Inflammatory Myopathies: Polymyositis, Dermatomyositis, and Related Conditions

Irene Z. Whitt

Frederick W. Miller

|

A previously healthy 54-year-old librarian comes to the clinic complaining of “tired and sore arms and legs” for the previous 7 weeks. This came on gradually after a cruise to the Caribbean, while playing golf in the sun all day, but she has continued to get weaker, to the point that she needs help getting in and out of her bathtub and has difficulty reaching high shelves at work. Despite avoiding the sun since the cruise ended, she has a faint, persistent “sunburn” on her hands and knees. She is fatigued and has difficulty with breathing while going upstairs. She has noticed more heartburn than usual, and sometimes solid food “comes back up.” She denies taking any illicit drugs, has had no medication changes recently, and drinks wine only occasionally. Looking at her chart, you note that she has had a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone and electrolyte panel in the past 1 year, but she did not get the mammogram, Papanicolaou smear, or colonoscopy you had recommended.

Clinical Presentation

Inflammatory myopathies are diseases characterized by acquired muscle inflammation. This term encompasses a large number of disorders that include viral, fungal, and parasitic infections of muscle, toxic myopathies, and other causes of muscle damage. When the appropriate clinical, laboratory, and pathologic studies eliminate known causes of muscle inflammation, a diagnosis of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) can be made (1). Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy is very rare, with an incidence of approximately 9 to 12 cases/million/year. It typically manifests either in young children or in adults in the fifth decade of life, though it can present at any age. Women are more affected than men (2).

The three most common forms of IIM are polymyositis (PM) and inclusion body myositis (IBM), where inflammation is found in multiple muscles, and dermatomyositis (DM), in which inflammatory changes occur in the skin as well as muscles. In PM and DM, inflammation is also frequently systemic, and occurs in other organs such as the joints, lungs, heart, or gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This inflammation manifests as direct organ infiltration by mononuclear cells, frequent immune abnormalities, and the production of autoantibodies. This, in addition to a

demonstrated response to therapies that decrease inflammation, has led to the classification of IIM as autoimmune diseases. Yet, the IIM themselves are a heterogeneous group of rare syndromes that differ considerably in their clinical presentations, pathologic findings, disease courses, and prognoses (3).

demonstrated response to therapies that decrease inflammation, has led to the classification of IIM as autoimmune diseases. Yet, the IIM themselves are a heterogeneous group of rare syndromes that differ considerably in their clinical presentations, pathologic findings, disease courses, and prognoses (3).

Clinical Points

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathy is a diagnosis of exclusion, and the differential diagnosis can be challenging.

Symmetric proximal muscle weakness predominates; a good functional assessment of the patient is required in order to distinguish true weakness from pain that limits function.

Rashes in DM can be subtle, and most are not pathognomonic.

Patients may have clinical weakness before or in the absence of elevated muscle enzymes; a muscle biopsy is required in most cases for definitive diagnosis, especially in patients without the pathognomonic rash of DM.

Cancer has been associated with IIM, especially DM; age-appropriate cancer screening should be performed. Women with IIM should be evaluated for ovarian cancer.

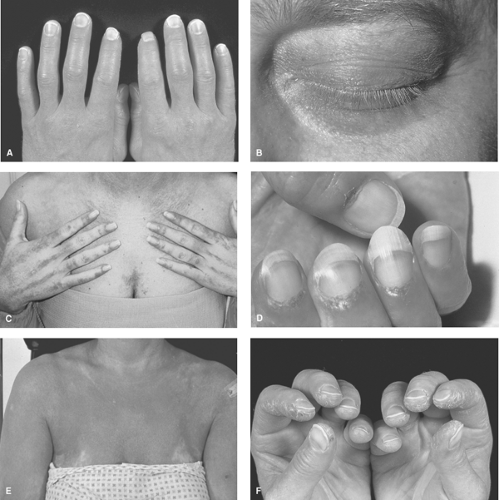

Most patients with DM present with characteristic rashes over the knuckles (Gottron’s papules; see Fig. 13.1A) or around the eyes (heliotrope rash; Fig. 13.1B) and progressive, symmetric proximal muscle weakness, more pronounced in the legs than the arms, evolving over weeks to months. Patients with PM present with the weakness, but not the rash. They usually have hip muscle weakness, and notice increasing difficulty getting up from a chair or climbing stairs. The shoulder muscles often become symptomatic later, resulting in difficulty combing the hair or reaching objects on high shelves. Importantly, only one quarter of patients with DM or PM have significant muscle pain or tenderness. In the absence of objective weakness, hip or shoulder girdle pain as the only presenting complaint suggests an alternative diagnosis, such as polymyalgia rheumatica.

Other skeletal muscles can be affected, and 20% of patients have dysphagia (with nasal regurgitation of liquids signifying greater severity), while a smaller subset experiences respiratory insufficiency from respiratory muscle weakness. Subtle signs of extramuscular inflammation may also be present if carefully sought. Patients may have profound fatigue, persistent unexplained low-grade fevers, symmetric small-joint arthralgias or arthritis, abdominal pain, dyspnea on exertion from interstitial lung disease, or palpitations (from cardiac conduction abnormalities) and heart failure related to direct inflammation of the cardiac muscle.

Differential Diagnosis

The IIM are systemic connective tissue diseases, and many other organ systems can be involved, resulting in a wide range of possible presentations and symptoms that can mimic many other disorders. Thus, the differential diagnosis of IIM includes the many disorders associated with muscle complaints and is considerably challenging, not only because of the plethora of conditions to be considered, but also because IIM are so rare that few clinicians are thoroughly familiar with these diseases. One begins with clearly defining the patient’s primary problems. Since patients may use “weakness” and “pain” interchangeably, questions should focus on (1) distinguishing myalgias from true weakness, which is often painless, by focusing on the patients’ functional abilities (what they can and cannot do in their daily routine) (2); the location of weakness (proximal muscles in PM and DM vs. distal muscles in IBM and other disorders; symmetric weakness in PM and DM vs. asymmetric muscle involvement in IBM and other disorders) (3); the time frame and tempo of symptom progression and whether atrophy is present, signifying a chronic course most consistent with dystrophies (4); and any associated nonmuscular symptoms such as fatigue, low-grade fevers, rashes, breathing or swallowing difficulties, arthritis or arthralgias, which suggest a systemic disease, such as IIM.

A Differential Diagnosis of Muscle Weakness or Pain

Noninflammatory Myopathies

Endocrine (hypo- and hyperthyroidism, acromegaly, diabetes, Cushing’s syndrome, Addison’s disease, hypo- and hyperparathyroidism, hypocalcemia, hypokalemia)

Toxic (ethanol, corticosteroids, cocaine, statins, fibrates)

Metabolic (acid maltase deficiency, carnitine deficiency, uremia)

Congenital

Mitochondrial

Muscular Dystrophies

Myotonia

Neuropathies [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Guillain–Barre syndrome, diabetic plexopathy]

Neuromuscular junction disorders (Eaton–Lambert syndrome and myasthenia gravis)

Overuse syndromes

Paraneoplastic (carcinomatous neuropathy, cachexia, myonecrosis)

Rhabdomyolysis

Tendonitis–fasciitis

Inflammatory Myopathies

Infectious

Bacterial (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Clostridia, Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

Viral (influenza, adenovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, coxsackievirus, hepatitis B and C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1))

Fungal (Candida, coccidiomycosis)

Parasitic (trichinosis, toxocariasis, cysticercosis, trypanosomiasis, toxoplasmosis)

Toxic (L-tryptophan, eosinophilia myalgia syndrome)

Graft-versus-host disease

Rheumatic conditions (giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosum, overlap syndromes with lupus and scleroderma)

Macrophagic or eosinophilic myofascitis

Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies (see Table 13.1)

Next, one needs to consider possible causes. Has the individual been exposed to any myotoxins, licit or illicit drugs, botanical or other over-the-counter preparations that could result in myopathy, or a metabolic abnormality such as hypokalemia? Has the patient had any recent unusual exposure, infection, or travel? Are there any symptoms or findings that suggest thyroid or parathyroid disease, diabetes, or an underlying malignancy? Is there a family history of a similar disorder that would suggest a dystrophy or inherited myopathy?

Diagnostic Criteria

Criteria to define the IIM syndromes and distinguish them from other myopathies were proposed more than 30 years ago (4) and remain useful today. Since these are diagnoses of exclusion, one must first do an evaluation directed by the history and physical examination findings to exclude the many other causes of myopathy. Once this has been accomplished, a diagnosis of IIM can be made using the findings of acute or subacute symmetric proximal muscle weakness, significant elevation of muscle enzymes, characteristic EMG abnormalities, and muscle biopsy findings or rashes consistent with IIM (Table 13.1). In unclear cases, additional clues that can assist in making the diagnosis of IIM include the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) or myositis autoantibodies (5), a family history of autoimmune disease, detection of inflammatory changes in muscles by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (6), or a clinical response to immunosuppressive therapy (Table 13.2).

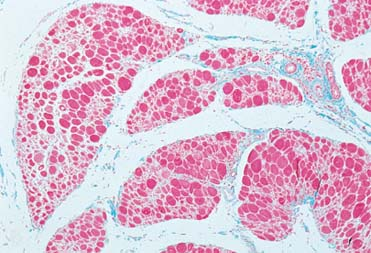

Inclusion body myositis is the most common IIM occurring in patients older than 50 years. Patients with IBM usually fulfill the IIM criteria, but in contrast, have more slowly progressive weakness of the quadriceps and distal muscles of the arms, in a somewhat asymmetric fashion; lower elevations of serum CK levels; and characteristic amyloid deposits and rimmed vacuoles within myocytes seen on light microscopy. Some inflammatory changes may be present, but amyloid deposition predominates. Although some patients may initially improve with immunosuppressive treatments, most have a gradual and relentless progression of muscle weakness.

Table 13.1 Bohan and Peter Criteria for the Diagnosis of Dermatomyositis (DM) and Polymyositis (PM)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 13.2 Useful Discriminators for Myositis in Confusing Cases of Myopathy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cancer-associated myositis is another IIM disorder, and on the basis of population studies (7), can be considered if both diagnoses are made within 2 years of one another. Treating the underlying cancer generally also treats the myositis. Although molecular genetic studies have identified genes responsible for many dystrophies, metabolic, and mitochondrial myopathies, some patients continue to defy diagnostic evaluations and remain enigmas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree