Chapter 181 Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis)

Diagnostic Summary

Diagnostic Summary

• Abdominal pain the most common symptom—can be localized anywhere in the abdomen

• Complicated by intestinal obstruction, abscesses, fistulas, strictures, perianal disease

• Intermittent bouts of diarrhea or constipation, low-grade fever, and weight loss

• Frequently misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome; time to diagnosis from onset is estimated to be approximately 8 years

• Serologies, ileocolonoscopy, and capsule endoscopy are key diagnostic modalities

• Radiographic evidence of abnormality of the terminal ileum is characteristic

• Stools are high in lactoferrin and calprotectin—noninvasive inflammatory markers

• Genetic predisposition, environmental trigger (infection, medications, etc.), chronic full-thickness patchy intestinal inflammation

• Risk of digestive tract cancer higher than in the general population

• Bloody diarrhea with cramps in the lower abdomen

• Mild abdominal tenderness, weight loss, fever

• Involves only the colon; distinguishing point from Crohn’s disease, which can involve any portion of the alimentary tract

• Inflammation is superficial and continuous

• Diagnosis is confirmed by radiography and sigmoidoscopy

• Risk of colon cancer increased after 10 years of disease and universal distribution throughout colon

• Genetic predisposition, triggers similar to those of Crohn’s disease

General Considerations

General Considerations

Definition

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is characterized by a granulomatous inflammatory reaction comprising the entire thickness of the bowel wall. In approximately 50% of cases, however, the granulomas are either poorly developed or totally absent. The original description in 1932 by Crohn and colleagues localized the disease to segments of the ileum. However, the same granulomatous process may involve the buccal mucosa, esophagus, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and colon. Rectal biopsies are routinely recommended during flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy because granulomas are most commonly found at this site. Crohn’s disease of the small intestine is also known as regional enteritis. Involvement of the colon is known as Crohn’s disease of the colon or granulomatous colitis; the latter designation is less accurate because granulomatous lesions develop in only some of these patients.

Common Features of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

• The colon is frequently involved in Crohn’s disease and is invariably involved in ulcerative colitis.

• Although rarely, patients with ulcerative colitis who have total colon involvement may experience a so-called backwash ileitis. Thus, both conditions may cause changes in the distal small intestine.

• Patients with Crohn’s disease often have close relatives with ulcerative colitis, and vice versa.

• When there is no granulomatous reaction in Crohn’s disease of the colon, the two lesions may resemble each other clinically as well as pathologically.

• There are many epidemiologic similarities between the two diseases, including age, race, gender, and geographic distribution.

• The two conditions are associated with similar extraintestinal manifestations.

• There appear to be etiologic parallels between the two conditions.

• Both conditions are associated with a higher frequency of colonic carcinoma.

Etiology

The epidemiologic and etiologic data on ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are quite similar.1,2 The incidence and prevalence of the two diseases differ slightly, with most studies showing UC to be more common. The current estimate of the incidence of UC in western Europe and the United States is approximately 6 to 8 cases per 100,000; the estimated prevalence is approximately 70 to 150 cases per 100,000. The estimate for the incidence of CD is 2 cases per 100,000, and that for the prevalence is 20 to 40 cases per 100,000. The incidence of CD is rising in Western cultures.3,4

IBD may occur at any age, but it most often occurs between the ages of 15 and 35 years. Females are affected slightly more frequently than males. White people have the disease two to five times more often than African or Asian Americans, and Jews have a threefold to sixfold higher incidence than non-Jews.1–4

Theories about the etiology of IBD can be divided into several groups, as follows1,2:

• An assortment of miscellaneous concepts implicating psychosomatic, vascular, traumatic, and other mechanisms

Genetic Predisposition

Although the search for a specific genetic marker for IBD has been futile, several factors suggest a genetic predisposition. As already mentioned, IBD is two to five times more common among white than nonwhite people and four times more common among Jews than non-Jews. In addition, multiple members of the same family have CD or UC in 15% to 40% of cases.1,2

Infectious Etiology

Many microorganisms have been hailed as putative causes of IBD; however, in spite of numerous attempts to confirm a bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, or viral etiology, the idea that a transmissible agent is responsible for IBD is still a hotly debated subject. Viruses—rotavirus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, measles virus, and an uncharacterized RNA intestinal cytopathic virus—and mycobacteria continue to be favored candidates. Gastrointestinal infections with Aeromonas bacteria (Aeromonas sobria and Aeromonas hydrophila) and the yeast Candida albicans can trigger a flare of disease, and all patients with IBD should be tested for these infections at the start and during the course of their illness.5–10 Other etiologic candidates are as follows1,2,11–13:

Antibiotic Exposure

Antibiotic exposure is being linked to CD.1 Before the 1950s, CD was found in select groups with a strong genetic component. Since that time there has been a rapid climb in developed countries, particularly the United States, and in countries that previously had virtually no reported cases. In fact, CD has spread like an epidemic since 1950. Are antibiotics to blame? Penicillin and tetracycline have been available in oral form since 1953. The annual increase in prescriptions of antibiotics parallels the rise in the annual incidence of CD. Comparative statistics have shown that wherever antibiotics have been used early and in large quantities, the incidence of CD is now quite high.

Immune Mechanisms

An overwhelming amount of evidence points to immunologic derangements in IBD, but whether they are causal or secondary phenomena remains unclear. Theories relating humoral mechanisms, immunologic regulatory defects, and cell-mediated reactions to the etiology of IBD have all been proposed, but the current evidence seems to indicate that these derangements are probably secondary to the disease process.1,2

Dietary Factors

Despite the fact that a dietary etiology of CD is barely considered (if mentioned at all) in most standard medical and gastroenterology texts, several lines of evidence strongly support dietary factors as being the most important etiologically.14–26

The incidence of CD is increasing in cultures consuming the Western diet, but it is virtually nonexistent in cultures consuming a more primitive diet.14–19 Food is the major factor in determining the intestinal environment, so the considerable change in dietary habits over the last century could explain the rising incidence of IBD. Several studies that have analyzed the preillness diets of patients with CD have found they habitually eat more refined sugar, chemically modified fats and fast food, and less raw fruits, vegetables, omega-3−rich foods, and dietary fiber than healthy people.14–18 In one study, the preillness intake of refined sugar in patients with CD was nearly twice that in controls (122 g/day vs 65 g/day).18 One researcher found that before the onset of disease, patients with CD had eaten corn flakes more frequently than controls.21 Although other researchers could not verify this specific finding, corn flakes are high in refined carbohydrates and are derived from a very common allergen (corn). Much of controversy over the role of preillness diet in the etiology of CD is largely due to the fact that the only way to assess this diet is from postdiagnostic interviews. Studies in which the interview has taken place within the first 6 months of diagnosis tend to be more supportive than studies in which the interview was conducted more than 7 months after diagnosis. Increased refined sugar intake and high overall carbohydrate intake precede the development of CD.27 Along these lines, patients with UC show a higher consumption of refined carbohydrate than control subjects.28 Increased consumption of chemically modified fats (such as those found in margarine) may be involved in the etiology of UC.29 Interestingly, high consumption of a fast-food diet is an antecedent of both UC and CD.30

Another important dietary factor that is entirely overlooked in the standard texts is the role of food allergy. Support for this hypothesis is offered in clinical studies that have used an elemental diet, total parenteral nutrition, or an exclusion diet with great success in the treatment of IBD.20–25 The role of food allergy is discussed in greater detail later in the chapter, as is the effect of dietary fiber in the etiology and treatment of IBD (see “Therapeutic Considerations”).

A reduced intake of omega-3 oils and an increased intake of omega-6 oils are also being linked with the growing rise of CD in Japan. Because the genetic background of the Japanese is relatively homogeneous, this higher incidence is most likely due to the incorporation of Western foods in the diet. To examine the contribution of diet to the increased incidence of CD in Japan, the incidence and daily intake of a number of dietary components were compared annually between 1966 and 1985. The analysis showed that the greater incidence of CD was strongly correlated with increased dietary intake of total fat, animal fat, omega-6 fatty acids, animal protein, milk protein, and the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids. It was less correlated with intake of total protein, was not correlated with fish protein, and was inversely correlated with vegetable protein. Multivariate analysis showed that higher intake of animal protein was the strongest independent factor, followed by an increased ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids.26 Correction of this increased ratio by reduction of omega-6 oil intake and increase of omega-3 oil intake may lead to significant clinical benefit through an effect on eicosanoid metabolism (discussed later).

