TCAs are effective in GAD. Imipramine (Tofranil) has shown efficacy comparable to alprazolam. These have a greater side-effect burden, especially sedation and anticholinergic effects, compared to SSRIs or buspirone, and slower onset of action compared with benzodiazepines.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as phenelzine (Nardil) and tranylcypromine (Parnate), are also effective, but their complexity of drug and food interactions makes them unsuitable for general medical practice.

Other medications. Hydroxyzine (Atarax or Vistaril), an antihistamine, is superior to placebo in GAD and has a rapid onset of effect. However, its utility is limited by its sedative properties and relatively low-antianxiety properties compared with benzodiazepines. χ-Blockers may be helpful for symptomatic relief of tremor, but do not have antianxiety properties.

Psychotherapy

Studies clearly demonstrate that various forms of psychotherapy are helpful in treating GAD. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is superior to nondirective or supportive types of psychotherapy. Biofeedback and progressive relaxation can be helpful, especially in patients with significant complaints of muscle tension, pain, or insomnia. Referral to a psychologist or licensed counselor with specific training in these forms of psychotherapy is appropriate when considering these treatments.

Referral to a psychiatrist should be considered in cases with comorbid psychiatric disorders or when the patient has not responded to several attempts at treatment by the primary care physician. Patients with substance abuse problems should be referred to a substance abuse counselor for treatment directed at the substance abuse disorder.

PANIC DISORDER AND AGORAPHOBIA

Clinical Presentation

Panic attacks typically begin without warning. Pounding heart and dyspnea are common first symptoms, rapidly joined by dizziness or light-headedness, diaphoresis, light-headedness or faintness, chest pressure, and a sense of “impending doom,” or imminent death. The symptoms typically build to a peak over 10 to 30 minutes, and resolve over the next 30 to 60 minutes, on average. When their panic attacks begin, patients most commonly present to their family physician’s office or to the emergency department. Patients will most commonly describe the physical sensations first, rather than fearfulness or anxiety. With the attacks comes an intense need to escape the immediate situation, whatever it is. Phobic avoidance develops from this, as the patient gradually restricts his or her range of activities to exclude those settings in which attacks have occurred, where help might not be immediately available, or from which they might not be immediately able to escape in the event of an attack. Phobic avoidance that causes significant levels of distress or interference in the patient’s life is diagnosed as agoraphobia. Up to two thirds of PD patients have some degree of phobic avoidance.7

Diagnosis (Based on DSM-5 Criteria)

Panic Disorder

Panic attacks are characterized by the abrupt onset of intense fear that peaks within 10 to 30 minutes of onset, and is associated with at least four autonomic symptoms, including palpitations, sweating, trembling, dyspnea, choking, chest pain, nausea, dizziness, depersonalization, paresthesias, hot or cold flashes, and fear of dying. Diagnosis requires recurrent panic attacks and either 1 month of behavior change in response to the attacks or persistent worry about additional attacks or their consequences. Panic attacks should not be due to a general medical problem or the direct effect of a substance (e.g., amphetamines). Routine laboratory screening for general medical problems at the time of initial presentation should include basic electrolytes, calcium (hypocalcemia due to hypoparathyroidism causes tetany and tremor; can be a complication of thyroid surgery), random glucose (hypoglycemia), thyroid-stimulating hormone (hyper- and hypothyroidism), and urine drug screen. Twelve-lead EKG is usually obtained in the ED setting. This along with physical examination is generally sufficient to reassure the patient.

Sometimes however, more extensive evaluation to rule out a cardiac event may occur. Patients not reassured by extensive evaluation should be assessed for somatic symptom and related disorders. Isolated panic attacks can also occur in the context of other psychiatric conditions, most commonly other anxiety disorders and depressive disorders.

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is most commonly seen in patients with PD. Diagnosis requires the presence of anxiety in situations where escape is difficult or help is unavailable. Such situations are avoided, are endured with marked distress, or require a companion to be tolerated. Avoidance must not be explainable by the existence of another mental disorder. Although panic attacks are the most subjectively distressing aspect of PD to patients, severe agoraphobia can be the most disabling and the most treatment-resistant part of their illness. Patients whose agoraphobia does not improve with successful medical treatment of their panic attacks should be referred for CBT.

