insertion to the cuneiform and first metatarsal, or insertions reaching proximally or distally along the medial column of the foot.19,20 Accessory tibialis anterior tendons have been reported, but are rare and have not been reported to cause pathology.

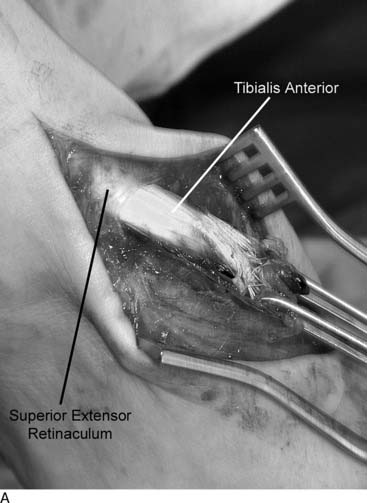

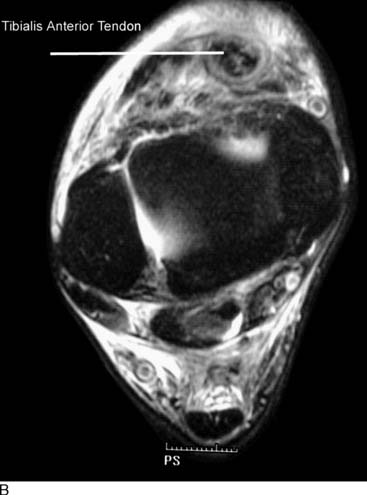

The tibialis anterior is bounded proximally to the ankle by the superior extensor retinaculum, and variably may enter a synovial tendon sheath within the retinacular fibers at this level. More distally, the tibialis anterior tendon predictably enters a synovial sheath as it passes into the inferior extensor retinaculum complex. An early study using a modified Spaltehoz technique failed to reveal any zones of hypovascularity within the tendon,21 but a later study using immunohistochemical methods suggests that such a zone exists within the inferior retinacular system where tendon rupture is most likely to occur.22,23

Tibialis anterior tendinitis

The diagnosis is readily appreciated on physical examination. Physical findings include pain with palpation of the tendon and pain with resisted dorsiflexion. The tendon may be tender, particularly as it passes under the superior extensor retinaculum. Palpable synovitis, swelling, and crepitance are variably present. In cases in which weakness in dorsiflexion is present, or when swelling and tenderness exist more distally within the inferior extensor retinaculum or at the tendon insertion, a more aggressive workup is required to rule out intrasubstance degeneration or impending rupture. In these instances, MRI or ultrasound are useful tools for evaluating tendon continuity and tendonosis24–26 (Fig. 6-5).

In younger, athletic individuals, the area of inflammation usually involves the superior extensor retinaculum and responds well to conservative management. A three-phase rehabilitation protocol is used to resolve the tendinitis.6,27 Phase I involves limiting the extent of injury and diminishing inflammation. An oral anti-inflammatory is initiated, and the area may be iced and wrapped with an ACE bandage to diminish pain and swelling. Immobilization is rarely indicated, but discontinuation of the exacerbating activity is required for 10 to 14 days. Phase II is started after pain and swelling have diminished and involves guided rehabilitation. Equinus contracture must be addressed with frequent stretching exercises. Resistive exercises with elastic tubing can isolate the tibialis anterior for pliability and strengthening. Therapeutic modalities also can be helpful because of the subcutaneous positioning of the tendon. Phase III involves return to activity. Running should be initiated on a flat surface such as a track or treadmill, with gradual advance of mileage and hilly terrain as tolerated. We avoid the use of steroid injections around the tendon sheath because of the risk of rupture.28,29 Rarely, proximal degeneration of the tendon occurs that does not resolve with appropriate rehabilitation techniques. In these recalcitrant cases, surgical exploration and tenosynovectomy may be required to resolve symptoms. Pain and swelling of the tendon at or near its insertion represents a different disease process and may represent significant degeneration and impending rupture, as discussed in the next section.

Tibialis anterior rupture and laceration

The tibialis anterior tendon is vulnerable to laceration because of its subcutaneous position over the anterior aspect of the foot and ankle.30 The tendon may be cut in a “boot top” laceration when a sharp object such as a skate, ski edge, or sharp cleat cuts the skin and underlying structures.31,32 Dropping a sharp object onto the dorsum of the foot also can result in laceration. A high index of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis because these lacerations typically look benign, with minimal bleeding or pain. Dorsiflexion of the ankle will be weakened and lack full extension but will be intact because of the secondary action of the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL). Routine exploration of all dorsal foot and ankle lacerations should be performed if there is suspicion of partial or complete tendon laceration. These structures heal well and have minimal dysfunction when repaired acutely. Traumatic rupture may occur because of higher energy blunt trauma and is associated with anterior compartment syndrome.33–38

Spontaneous rupture of the tendon at or near its insertion is the more common presentation of tibialis anterior deficiency. It typically occurs in middle-aged athletes and often accompanies other comorbid conditions, such as diabetes, inflammatory arthritis, gout, obesity, and steroid use.24,39–42 The tendon in this location may demonstrate a zone of relative hypovascularity near its insertion that may predispose it to tendinosis and rupture in this area. A prodrome of pain and swelling along the medial arch variably precedes rupture. Pain and tenderness at the insertion of the tibialis anterior tendon should be treated as an impending rupture. The patient is immobilized in an ROM boot unlocked in dorsiflexion but locked at 0 degrees of plantarflexion. This allows active tendon remodeling and motion while protecting the tendon from further degeneration. Physical therapy is initiated with the goals of decreasing inflammation and encouraging tendon remodeling through therapeutic exercises and modalities. The ROM boot is unlocked gradually to allow more plantarflexion as symptoms permit. The boot may be discontinued after 4 to 6 weeks. In recalcitrant cases or elderly individuals, a hinged ankle foot orthosis (AFO) with a plantarflexion stop may be necessary to control symptoms and prevent tendon rupture.

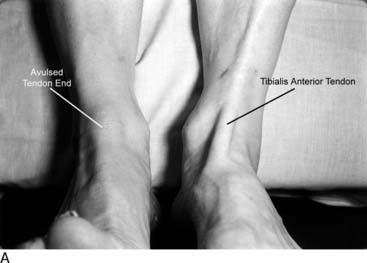

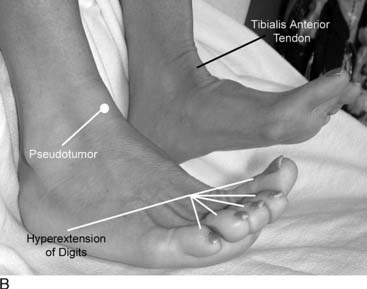

Rupture of the tibialis anterior in the middle-aged athlete often is the result of a minor trauma. The mechanism of injury involves a strong contraction of the muscle with the ankle in plantarflexion. The rupture may be painless, but dysfunction is noted immediately by the patient, who develops a slapping gait and experiences tripping on his or her toes. Medical attention may not be sought for weeks, and the diagnosis often is missed at the initial evaluation.5,43 The diagnosis can mimic peroneal nerve or L5 nerve root dysfunction.40,44,45 Diagnosis may be made by physical examination and presents as the classic triad of ankle dorsiflexion by hyperextension of the toes, a slapping gait, and a mass over the anterior ankle (pseudotumor) (Fig. 6-6). Weakness in ankle dorsiflexion occurs because the tibialis anterior function is lost, but ankle dorsiflexion is still present because of the secondary function of the digital extensors. The patient complains of a slapping gait and has notable difficulty clearing his or her toes during swing phase. The mass over the anterior ankle, or pseudotumor, is the avulsed tibialis anterior tendon stump, which becomes entrapped at the inferior border of the superior extensor retinaculum.

Repair may be performed early or late, but the results of surgery are better if repair is performed within the first 3 to 6 weeks. Nonoperative treatment is acceptable for elderly, inactive patients, but primary or delayed repair is preferred for active individuals regardless of age.46–49

Surgical treatment of tibialis anterior tendon rupture

In rupture of the tibialis anterior tendon, the ruptured tendon end often becomes caught at one of the extensor retinacular layers and easily may be palpated beneath the skin. The skin incision is made in line with the axis of the tendon from 1 to 2 cm proximal to the palpable tendon end and carried distally to the terminal insertion at the plantar medial aspect of the first tarsometatarsal joint (Fig. 6-7). Deeper dissection involves incision of the inferior extensor retinacular sheath for the tibialis anterior tendon, which usually is well defined. If the delay to surgery has been greater than 3 or 4 weeks, the tendon sheath will have filled with fibrous tissue, which must be excised sharply or removed with a small rongeur. In more acute cases, the sheath may be filled with fluid or hematoma. Atraumatic tendon rupture usually occurs by partial avulsion from the insertion and elongation of the degenerative tendon within the inferior extensor retinaculum. Twenty percent to 30% of the distal tendon stump may remain in continuity with the anatomic insertion and, if present, should be preserved for use in the repair. In exposing the proximal tendon stump, consideration should be given to the superior extensor retinaculum. When possible, the superior extensor retinaculum should be left intact during exposure of the tendon. The retinaculum at the level of the ankle often is thin, and repair can be difficult. Adhesions of the repaired tendon to the retinaculum are common and difficult to avoid because of the immobilization required in the postoperative protocol. In patients with comorbid conditions, the retinaculum may not be repairable, possibly leading to subcutaneous adhesions, bowstringing of the tendon, and wound healing problems. Often retraction of the tendon will stop at the inferior margin of the superior extensor retinaculum, either because the tendon end has formed a pseudotumor that becomes entrapped here or because some of the more proximally inserting fibers are still in continuity.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Pearl

Pearl

Pearl

Pearl

Pearl

Pearl

Pearl

Pearl