Miscellaneous Factors

Psychosomatic factors, primary vascular disease within mural arteries or arterioles, and chronic trauma have received consideration in the etiology of IBD but at present are not considered significant pathogenic mechanisms.1,2 Mental and emotional stress can promote exacerbation of IBD, so stress management techniques may prove useful for some patients.31

Therapeutic Considerations

Therapeutic Considerations

Control of Causative Factors

Natural History of Crohn’s Disease

Little is known about the natural course of CD, because virtually all patients with the disease undergo standard medical care (drugs and/or surgery) or alternative therapy. The only exceptions are patients in clinical trials who are assigned to the placebo group.32–34 However, even these patients do not represent the natural course of the disease, because they are seen frequently by physicians and other members of a health care team and are taking medication, even if it is only in the form of a placebo. If proper evaluation of therapies for IBD is to occur, there must be a greater understanding of its natural history. This is particularly important for alternative practitioners, because it is commonly believed that standard medical care often interferes with the normal efforts of the body to restore health. Some aspects of the “natural” course of CD support this idea, especially when coupled with the limited efficacy of current medications and surgery and their known toxicity. However, heroic measures do have their place in many instances and should be used when appropriate.

Researchers in the National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study (NCCDS) reviewed 77 patients who received placebo therapy in part 1 of the 17-week study.32,33 They all had active disease, as defined by a CD activity index (CDAI) (see Appendix 3) higher than 150. Of the patients completing the study:

• Only 7 (9%) suffered a major worsening of their disease (i.e., either a major fistula developed or the patient required abdominal surgery).

• 25 (32%) suffered a lesser worsening (increase in the CDAI to >450 or presence of fever of 100°F for 2 weeks).

• Treatment was considered to have failed in 25 (32%) because their CDAIs remained higher than 150.

The European Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study (ECCDS), although different in some methodologic details, is quite similar to the NCCDS.32,34 In the ECCDS, 110 patients constituted the placebo group, 68 patients with prior treatment and 42 patients with no prior treatment. The results of the study showed that 55% of the total placebo group achieved remission by 100 days, 34% remained in remission at 300 days, and 21% remained in remission at 700 days. Like the NCCDS, the ECCDS demonstrated that patients with no prior therapy have a greater likelihood of remission.

Although one group of researchers did not advocate placebo therapy, they did carefully point out that once remission was achieved, 75% of the patients continued in remission at the end of 1 year and up to 63% at 2 years regardless of the maintenance therapy used. These results would suggest that the key is achieving remission, which, once attained, can be maintained by conservative nondrug therapy rather than the “medicines we are currently using with their limited efficacy and known toxicity.”32

Eicosanoid Metabolism in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

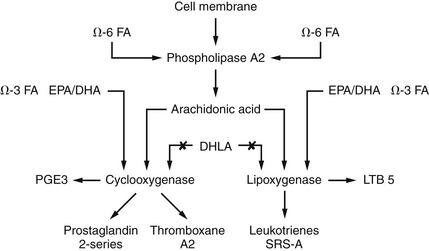

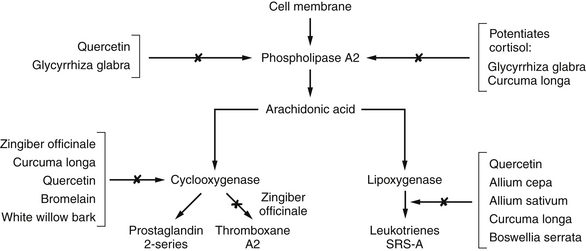

Patients with IBD show greatly increased levels of inflammatory chemicals in the colonic mucosa, serum, and stool samples. Specifically, these patients show an increase in the synthesis of the lipoxygenase products, leukotrienes, and mono-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (mono-HETEs).35–39 These compounds are produced by neutrophils and are known to amplify the inflammatory process and cause smooth muscle contraction. Release of lipoxygenase products is promoted by activation of the alternative complement pathway. The therapeutic efficacy of sulfasalazine and corticosteroids is due to their effect on eicosanoid metabolism (Figure 181-1). Sulfasalazine is an inhibitor of both cyclooxygenase and neutrophil lipoxygenase, whereas corticosteroids inhibit phospholipase A2 and thus block the release of arachidonic acid from the membrane phospholipid pool. Sulfasalazine also inhibits the degranulation of mast cells. Several naturally occurring compounds, such as the polyphenols (quercetin, curcumin, resveratrol, etc.), also interact favorably with these enzymes (Figure 181-2).

Meta-analyses of double-blind studies with fish oil supplements (2.7 to 5.1 g total omega-3 oils) have demonstrated an ability to prevent or delay relapses in both CD and UC.40,41 The Cochrane Collaboration recently published a systematic review evaluating 214 publications and identified only 15 randomized controlled trials. Only 4 studies were of sufficient quality to be included in the analysis. Enteric-coated omega-3 EFA supplementation reduced the 1-year relapse rate by half, with an absolute risk reduction of 31% and a number needed to treat (NNT) of only 3. A much larger RCT asked whether omega-3 fatty acids could sustain remission once it was achieved. Two randomized double-blind placebo-controlled studies (Epanova Program in Crohn’s Study 1 [EPIC-1] and EPIC-2) were conducted between January 2003 and February 2007 at 98 centers in Canada, Europe, Israel, and the United States. Data from 363 and 375 patients with quiescent CD were evaluated in EPIC-1 and EPIC-2, respectively. Patients with a CDAI score of less than 150 were randomly assigned to receive either 4 g/day of omega-3 free fatty acids or placebo for up to 58 weeks. No other treatments for CD were permitted. Clinical relapse is defined by a CDAI score of 150 points or greater and an increase of more than 70 points from the baseline value, or initiation of treatment for active CD. In both EPIC-1 and EPIC-2, there were no significant differences in the CD relapse rate for placebo versus fish oils.42 Flaxseed oil is also of value. Flaxseed oil contains alpha-linolenic acid, an essential omega-3 fatty acid that has antiinflammatory effects and can be converted to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in limited amounts.43

Mucin Defects in Ulcerative Colitis

Mucins are an ill-defined class of high-molecular-weight carbohydrate-rich (85% by weight of N-acetylgalactosamine, galactose, sialic acids, N-acetylglucosamine, and fructose) glycoproteins thought to be largely responsible for the viscous and elastic characteristics of secreted mucus. Alterations in mucin composition and content in the colonic mucosa have been reported in patients with UC.43–46 The factors responsible for these changes appear to be a dramatic drop in the mucous content of the goblet cells (proportional to the severity of the disease) and a diminution of the major sulfomucin subfraction (designated “species IV,” according to diethylaminoethanol-cellulose differentiation). In contrast, these abnormalities are not found in patients with CD. It is significant that, although the mucin content of the goblet cells returns to normal during remission, the sulfomucin deficiency does not. The specific components of the sulfomucin and the cause of its lower concentration have not yet been determined. These mucin abnormalities are also thought to be a major factor in these patients’ higher risk of colon cancer.

Intestinal Microflora

The intestinal microflora is extraordinarily complex and contains more than 400 distinct microbial species.11,12 Accurate simultaneous quantification of all possible species is not possible with current conventional culture techniques. In addition, measurement techniques such as stool cultures do not indicate bacterial metabolic activity, locations of growth within the gastrointestinal tract, or turnover rates. These last two factors may prove to be the more important determinants of the role of the intestinal bacterial flora in IBD than the actual numbers of specific bacterial species. In an effort to describe a nonspecific (qualitative or quantitative) alteration in the intestinal flora, the term dysbiosis is often used (see Chapters 10 and 27 for a full discussion of this important topic).11

The fecal flora of patients with IBD has been found to contain higher numbers of gram-positive anaerobic coccoid rods and Bacteroides vulgatus, a gram-negative rod.11 Studies have indicated that these alterations in fecal flora are not secondary to the disease, and alterations in the metabolic activity of the various bacteria are thought to be more important than alterations in the number of bacteria per se. In addition, specific bacterial cell components (which vary even within the same species) are thought to be responsible for promoting lymphocyte cytotoxic activity against the colonic epithelial cells.11,12

Carrageenan

Interestingly, researchers investigating the intestinal flora of UC often use the carrageenan (a sulfated polymer of galactose and D-anhydrogalactose extracted from red seaweeds, principally Eucheuma spinosum and Chondrus crispus) model to induce the disease in animals experimentally. In the initial experiments reported by Marcus and Watt47 in 1969, 1% and 5% carrageenan solutions were provided as the exclusive source of oral fluids for guinea pigs. Over a period of several days, the animals lost weight, demonstrated anemia, and had bloody diarrhea. Gross anatomic studies after sacrifice at 20 and 45 days revealed a loss of haustral folds, mucosal granularity, pseudopolyps, and strictures; microscopic examination showed crypt abscesses, lymphocytic infiltration, capillary congestion of the lamina propria, and gross ulcerations. These results have since been confirmed by numerous investigators and in studies involving other animal species, including primates.5,48–50

As suggestive as the animal studies are in linking UC with carrageenan and despite the higher consumption of carrageenan in Western diets, at this time there appears to be no correlation between the human consumption of carrageenan and the development of UC. In one study, no lesions of IBD were observed in healthy human subjects fed enormous quantities of degraded carrageenan.51 However, differences in intestinal bacterial flora are probably responsible for this discrepancy, because germ-free animals do not display carrageenan-induced damage.

On further examination, it was discovered that the bacterium linked to the carrageenan-induced damage in animals is a strain of B. vulgatus.11 As mentioned earlier, this organism is found in much higher concentrations (six times as high) in the fecal cultures of patients with IBD. When all the data are evaluated, they appear to imply that although carrageenan can be metabolized into nondamaging components in most human subjects, those individuals with an overgrowth of B. vulgatus may be at risk. Strict avoidance of carrageenan appears warranted at this time for patients with IBD until further research clarifies its safety for them.

Aspirin and Intestinal Permeability

A very interesting study evaluated 30 patients with CD and 37 first-degree relatives of patients with CD for intestinal permeability by means of the lactulose/mannitol ratio. First-degree relatives had a 110% higher intestinal permeability after ingesting acetylsalicylic acid, compared with an increase of 57% in the control subjects. Thirty-five percent were “hyperresponders.”52 A familial permeability defect causing increased permeability would be a significant predisposing factor for CD, because a leaky gut is associated with higher incidence of food allergy and greater absorption of intestinal toxins (see Chapter 20).

Endotoxemia and the Alternative Complement Pathway

Endotoxemia is associated with both CD and UC.52,53 Endotoxemia-induced activation of the alternative complement pathway could explain some of the extraintestinal (i.e., outside the gastrointestinal tract) manifestations of IBD (discussed later). Whole-gut irrigation significantly reduces the endotoxin pool in the gut and has been shown to have a very beneficial antiendotoxemia effect.54 Colonic irrigation may offer similar benefit. However, colonic irrigation during an acute inflammatory flare may be contraindicated.

Extraintestinal Manifestations

More than 100 disorders, known as extraintestinal lesions (EILs), constitute a diverse group of systemic complications of IBD.2,55,56 The most common EIL in adults is arthritis, which is found in about 25% of patients. Two types are typically described, the more common being peripheral arthritis affecting the knees, ankles, and wrists. Arthritis is more common in patients with colon involvement. Severity of symptoms is typically proportional to disease activity.2,55,56

Less frequently, the arthritis affects primarily the spine. Symptoms are low back pain and stiffness, with eventual limitation of motion. This EIL occurs predominantly in men with HLA-B27 and is fairly indistinguishable from typical ankylosing spondylitis. In fact, it may antedate the bowel symptoms by several years. There is probably a consistent underlying factor in both the progression of ankylosing spondylitis and IBD.2,55,56

Skin manifestations are also common, being seen in approximately 15% of patients. Typical lesions are erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and aphthous ulcerations. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis occurs in approximately 10% of patients.2,55,56

Serious liver disease (i.e., sclerosing cholangitis, chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis) is also a common EIL, affecting 3% to 7% of the patients with IBD. It probably relates to the increased endotoxin load associated with IBD. If patients are demonstrating liver enzyme abnormalities, hepatoprotection appears indicated, with botanical medicines such as Silybum marianum (i.e., silymarin) and curcumin.57–59

Other common EILs are as follows2,55,56:

Malnutrition

Many nutritional complications occur during the course of IBD.60–62 Because these complications can have a significant influence on the morbidity and perhaps also the mortality of these patients, every effort should be made to ensure optimal nutritional status. The major mechanisms that contribute to nutritional depletion in patients with IBD are listed in Box 181-1.

BOX 181-1 Causes of Malnutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

• Decreased absorptive surface due to disease or resection

• Bile salt deficiency after resection

• Drugs (e.g., corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, cholestyramine)

Increased secretion and nutrient loss

Increased utilization and increased requirements

A decreased food intake is the most important mechanism of nutritional deficiency in patients with IBD, and a deficient calorie intake is the most common nutritional deficit in patients requiring hospitalization. Often the patient feels significant pain, diarrhea, nausea, and/or other symptoms after a meal, resulting in a subtle diminution in dietary intake. Protein-calorie malnutrition and associated weight loss are prevalent in 65% to 75% of patients with IBD.60

• Stimulate protein catabolism

• Decrease the absorption of calcium and phosphorus

• Increase the urinary excretion of ascorbic acid, calcium, potassium, and zinc

• Increase blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and serum cholesterol levels

• Increase the requirements for vitamin B6, ascorbic acid, folate, and vitamin D

Sulfasalazine has been shown to have the following effects63:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree