The optimal management and care of both blunt and penetrating neck trauma has undergone significant evolution in the last few decades. However, optimal management of some injuries remains unclear and is the subject of active investigation. Many of the changes have been spurred by the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic technologies that have increased the safety and efficacy of nonsurgical management.

Historically the management of neck trauma has been influenced by military experience with high-energy missile and blast injuries. This generated protocols that mandated surgical neck exploration, which lowered the rate of missed injuries but increased the number of nontherapeutic surgeries. However, in this age of “cost-containment” and evidence-based medicine, the economic cost, resource utilization, and high morbidity of exploratory neck surgery has led to some authors and trauma centers questioning this management protocol in civilian practice.

As with all other anatomic locations, blunt and penetrating injuries often require different management approaches. Considering the plethora of vital structures that reside in this compact anatomic region, neck injuries can result in significant morbidity and mortality. Seemingly innocuous wounds may not manifest clear signs or symptoms, and potentially lethal injuries could be easily overlooked or discounted. Therefore the surgeon faced with initially managing a traumatically injured person must be cognizant of the currently recommended guidelines for the evaluation and the management of neck injuries.

In this overview, we review, in a systems fashion, the diagnosis and management of the various blunt and penetrating injuries encountered by the surgeons managing these patients. This chapter provides practical guidelines and algorithms for the safe evaluation and management of civilian patients, with soft tissue injuries of the neck. Cervical spinal cord injuries and cervical spine fractures will not be addressed in this chapter.

EPIDEMIOLOGIC FEATURES

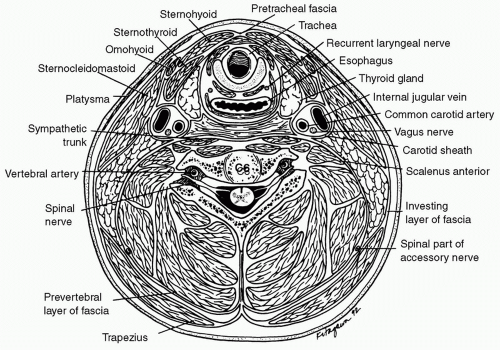

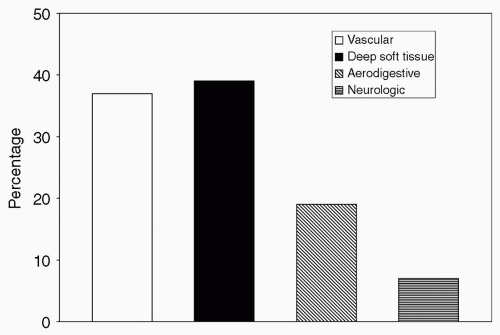

Most neck trauma is due to a penetrating mechanism. As shown in

Fig. 1, most of the penetrating neck trauma in the United States occurs as a result of interpersonal violence with firearms being the most common weapon of choice. These injuries most often affect the vascular system or results in injury of the great vessels or lung apices (see

Fig. 2). Blunt neck trauma stems from a variety of etiologies. Motor vehicle crashes, falls, hangings, and chiropractic neck manipulations have all been documented to lead to blunt injuries.

Penetrating neck trauma represents approximately 5% to 10% of all trauma cases that present to the emergency department. Approximately 30% of these cases are

accompanied by injury outside of the neck zones as well. The current mortality rate in civilians with penetrating neck injuries ranges from 3% to 6%. Whereas blunt neck trauma is fairly common, actual soft tissue injuries from blunt trauma is relatively rare and has been estimated to be < 1% of all neck injuries.

1 Despite its relative rarity, blunt laryngotracheal (LT) trauma carries a mortality rate that can be as high as 40%, whereas the mortality rate of penetrating LT injuries is approximately 20%.

2

ANATOMIC FEATURES

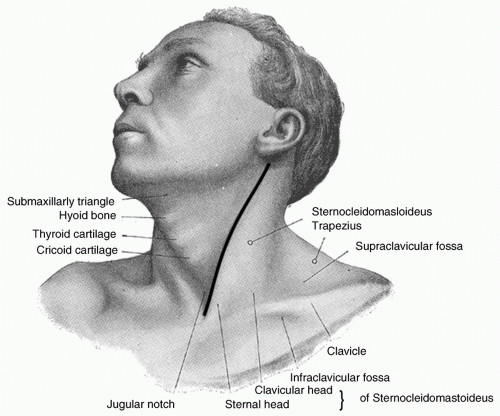

Successful management of neck injuries depends on a clear understanding of the anatomy of the neck. The close proximity of vital structures with the anterior third of the neck is clearly demonstrated in the cross-sectional view of the neck as shown in

Fig. 3.

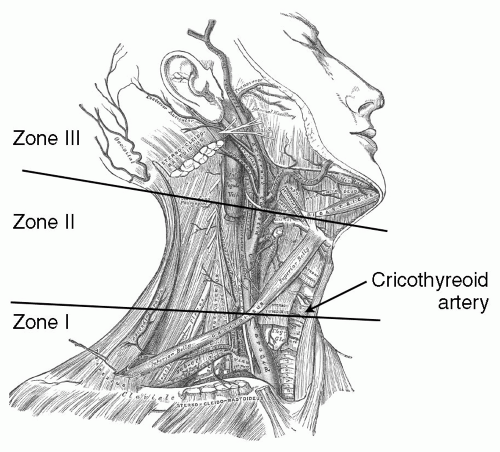

For the purposes aiding clinical decisions for diagnostic testing and management, surgeons have described the neck by dividing it into three anatomic zones in the caudal to cranial orientation as shown in

Fig. 4. The six organ systems within these neck zones include vascular, respiratory, digestive, neurologic, endocrine, and skeletal. The vascular system includes the innominate, subclavian, axillary, carotid, jugular, and vertebral vessels. The respiratory system includes the larynx, trachea, and the lung. The

digestive system includes the pharynx and esophagus. The neurologic system includes the spinal cord, brachial plexus, cranial nerves, and the sympathetic chain. The endocrine system includes the thyroid and parathyroid. The skeletal system includes the cervical spine, clavicle, upper rib cage, and skull base.

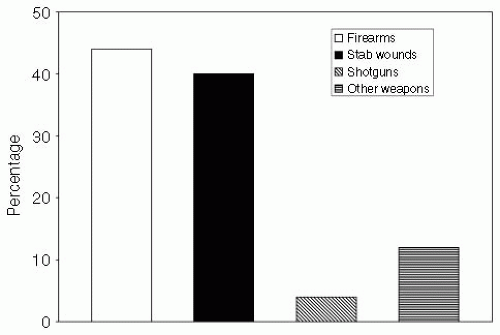

Serving as the line of demarcation, the sternocleidomastoid muscle separates the neck into anterior and posterior triangles. Most of the important vascular and visceral organs lie within the anterior triangle bounded by the sternocleidomastoid posteriorly, the midline anteriorly, and the mandible superiorly. Except for individual nerves to specific muscles, few vital structures cross the posterior triangle, which is delineated by the sternocleidomastoid, the trapezius, and the clavicle (with the exception of the region just superior to the clavicle). The area of injury depends on the mechanism of injury. Overall, zone II is the most commonly injured area (see

Fig. 5).

4Zone I, the base of the neck, is demarcated by the thoracic inlet inferiorly and the cricoid cartilage superiorly. Vascular structures at greatest risk in this zone include the innominate vessels, jugular veins, common carotid artery origin, subclavian vessels, and vertebral artery. Other important nonvascular structures located within this zone include the brachial plexus, trachea, esophagus, apices of the lungs, thoracic duct, cervical spine, and cervical nerve roots. Surgical exposure of these structures, particularly the vascular structures, is difficult because of the presence of the clavicle. Furthermore, signs of a significant injury in the zone I region may be hidden from inspection by residing within the chest or the mediastinum.

Zone II encompasses the midportion of the neck and is defined as the region between the cricoid cartilage and the angle of the mandible. Important structures in this region include the carotid and vertebral arteries, jugular veins, pharynx, larynx, trachea, esophagus, and cervical spine and spinal cord. Zone II, in comparison with zones I and III, is the most easily accessible region for clinical examination and surgical exploration. Therefore, zone II injuries are likely to be the most apparent on physical examination and are also the easiest to evaluate intraoperatively without the aid of preoperative diagnostic testing.

Zone III defines the superior aspect of the neck and is bounded by the angle of the mandible and the base of the skull. Diverse structures, such as the salivary and parotid glands, cervical spine, the distal extracranial carotid arteries, jugular veins, and major nerves (including cranial nerves IX-XII), traverse this zone. Zone III is not amendable to easy physical examination or surgical exploration; therefore, injuries in zone III can require special diagnostic studies to aid in management.

PREHOSPITAL MANAGEMENT

The evaluation of a patient with penetrating neck trauma should always begin with Advanced Trauma Life Support, a paradigm that starts with a directed primary survey emphasizing airway, breathing, and circulation. However, attempts to manage the airway and resuscitate the patient in the field are ill advised and potentially dangerous. Therefore, the scene time should be kept to a minimum,

especially if there is a short transport time to the nearest designated trauma center.

Bleeding control can be achieved by direct pressure and the risk of an air embolism can be reduced by the placement of patient in the Trendelenburg position. Placement of intravenous (IV) lines can be attempted en route to the hospital. Oxygen can be administered by mask or nasal cannula. However, assisted ventilation with bag-valve-mask may be contraindicated because it may result in massive subcutaneous emphysema or air embolus in patients with an open LT injury. Furthermore, prehospital endotracheal intubation should be attempted only in patients in extremis, have a compromised airway, or have anticipated prolonged transport times. Most low-velocity gunshots and stab wounds do not result in airway compromise, but high-velocity gunshot and shotgun wounds and severe blunt trauma will often necessitate emergent airway management.

Traumatized airways are usually challenging to intubate because of the primary injury, blood, tissue, local edema, and debris. Blind intubation can result in the endotracheal tube creating a false passage or complete the transection of an injured trachea resulting in severe morbidity. Blind intubation should not be attempted because of its inherent low success rate and the high mortality of a failed blind intubation. It is important to remember that a surgical airway is sometimes needed and prehospital personnel must be prepared for this scenario before any attempts at endotracheal tube placement.

Cervical spine protection by means of a neck collar remains a common practice during the prehospital transportation. Given the high incidence of cervical spine fracture associated with high-energy penetrating neck injuries, cervical immobilization should be attempted when feasible.

5 However, it should be abandoned if it would cause an undue delay or hindrance to emergent management of the patient and may, in fact, be harmful in patients with an expanding hematoma that may cause respiratory obstruction.

Zone I injuries can have a concomitant pneumothorax, which can be simply treated during transport by placing a large-bore needle and IV catheter into the pleural space. Additionally, if a large venous injury is suspected, peripheral IV line placement should be on the contralateral side to the injury to minimize fluid extravasation and to maximize the ability to replete the patient’s intravascular volume.

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT/TRAUMA BAY MANAGEMENT

Airway Management

Upon arrival at the emergency department, the patient should be surveyed and treated for immediate life-threatening conditions as delineated in the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols.

6 Airway management is the first and most challenging priority in the management of severe penetrating neck injury. In a review by Vassiliu et al., 29% of patients with LT trauma and 41% of patients with pharyngoesophageal (PE) trauma required emergency intubation.

7Airway compromise may arise due to direct trauma or severe edema to the larynx or trachea or from external compression by a stable or expanding hematoma. Management of airway in patients with penetrating neck injury should be individualized according to the condition of the patient, the nature of the injury, and the experience of the trauma team.

Ideally, there is an experienced anesthesiologist on the trauma team to assist with advanced airway management. A surgeon should always be present in case an emergent surgical airway is warranted because up to one fourth of patients with aerodigestive tract trauma have failed rapid sequence induction intubation.

7 If a surgical airway is required and there is an obvious LT wound, the endotracheal tube can be carefully inserted under direct vision into the distal airway. Creation of surgical airway in these challenging conditions requires a closely coordinated team effort between the surgeons and the anesthesiologists.

In most emergent situations a cricothyrotomy is the surgical airway of choice rather than a tracheostomy. The more inferior placement of a tracheostomy has a lower rate of tracheal stenosis than with cricothyrotomies. However, the exposure required for a tracheostomy is often more technically challenging due to the location of the anterior jugular veins and the thyroid gland and its associated vasculature. A cricothyrotomy safely avoids the thyroid gland and most of the anterior vessels of the neck. The higher rate of late complications associated with cricothyrotomy can be avoided by electively converting it to a tracheostomy 1 to 2 days after the patient’s condition allows for the procedure.

Circulation Management

As in the prehospital setting, the patient should be placed in the Trendelenburg position when there is active bleeding to reduce the risk of air embolism from venous injuries. Hemorrhage control can often be achieved simply by direct pressure in most patients. However, in the event that external pressure is not effective, as in the case of bleeding from the vertebral or subclavian vessels, digital compression with a gloved index finger inserted into the wound may be more effective in temporizing the bleeding en route to the operating room.

Regardless of the zonal location of injury, exsanguinating hemorrhage, expanding hematoma, refractory shock, airway compromise, and severe subcutaneous emphysema (see

Table 1) are all indications for immediate surgical exploration and intervention.

8 Finally, for those patients in cardiac arrest or imminent cardiac arrest, an anterior

resuscitative thoracotomy may be indicated if an injury to zone I vasculature is suspected.

9 The thoracotomy exposure should allow for intrathoracic direct control of zone I vascular injuries. However, the survival rate following resuscitative thoracotomy for penetrating neck injury is very poor.