Treatment

In the emergency department or the office, offering patients a medical explanation and a diagnostic label for their experience can be very reassuring and therapeutic (“The workup is OK. What seems to have happened is you had a panic attack, sort of an ‘adrenaline flood’ in the brain”). It is not helpful to minimize or demean their experience (“it was just a panic attack”)—after all, to the patient, it felt like they really were about to die! If a medical cause for the panic attack is found, management begins with treatment directed at this condition. Dietary recommendations, such as the avoidance of nicotine, caffeine, and other stimulants, are helpful.6

Medical Therapy

The primary goal of treating PD is preventing recurrence of spontaneous panic attacks. Alprazolam, because of its rapid onset, can be effective in aborting a panic attack once it has begun, especially if taken sublingually. Patients with infrequent isolated panic attacks may require only prn doses of benzodiazepines, but patients with PD typically require daily medications to prevent recurrence. Effective treatment should be continued until patients are panic free for at least 6 to 12 months. Medication should be tapered slowly to avoid withdrawal symptoms or rebound panic attacks. Recurrence rates are greater than 50% after medication discontinuation, so ongoing maintenance therapy is commonly required. Buspirone and β-blockers are not effective in PD. Many patients with PD are sensitive to the side effects of antidepressant medications such as SSRIs and TCAs, so treatment should be initiated with small doses and gradually titrated upward to therapeutic doses.

SSRIs are first-line medications in PD, alone or in combination with benzodiazepines. Fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), and paroxetine (Paxil) are effective. Other SSRIs, including venlafaxine extended release (Effexor XR) and citalopram (Celexa), can also be effective.12 Full antidepressant doses are required, beginning with half of the initial dose for the first week then increasing to the first target dose. Effective doses differ for each drug (see Table 5.1-2).

The efficacy of the TCAs is well-established, and they are considered second-line if SSRIs fail or are not tolerated. Imipramine (Tofranil), desipramine (Norpramin), and clomipramine (Anafranil) are effective in PD. The initial starting dose should be 25 mg at bedtime and increased by 25 mg every 4 to 7 days as tolerated. Doses of 150 mg per day are usually required. The dosage may be slowly increased up to 300 mg per day if needed.

Common SSRIs in Anxiety Disorders |

Drug | Starting dose | Target dose |

Fluoxetine (Prozac) | 10–20 mg QAM | 20–60 mg |

Sertraline (Zoloft) | 25–50 mg QAM | 50–200 mg |

Paroxetine (Paxil) | 10–20 mg QAM | 20–60 mg |

Citalopram (Celexa) | 10–20 mg QAM | 20–60 mg |

Escitalopram (Lexapro) | 5–10 mg QAM | 10–20 mg |

Venlafaxine XR (Effexor XR) | 37.5 mg QAM | 75–225 mg |

Nortriptyline (Pamelor) is also very effective, and may be better tolerated; doses of 75 to 150 mg per day are used. An advantage of the TCAs is the ability to monitor blood levels within defined therapeutic ranges. Three weeks of treatment at an adequate dose is usually necessary before panic suppression is achieved.

High-potency benzodiazepines are highly effective in the treatment of PD, with efficacy similar to that of the SSRIs and TCAs. Compared with GAD, higher doses of benzodiazepines are required in PD (see Table 5.1-1). Clonazepam is preferred for its longer duration of action, allowing less frequent doses and less risk for rebound panic between doses. As a rule, low doses should always be started, then gradually titrated upward to the lowest dose that provides the best clinical effect. For patients with severe symptoms, it may be indicated to initiate treatment with a benzodiazepine for rapid symptom relief at the same time that an SSRI or TCA is started, then gradually to reduce the benzodiazepine to prn use after a few weeks.

Most patients who take benzodiazepines maintain their therapeutic benefit on a stable dose over time. Problems of misuse or abuse of benzodiazepines are probably limited to patients with histories of alcohol or drug abuse, or who increase their too-low medication doses on their own in an attempt to self-medicate (“pseudo-addiction”). Mood symptoms should be followed, as clonazepam can sometimes cause depressed mood, and alprazolam can occasionally cause excitation or rarely mania.

MAOIs, such as phenelzine (Nardil) or tranylcypromine (Parnate), may be even more effective than the tricyclics in resistant cases. Because of the dietary restrictions and the potential for drug interactions, these drugs are not the first line of therapy and are not generally recommended in the primary care setting.

Psychotherapy

CBT is effective in the treatment of PD and has been shown to increase the likelihood that patients can eventually reduce and even discontinue benzodiazepine treatment. The primary behavioral techniques include breathing retraining, relaxation training, and exposure to somatic cues, in which the patient is taught to recognize and restructure their interpretations of their physical symptoms. This form of therapy is effective in both group and individual settings.

Treatment involving gradual exposure of the agoraphobic patient to feared situations is essential if agoraphobia is to be overcome. Focused CBT is more effective than nonspecific or purely supportive interventions in this regard. Supportive interventions and patient education are, however, helpful in encouraging the patient to undergo and work in therapy and confront these situations.

Referral to a psychiatrist should be considered in cases with comorbid psychiatric disorders or when the patient has not responded to several attempts at treatment by the primary care physician. Patients with substance abuse problems should be referred to a substance abuse counselor for treatment directed at the substance abuse disorder.

Online Provider Tools and Patient Education Resources

For clinicians, the American Psychiatric association has an extensive list of online rating scales useful for diagnosis and severity rating at their Web site http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures

Bibliotherapy for Patients

• The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook by Edmund J. Bourne

• The Feeling Good Handbook by David R. Burns

• The Anxiety Disease by David V. Sheehan

Web Sites for Patients

• www.healthyminds.org—Patient Education site of the American Psychiatric Association (APA)

• www.adaa.org—Anxiety and Depression Association of America

• www.nami.org—National Alliance on Mental Illness (general information)

• www.ocfoundation.org—The Obsessive Compulsive Foundation (for OCD)

REFERENCES

1. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2012;21(3):169–184.

2. Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, et al. Functional impact and health utility of anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Med Care 2005;43(12):1164–1170.

3. Katon W. Panic disorder: relationship to high medical utilization, unexplained physical symptoms, and medical costs. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57(Suppl 10):11–22.

4. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146(5):317–325.

5. Martin EI, Ressler KJ, Binder E, et al. The neurobiology of anxiety disorders: brain imaging, genetics, and psychoneuroendocrinology. Clin Lab Med 2010;30(4):865–891.

6. Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66(7):785–795.

7. Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, Mcquaid JR, et al. Development of a brief diagnostic screen for panic disorder in primary care. Psychosom Med 1999;61(3):359–364.

8. Means-Christensen AJ, Arnau RC, Tonidandel AM, et al. An efficient method of identifying major depression and panic disorder in primary care. J Behav Med 2005;28(6):565–572.

9. American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Culpepper L. Use of algorithms to treat anxiety in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(Suppl 2):30–33.

11. Craske MG, Roy-Byrne PP, Stein MB, et al. Treatment for anxiety disorders: efficacy to effectiveness to implementation. Behav Res Ther 2009;47(11):931–937.

12. Baldwin D, Woods R, Lawson R, et al. Efficacy of drug treatments for generalized anxiety disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2011;342:d1199.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by persistent depressed mood and lack of interest and pleasure nearly every day over at least 2 consecutive weeks.1 Depressed mood can be ascertained by either self-report or observation by a family member (Table 5.2-1). Mood may be irritable or sad in children and adolescents. The health care burden of MDD is comparable to that of cardiovascular diseases. MDD is the second leading cause of Years Lived with Disability worldwide.2 Family physicians treat more depression than any other professional.3

Epidemiology

Twelve-month prevalence of MDD in the United States is approximately 7% with females experiencing 1.5 to 3 times higher rate than males.1 Although the peak age of onset for depressive disorders is in the third decade, no age group is immune to the onset of depression. Late-life depression with vascular etiology is being increasingly recognized.

Pathophysiology

The most replicated biologic finding in depression is elevated stress levels.4 Bioamine hypothesis postulates decreased levels or activity of norepinephrine and/or serotonin responsible for development of depressive symptoms.4 This has resulted in developing treatment strategies targeting these two neurochemical systems. Other, less specific findings include decreased latency to first rapid eye movement sleep phase and hypoperfusion of the frontal lobes in patients with MDD.

Cerebrovascular disease is increasingly recognized to have a significant relationship to mood disorders in elderly individuals. Deep white matter hyperintensities (DWMHs) have been associated with chronicity of geriatric depression and its poor response to antidepressants.5

Etiology

Higher prevalence of depression in first-degree relatives of patients with major depression and higher concordance rates in monozygotic twins point to a genetic role in the etiology of depression. Exposure to stressful life events such as the death of a child or abuse can predispose patients to develop depression. Patients with short allele of serotonin transporter gene have been found to be more susceptible to the adverse impacts of stressful life events.6 Thus, the etiology of depression has both genetic and environmental factors.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

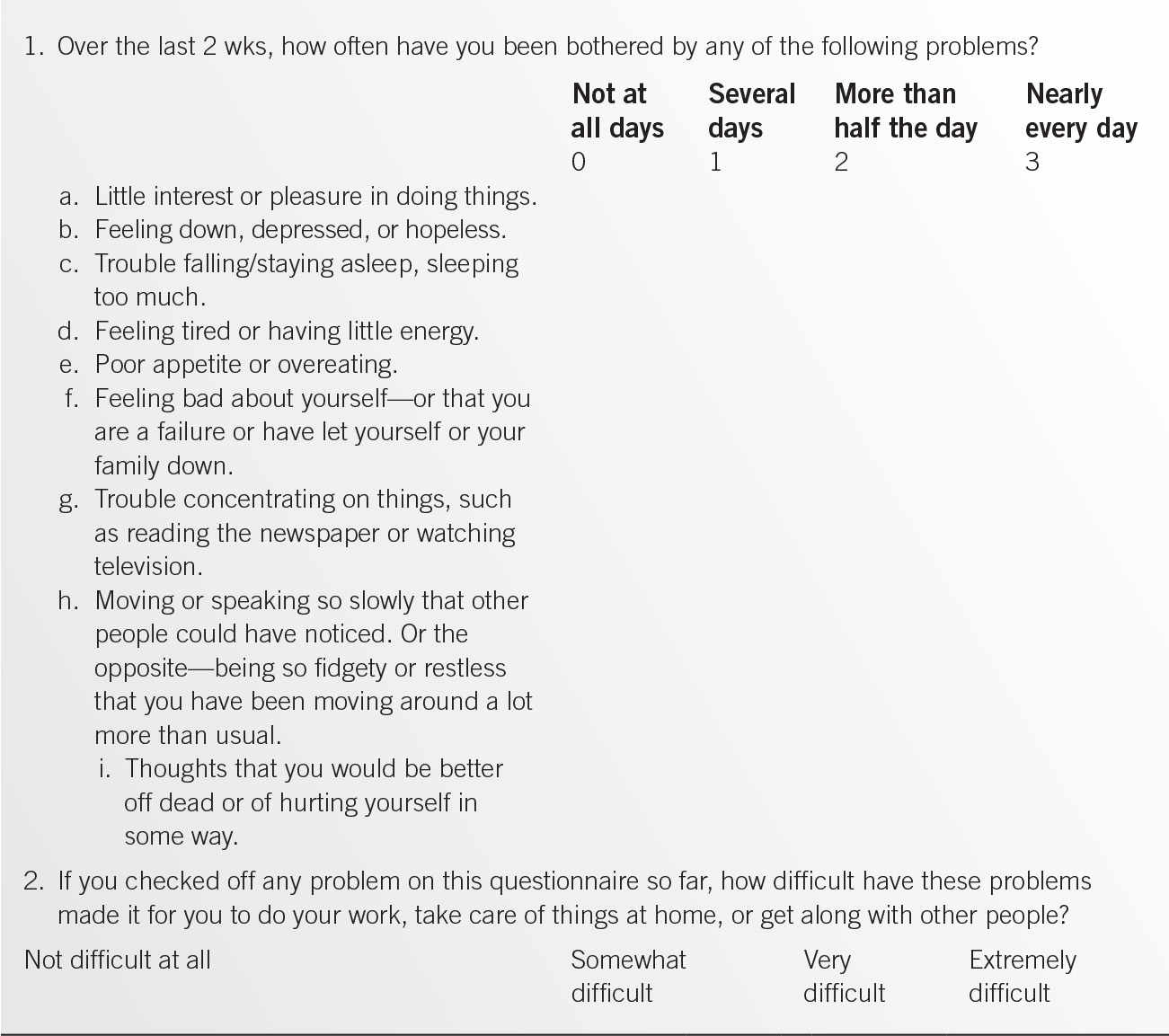

Diagnosis of depression is mainly clinical. DSM-5 criteria for MDD are easily remembered using a mnemonic “SIGMECAPS” (Table 5.2-2). For the diagnosis of MDD, one has to suffer from five (or more) of the nine symptoms nearly every day for at least 2 consecutive weeks and represent a change from previous functioning.. One of the symptoms has to be either depressed mood or markedly decreased interest in pleasurable activities. Several instruments can be used for detection of depression, including the Beck Depression Inventory,7 Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),8 and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology9 (QIDS), which not only assesses the severity of depression but also serves as a diagnostic tool.

Elderly patients often present with somatic complaints to primary care providers and often deny mood symptoms. Corroborative history from family members and friends can be invaluable in making a diagnosis in poor historians. Denial of symptoms may occur for multiple reasons, including stigma, negligence, and the fear of consequences of a diagnosis on their occupation and insurance status. Many older patients present with what otherwise looks like a depressive syndrome but steadfastly deny they have depression. This has been referred to as “masked depression” or “depression without sadness.”10

Comorbidity is a rule rather than an exception. Anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and other medical conditions complicate the course and treatment of depression and increase the risk for suicide.

Diagnostic Criteria for MDD Based on DSM-5 Criteria5 |

Sustained low or depressed Mooda

Sleep disturbance, decreased or increased

Decreased Interest or pleasurea

Feeling worthless or Guilt

Fatigue or loss of Energy

Diminished Concentration

Appetite disturbance, weight loss or gain (5% change in a month)

Psychomotor agitation or retardation

Recurrent thoughts of death, Suicidal ideation

aPresence of five or more of the above during the same 2-week period with at least one symptom of either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure.

Physical Examination

Physical examination is geared toward ruling out medical conditions such as hypothyroidism, dementia, and parkinsonism that can manifest with depression.

Classification

Depression is a heterogeneous condition and is classified into MDD, persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), disruptive mood regulation disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, depression secondary to general medical condition, substance-induced mood disorder, other specified depressive disorder, and unspecified depressive disorder. Persistent depressive disorder is a low-grade depression that is present most of the day, for more days than not, for more than 2 years. Symptoms associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder must be present in the final week before onset of menses and start to improve within a few days after the onset of menses. Substance-induced mood disorder usually has onset within a month of intoxication or withdrawal from substance use. MDD can often be complicated with psychotic symptoms. It is also further classified into primary and secondary depression and depression with or without melancholic symptoms. Yet another classification is based on the presence or absence of atypical features such as hyperphagia, leaden paralysis, hypersomnolence, and hypersensitivity to rejection. This distinction is important as patients presenting with atypical features might respond better to monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as phenelzine.

Differential Diagnosis

Bipolar disorder can manifest with depressive episodes. A history of mania in the past, family history of bipolar disorder, or past treatment with mood stabilizers alerts clinicians about the possibility of bipolar disorder. This distinction is essential to avoid the risk of switching to mania by initiating monotherapy with antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder. Although the risk of manic switch is most robust with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), it is also seen with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other agents such as venlafaxine and bupropion.

TREATMENT

Behavioral

The treatment of MDD includes both pharmacologic and psychologic interventions. Cognitive–behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy are the most studied therapies for depression.11 Patients who respond to psychologic intervention are usually in the range of mild to moderate symptom severity. The combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy has resulted in better results than either treatment alone.

Medications

Several classes of antidepressants are available, including MAOIs, TCAs, SSRIs, and mixed antidepressants. SSRIs are often considered the first-line treatment for depression due to their relatively better safety profile and ease of administration. The common doses of antidepressants are outlined in Table 5.2-3.

Most of the antidepressants have comparable efficacy at 50% to 60% response rate.11 The selection of an antidepressant is therefore dependent not on efficacy per se but on specific factors such as the side-effect profile, potential drug interactions, cost, ease of use, and formulation combined with patient-specific information such as comorbid medical conditions, and possibly the type of depressive symptomatology. TCAs should be used with caution in patients with cardiac disease. Similarly, TCAs should be avoided in people with dementia, narrow-angle glaucoma, urinary retention, and bowel obstruction because of their anticholinergic activity. The presence of a seizure disorder may preclude the use of bupropion.

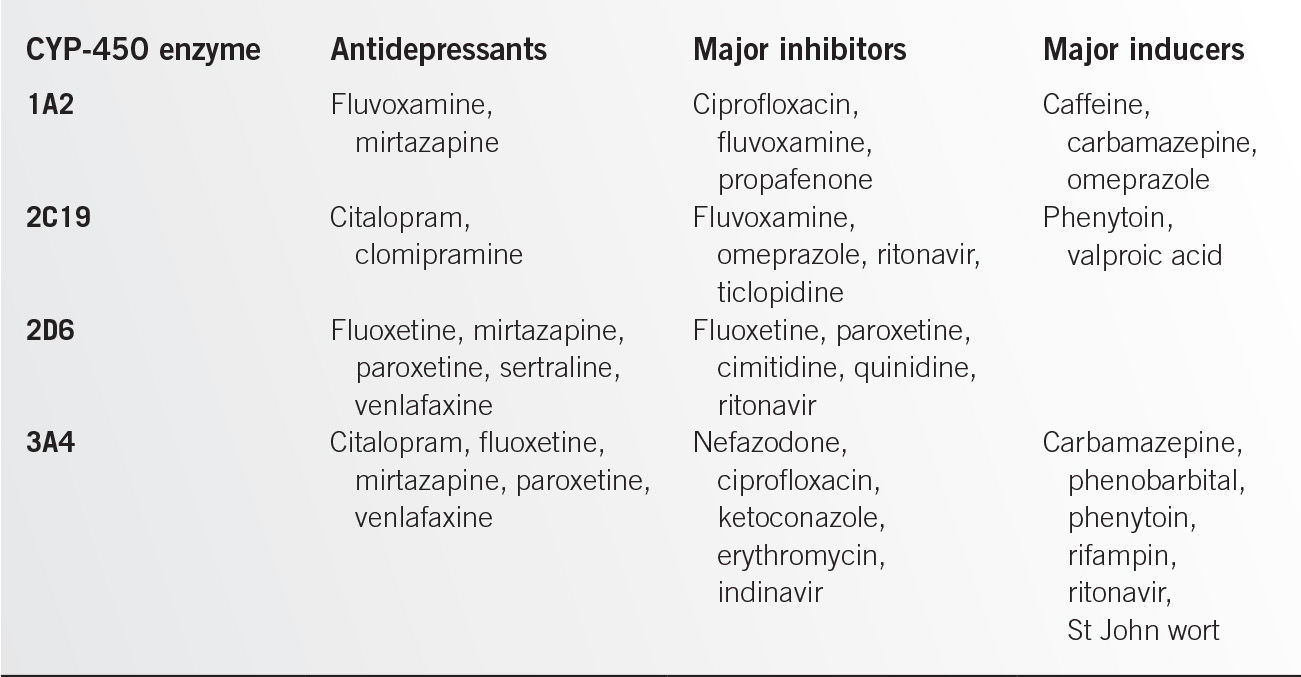

Baseline symptoms often can help with selection of antidepressants. For example, “activating” antidepressants such as fluoxetine and bupropion may be prescribed for patients with hypersomnia. Likewise, mirtazapine may be of value for patients with insomnia and anorexia. Drug interactions with concomitant medications may also inform which antidepressants to avoid (Table 5.2-4).

Doses of Common Antidepressants |

Medication | Starting dose (mg/day) | Therapeutic dose (mg/day) |

TCAs |

|

|

Amitryptyline | 25–50 | 100–300 |

Nortriptyline | 25 | 50–200 |

Imipramine | 25–50 | 100–300 |

SSRIs |

|

|

Citalopram | 10–20 | 20–60 |

Fluoxetine | 10–20 | 20–80 |

Sertraline | 25–50 | 100–200 |

Paroxetine | 10–20 | 20–50 |

Escitalopram | 10 | 20 |

MAOIs |

|

|

Phenelzine | 45 | 180 |

Tranylcypromine | 20 | 30–60 |

Mixed antidepressants |

|

|

Mirtazapine | 7.5–15 | 15–45 |

Venlafaxine XR | 37.5 | 75–225 |

Bupropion SR | 100–150 | 300 |

Duloxetine | 20–30 | 60 |

Special Therapy

• Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been employed successfully in the management of MDD. It is known to have 80% acute response but suffers from lack of persistent effects and often necessitates maintenance treatment.12 ECT is safe in elderly patients and often employed in patients with extreme anorexia, failure to thrive, and those with intractable suicidal thoughts.12

• Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation has recently received FDA approval for those with treatment-resistant depression.

• Augmentation of antidepressants: augmentation with have been used successfully in treating depression unresponsive to single antidepressants. Increasing use of atypical antipsychotics as augmentation agents is seen.

Risk Management

A major risk associated with depression is the high rate of suicide. Approximately 15% patients suffering from depression lose life due to suicide.13 The rates of suicide are highest among white men older than 60 years of age. Direct questioning and detailed past history can inform clinicians about potential suicide risk in a patient. SADPERSONS is a useful mnemonic for assessment of suicide risk in practices (Table 5.2-5).

Patient Education

Patients need to be educated about the common symptoms of depression and the need for treatment. It must be emphasized that depression is treatable and patients should be counseled not to stop antidepressants until they consult with their physicians. Many resources are available on the internet about depression.14,15

Follow-Up

An increase in suicide rate is seen while recovering from an episode of depression, as the somatic symptoms of depression (sleep, appetite, and energy) are the first to improve and the cognitive symptoms (low self-esteem, guilt, and suicidal thoughts) are slower to improve. This increased risk of suicide during recovery necessitates continued monitoring while treating patients for depression.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Late-life depression. There are several reasons depression in elderly individuals is difficult to diagnose. Older adults are less likely to endorse symptoms of depression than younger patients and often reject the diagnosis of depression. They are more likely to endorse low energy, anhedonia, and other somatic complaints, which are difficult to differentiate from general medical conditions. Likewise, there is a tendency to explain away depressive symptoms that are expressed as components of normal aging, grief, physical illness, or even dementia. Subsyndromal depression is much more common than in the elderly. To complicate matters further, suicide rates in elderly are the highest of any age group.16 A high degree of suspicion and specific inquiry is necessary for its detection and treatment. Specific rating scales such as the geriatric depression scale are useful in screening for late-life depression (Table 5.2-6).17 Even a four-item version of the geriatric depression scale has high sensitivity for detection of depression and could be very helpful in busy practices.

Assessment Tool for Suicide Risk |

S | Male sex |

A | Age (young/elderly) |

D | Depression |

P | Previous attempts |

E | ETOH |

R | Reality testing (impaired) |

S | Social support (lack of) |

O | Organized plan |

N | No spouse |

S | Sickness |

Geriatric Depression Scale |

Choose the best answer for how you have felt over the past week:

1. Are you basically satisfied with your life? YES/NO

2. Have you dropped many of your activities and interests? YES/NO

3. Do you feel that your life is empty? YES/NO

4. Do you often get bored? YES/NO

5. Are you in good spirits most of the time? YES/NO

6. Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you? YES/NO

7. Do you feel happy most of the time? YES/NO

8. Do you often feel helpless? YES/NO

9. Do you prefer to stay home, rather than going out, doing new things? YES/NO

10. Do you feel you have more problems with memory than most? YES/NO

11. Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now? YES/NO

12. Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now? YES/NO

13. Do you feel full of energy? YES/NO

14. Do you feel that your situation is hopeless? YES/NO

15. Do you think that most people are better off than you are? YES/NO

Items in bold constitute the four-item scale.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6.

3. Schumann I, Schneider A, Kantert C, et al. Physicians’ attitudes, diagnostic process and barriers regarding depression diagnosis in primary care: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Fam Pract 2012;29(3):255–263.

4. Roy A, Campbell MK. A unifying framework for depression: bridging the major biological and psychosocial theories through stress. Clin Invest Med 2013;36(4):E170–E190.

5. Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ, Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18(9):963–974. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.20.

6. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003;301(5631):386–389.

7. Rogers WH, Adler DA, Bungay KM, et al. Depression screening instruments made good severity measures in a cross-sectional analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58(4):370–377.

8. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32(4):345–359.

9. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(5):573–583.

10. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012;37(4):851–864. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.306.

11. Lampe L, Coulston CM, Berk L. Psychological management of unipolar depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2013;(443):24–37. doi: 10.1111/acps.12123.

12. Lisanby SH. Electroconvulsive therapy for depression. N Engl J Med 2007;357(19):1939–1945.

13. Gonda X, Fountoulakis KN, Kaprinis G, et al. Prediction and prevention of suicide in patients with unipolar depression and anxiety. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2007;6:23.

15. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: http://www.afsp.org/

16. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry 2002;52(3):193–204.

17. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, ed.Clinical gerontology: a guide to assessment and intervention. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 1986:165–173.

|

The prevalence of alcohol use disorders in primary care outpatient populations may be as high as 20%. The cost to society of these problems is staggering. Each year in the United States, alcoholism is responsible for 88,000 deaths and costs of $223.5 billion dollars.1,2 Family physicians are in a unique position to identify and treat these problems.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

• Alcoholism is a primary, chronic neurobiologic disease with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired use of the drug alcohol, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.3

• Alcoholism or alcohol dependence is best defined by a loss of control over drinking.

• Because of the defense mechanism of denial, patients are often not consciously aware of their loss of control, and tend to minimize the amount, frequency, and consequences of their alcohol consumption.

• Alcohol abuse refers to the harmful use of alcohol, usually meant for patients who are having consequences for their drinking but have not yet lost the ability to control their alcohol use.

• Physical dependence is a state of physiologic adaptation that is manifested by a drug class-specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation or rapid dose reduction of a drug or by administration of an antagonist.3 In the case of alcoholism, physical dependence is sometimes but not always seen in the presence of alcoholism or alcohol dependence.

• Low-risk drinking is a term defined by not more than two drinks (a drink equals 1.5 oz liquor, or 12 oz beer, or 6 oz of wine) daily and no more than five in any given day for a male and no more than one drink daily for women with no more than three in any given day.

• Exceeding these limits is considered heavy drinking.

• Heavy drinking is drinking in excess of maximum limits on a regular basis.

• At-risk drinking is heavy drinking that does not meet criteria for alcohol use disorder and places an individual at higher risk for developing alcohol-related problems.3

Epidemiology

• Approximately two thirds of all American adults drink alcohol.

• Each year, 13.8 million Americans develop problems from drinking.

• Lifetime prevalence for alcoholism is 17.8% for men and 12.5% for women.3

• The prevalence of all alcohol use disorders is highest in young adults between the ages of 18 and 29.

• Incidence of drinking problems is greater for men than for women and declines with age.

• For those who begin drinking before the age of 15, the rate of progression to alcoholism is 15 times that of those who begin drinking at age 21. In older adults, the rates drop off precipitously.

• One-third of adolescent drinkers will transition to alcohol use disorders.

• Alcohol use disorders can occur in up to50% of patients admitted to a community hospital and between25% and 27% of patients seen in primary care practice visits.

• Characteristics known to influence the epidemiology of alcoholism include gender, age, family history, marital status, employment status, and occupational/educational status.

• The risk of alcoholism for the child of an alcoholic is approximately 50%. Single persons have a higher risk than those who are married.The unemployed and less educated also have a higher risk.4

Pathophysiology

• Alcoholism is a brain disease. A disorder in the reward system of the mesolimbic system of the brain results in dysregulated dopaminergic neurons.

• This abnormality results in craving for alcohol and impairs individuals’ ability to control their use of this drug. In addition to dopamine, multiple neurotransmitter systems are involved in this process, including the γ-aminobutyric acid system, serotonin system, N-methyl-D-asparate system, and glutamate. These systems modulate the effect of the drug, and the reward system determines the craving for it.

Etiology

• Family and twin studies show that there is a genetic component to a predisposition to alcoholism.

• Patients who develop alcoholism without a family history of the disease or those who do not develop alcoholism despite a strong family history of the disease speak to the environmental influences that must also play a part.

DIAGNOSIS

Screening

A primary screen for alcohol-related problems may be done as part of the review of systems or as part of a routine visit. Patients who drink at all, no matter how infrequently, should be asked questions from the “CAGE,” a brief and practical primary screening tool for alcohol abuse. The term CAGE is an acronym for the key word in each of the four questions below. Any positive response justifies a more in-depth screen.

• Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?

• Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

• Have you ever felt guilty about your drinking?

• Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover (“eye opener”)?

A slightly longer but more accurate alternative screening test is the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Table 5.3-1)5. AUDIT questions are provided below along with the scoring values. Typically, a total of eight points or more on the AUDIT is suggestive of alcohol dependence.

DSM-5 Diagnosis Criteria for Alcohol Use Disorder6

A. A problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period.

1. Alcohol is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

2. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use.

3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use alcohol, or recover from its effects.

4. Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol.

5. Recurrent alcohol use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, home, or school.

The AUDIT Questionnaire |

1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?

1. Never

2. Monthly or less

3. Two to four times a month

4. Two to three times a week

5. Four or more times a week

2. How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?

1. 1 or 2

2. 3 or 4

3. 5 or 6

4. 7 or 9

5. 10 or more

3. How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion?

1. Never

2. Less than monthly

3. Monthly

4. Weekly

5. Daily or almost daily

4. How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started?

1. Never

2. Less than monthly

3. Monthly

4. Weekly

5. Daily or almost daily

5. How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected from you because of drinking?

1. Never

2. Less than monthly

3. Monthly

4. Weekly

5. Daily or almost daily

6. How often during the last year have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session?

1. Never

2. Less than monthly

3. Monthly

4. Weekly

5. Daily or almost daily

7. How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking?

1. Never

2. Less than monthly

3. Monthly

4. Weekly

5. Daily or almost daily

8. How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking?

1. Never

2. Less than monthly

3. Monthly

4. Weekly

5. Daily or almost daily

9. Have you or someone else been injured as a result of your drinking?

1. No

2. Yes, but not in the last year

3. Yes, during the last year

10. Has a relative, friend, doctor, or other health worker been concerned about your drinking or suggested that you should cut down?

1. No

2. Yes, but not in the last year

3. Yes, during the last year

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree