Humor as a Teaching Tool in Shoulder Arthroscopy

In the early 1990s, the shoulder establishment was laughing at arthroscopic shoulder surgeons, whom they viewed as a pitiful little band of dreamers whose goal of achieving strong arthroscopic repairs for instability and rotator cuff tears would always remain hopelessly out of reach. I recognized that humor, particularly when it was endogenous and self-deprecating, got people’s attention and could be a useful teaching tool. Furthermore, humor could turn a dry subject (such as shoulder biomechanics) into a fun experience. So there were now two reasons to employ humor in my teaching efforts.

So, as Will Rogers or some other famous cowboy must have said, “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” I took his advice and decided to encourage people to laugh at me just to get them to listen to me. As a mechanical engineer by training (prior to medical school), I knew that there were some mechanical concepts that were accepted as dogma in the shoulder that were absolutely wrong. Replacing those concepts with mechanically sound principles (balanced force couples, margin convergence, etc.) would fundamentally change the way we approached the shoulder, particularly the rotator cuff. But getting people to listen and getting people to understand such dry and esoteric topics was not going to be easy.

When I was a kid in the 1950s, there was a black-and-white television show every Saturday morning that was called “Watch Mr. Wizard.” Mr. Wizard was an amateur scientist named Don Herbert. In the show, he would teach complex scientific concepts to the kids in his neighborhood by means of simple experiments that could be conducted in his kitchen or his garage, using everyday tools and utensils from his home. To me, the show was fascinating, and it made science understandable and fun. Part of the fun was Mr. Wizard’s style; he employed a great deal of good-natured humor and he encouraged the kids to develop their own conclusions based on the experiments he showed them.

In late 1991, I was preparing a talk for the AANA (Arthroscopy Association of North America) Specialty Day Meeting, to be held a few months later at the AAOS (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons) venue in San Francisco. I had been assigned the topic “Biomechanics of the Rotator Cuff.” As I tried to develop my ideas, I drew a blank.

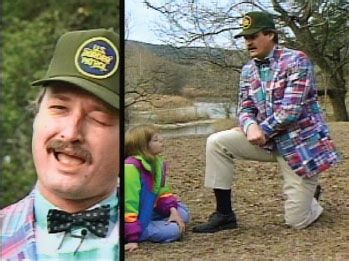

Sitting at my desk, frustrated by the impossible task of making a dull subject interesting, I hit upon an idea. I would be the eccentric, good-humored, self-deprecating “Mr. Wizhart” (Wizhart/Burkhart—get it?). My kids (Zack and Sarah) and I filmed a black-and-white “Mr. Wizhart” segment on “Minimal Surface Area” and its effect on the behavior of rotator cuff tears. At the meeting in San Francisco, I didn’t tell anyone what I was going to do. When I was introduced, I went to the podium and stated that I would show a self-explanatory video on the biomechanics of the rotator cuff. I turned on the video. Initially there was a stunned silence as the goofy introductory music began to play. Then there was a loud collective roar of laughter from the audience as Mr. Wizhart began to teach them. Orthopaedic surgeons do not usually laugh at lectures, even when the speaker tells a joke. So when I heard wave after wave of belly laughs, I knew I was onto something. The arthroscopic shoulder surgeons had a message, and they had a voice—and now they had an eager audience (Fig 29.1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree