Decreased intake

Malignancy, congestive heart failure, medications, dementia, depression, grief, electrolyte disturbances, poor dentition or taste, gastric or esophageal disease, electrolyte disorders, alcoholism, financial hardship, social isolation, HIV and AIDS

Increased nutrient loss

Profuse vomiting or diarrhea, diabetes mellitus

Increased metabolic demand

Fever, malignancy, tuberculosis, hyperthyroidism, chronic infection, drug abuse (cocaine, stimulants)

Impaired absorption

Cholestasis, infection (parasitic, other), medications, pancreatic insufficiency, diabetic or HIV enteropathy, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac sprue, surgery

Weight Loss MD: A Mnemonic for Common Causes of Unintentional Weight Loss in Adults31 |

W | Wasting disease (e.g., cancer, AIDS) |

E | Eating problems or disorders (anorexia nervosa, inability to feed self) |

I | Income deprivation, Infectious (e.g., HIV, TB) |

G | Gastrointestinal problems (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, parasitic infestation, chronic diarrhea, gastroparesis, celiac disease) |

H | Hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypoadrenalism |

T | Toxic substances (e.g., alcohol, laxatives, lead, illicit drugs) |

L | Low-calorie diet (e.g., commercial weight loss programs, self-imposed diets) |

O | Oral problems (e.g., sores, ulcers, caries, poor dentition or dentures) |

S | Swallowing disorders (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson disease, progressive supranuclear palsy) |

S | Social problems (e.g., isolation, neglect, stress) |

M | Medication side effects or metabolic conditions (e.g., diabetes, thyroid disease)11 |

D | Depression or other psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder) |

AIDS: Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus

TB: Tuberculosis

• Categories of weight loss. The causes of weight loss can be divided into four major categories: decreased intake; increased nutrient loss; increased metabolic demand; and impaired absorption (Table 2.1-1). A novel way of approaching typical causes of weight loss is by using the mnemonic device “Weight Loss MD” (Table 2.1-2). Since gastrointestinal (GI) causes are frequently implicated in weight loss, it may be suitable to divide causes of weight loss into GI and non-GI causes.3 Involuntary weight loss exceeding 20% of usual, baseline weight is often associated with severe protein-energy malnutrition, nutritional deficiencies, and multiorgan dysfunction.10

Special Considerations

A tailored approach in elderly people includes greater emphasis on social and environmental factors.4,8,11,12 Unintentional weight loss in elderly people is often associated with increased morbidity and mortality.4,8,12–14 The approach in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is more comprehensive, and special attention is given to disease-specific infections, nutritional changes, psychosocial issues, and neoplasia.15–17 In the pediatric population, failure to thrive is still the most appropriate term for improper growth among infants and young children.18 Anorexia nervosa and other psychiatric or behavioral disorders are the most common causes of weight loss in older children.19

Other populations at high risk for unintentional weight loss are those suffering major burns and trauma and those with spinal cord injury, as well as patients in outpatient rehabilitation and in nursing homes due to comorbid factors such as aging and disability.20,21

History

• Initial data. Begin with open-ended, general questioning followed by a complete review of systems. How do you feel about your weight? This open-ended question provides an opportunity for patients to disclose any concerns about their weight loss and help uncover undiagnosed eating disorders. More specific questions include: Is the loss intentional? Are you dieting, taking diuretics or laxatives, or suffering from any eating disorders? A yes to any of these questions would be classified as voluntary weight loss. It is valuable to quantify the patient’s average daily or weekly intake of food and drink and total calories. Food frequency questionnaires are useful tools for the above and are best administered by registered dietitians.22 The frequency of meals, appetite changes, and difficulty with food preparation can also be elicited. Quantify tobacco, alcohol, and drug usage as these substances often replace food intake and increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies and subsequent weight loss. Focused and relevant past medical, surgical, psychiatric, and family histories will often provide clues to the underlying cause of weight loss. Ask about past bariatric or gastric bypass surgeries, previous or current mood disorders, and any history of endocrinopathies. Inquire about exercise habits—excessive exercise or forms of physical activity may hint at underlying body dysmorphic disorders.23 Medications (especially anorexiants) and herbal or vitamin supplements may also factor into weight considerations, and a detailed list of all pharmaceuticals should be obtained.2,8,13 Social factors, including stress, isolation, and the cost and effort required to prepare and consume food, can have a major impact on weight.13,24

• Specific historical data. The patient’s symptoms and complaints should direct the clinician to greater detail. Focus your history using the mnemonic device Weight Loss MD (Table 2.1-2). Ask all patients about constitutional symptoms to evaluate their general state of health: Any nausea or vomiting? Change in bowel habits? Fever? How is their appetite? Energy level?

Physical Examination

The importance of a complete physical exam in evaluating unexplained weight loss has been confirmed.6 In the pediatric population, physical findings are helpful in distinguishing causes of involuntary weight loss.25 First, quantify loss by serial weight measurements whenever possible. Measurement of vital signs, including body mass index, temperature, blood pressure, respiratory and heart rates, is always important. A more focused examination based on clues from the history is often appropriate. Physical findings such as a goiter, clubbing, hepatosplenomegaly, and/or generalized lymphadenopathy may also be relevant findings.25

Testing

• Basic laboratories. Debate continues regarding the most useful and cost-effective laboratory testing for involuntary weight loss. A simple and structured approach is best.1–4,8 The first line of testing should include complete blood count, thyrotropin (thyroid-stimulating hormone; TSH) assay, urinalysis, and fecal occult blood testing. A comprehensive chemistry panel including serum glucose, transaminases, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolytes (calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, sodium, and potassium) is essential. A chest radiograph is often included in the initial battery of tests.1

• Comprehensive analysis. Careful observation and follow-up are superior management strategies to undirected diagnostic testing.1–4,8 An initial basic evaluation can often provide reassurance regarding lack of an ominous cause to the involuntary weight loss.6 When indicated, targeted ultrasounds, upper gastrointestinal radiographs, endoscopy, and colonoscopy are the most useful second-line tests.1 National Cancer Institute or U.S. Preventive Services Task Force age-specific screening guidelines should be evaluated and up-to-date for the patient. These can be accessed on the internet at http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm.

Computed tomography and other expensive investigations are seldom beneficial in the absence of a specific indication.1,2,8 Tumor markers are third-line tests and may not be as helpful as previously thought in uncovering the cause of involuntary weight loss.14

Differential Diagnosis

The integration of history, examination, and laboratory data will usually reveal the cause of involuntary weight loss. Cancer, including gastrointestinal malignancies, accounts for 24% of cases, whereas lung cancer represents 5% of cases. Gastrointestinal diseases account for another 25% to 31%.7 Using a cancer scoring system to stratify older patients into risk categories for cancer due to unexplained, unintentional weight loss has not proven to be of value in identifying an underlying cause.5 If the initial steps in the evaluation are not conclusive, the best approach is careful observation. Follow-up examinations and testing should be done monthly for 6 months. If a physical cause exists, it will almost always be found within this period of time.1,4 If an organic cause is present, this simple approach will expose it more than 75% of the time.1,2 If an organic cause is not identified within the first 6 months, it is unlikely that one will be found.4 However, these undifferentiated patients typically do well, and assuming they do not have continued and progressive weight loss, they have an excellent overall prognosis.5 Malignancy is a significant cause of weight loss; however, a truly occult malignancy is rare, and an exhaustive search for one is neither cost-effective nor supported by the literature.1–6

TREATMENT

Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments are usually comingled in the treatment plan for unintentional weight loss.

• Nonpharmacologic treatment. Involving ancillary health care providers, such as dietitians, social workers, home health care nurses, and immediate or extended family members, is beneficial.1,4 Increasing physical activity in patients with low energy may stimulate appetite and result in modest weight gain.1,4 Nutritional supplements are a common modality in treating weight loss and often work best when used in conjunction with other treatment options.13,26 Counseling patients to consume nutritional supplements in between, rather than instead of meals, is the best approach13,26 A broad-spectrum vitamin and mineral supplement should be considered in all patients with unintentional weight loss.13,26

• Pharmacologic treatment. Several medications have been used in attempts to stave off continued weight loss and establish weight gain. Megestrol acetate is indicated for unexplained, significant weight loss in patients with AIDS.27 Recent literature has shown megestrol is also effective in weight gain among the cachectic, geriatric patients.28 Dronabinol is indicated for weight loss in patients with AIDS and in patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy.29 Other appetite stimulants or weight-gain–inducing medications include cyproheptadine, ghrelin, growth hormone, vitamin supplements, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and other mood-stabilizing drugs.11,28,30 Treatment with any medication should involve close monitoring for side effects and initially be for a short period (<3 months); further treatment depends on response and condition of the patient.26

REFERENCES

1. Evans AT, Gupta R. Approach to the patient with weight loss. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-weight-loss?detectedLanguage=en&source=search_result&search=unexplained+weight+loss&selectedTitle=1%7E150&provider=noProvider. Accessed November 4, 2013.

2. McMinn J, Steel C, Bowman A. Investigation and management of unintentional weight loss in older adults. BMJ 2011;342:d1732.

3. Proctor DD. Approach to the patient with gastrointestinal disease. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil medicine. 23rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders; 2008:840–841.

4. Alibhai SMH, Greenwood C, Payette H. An approach to the management of unintentional weight loss in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;172(6):773–780.

5. Chen SP, Peng LN, Lin MH, et al. Evaluating probability of cancer among older people with unexplained, unintentional weight loss. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010;50 (Suppl 1):S27–S29. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(10)70008-X.

6. Metalidis C, Knockaert DC, Bobbaers H, et al. Involuntary weight loss. Does a negative baseline evaluation provide adequate reassurance? [published online ahead of print November 26, 2007]. Eur J Intern Med 2008;19(5):345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.09.019.

7. Sahyoun NR, Serdula MK, Galuska DA, et al. The epidemiology of recent involuntary weight loss in the United States population. J Nutr Health Aging 2004;8(6):510.

8. Huffman GB. Evaluating and treating unintentional weight loss in the elderly. Am Fam Physician 2002;15;65(4):640–650.

9. National Cancer Institute (November 2011). “Nutrition in cancer care (PDQ)”. Physician Data Query. National Cancer Institute.

10. Bistrian BR. Nutritional assessment. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Cecil medicine. 24th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 221.

11. Zanni G, Involuntary Weight Loss – An Ignored Vital Sign in Seniors. Pharmacy Times, January 15, 2010. http://www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2010/January2010/FeatureFocusWeightLoss-0110. Accessed November 5, 2013.

12. Gazewood JD, Mehr DR. Diagnosis and management of weight loss in the elderly. J Fam Pract 1998;47:19–25.

13. Stajkovic S, Aitken EM, Holroyd-Leduc J. Unintentional weight loss in older adults. CMAJ 2011;183(4):443–449.

14. Wu JM, Lin MH, Peng LN, et al. Evaluating diagnostic strategy of older patients with unexplained unintentional body weight loss: a hospital-based study [published online ahead of print November 10, 2010]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;53(1):e51–e54. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.10.016.

15. Carter M, Hughson G. Unintentional weight loss. In: NAM, Aids map. http://www.aidsmap.com/Unintentional-weight-loss/page/1044802/. Published June 14, 2012.

16. Siddiqui J, Phillips AL, Freedland ES, et al. Prevalence and cost of HIV-associated weight loss in a managed care population. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25(5):1307–1317.

17. Tang AM, Jacobson DL, et al. Increasing risk of 5% or greater unintentional weight loss in a cohort of HIV-infected patients, 1995–2003. JAIDS 2005;40(1):70–76.

18. Olsen EM. Failure to thrive: still a problem of definition. Clin Pediatr 2006;45:1–6.

19. Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Schor N, et al. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. Chap 26. 19th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2011.

20. Demling RH, DeSanti L. Involuntary weight loss and protein-energy malnutrition: diagnosis and treatment. Medscape 2001. http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/416589_2. Accessed November 5, 2013.

21. Salva A, Coll-Planas L, Bruce S, et al. Nutritional assessment of residents in long-term care facilities (LTCFs): recommendations of the task force on nutrition and ageing of the IAGG European region and the IANA. J Nutr Health Aging 2009;13(6):475–483.

22. Liu L, Wang PP, Roebothan B, et al. Assessing the validity of a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) in the adult population of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Nutr J 2013;12:49.

23. van der Meer J, van Rood YR, van der Wee NJ, et al. Prevalence, demographic and clinical characteristics of body dysmorphic disorder among psychiatric outpatients with mood, anxiety or somatoform disorders [published online ahead of print October 27, 2011]. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66(4):232–238. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.623315.

24. Sorbye LW, Schroll M, Finne Soveri H, et al. Unintended weight loss in the elderly living at home: the aged in Home Care Project (AdHOC). J Nutr Health Aging 2008;12(1):10–16

25. Caglar D. Evaluation of weight loss in infants over six months of age, children, and adolescents. Accessed April 9, 2013. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-weight-loss-in-infants-over-six-months-of-age-children-and-adolescents.

26. Smith KL, Greenwood C, Payette H, et al. An approach to the nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of unintentional weight loss among older adults. Geriatrics & Aging 2007;10(2):91–98.

27. Medline Plus. AHFS® Consumer Medication Information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. U.S. National Library of Medicine, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a682003.html.

28. Yaxley A, Miller MD, Fraser RJ, et al. Pharmacological interventions for geriatric cachexia: a narrative review of the literature. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16(2):148–154.

29. Medline Plus. AHFS® Consumer Medication Information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. U.S. National Library of Medicine, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a607054.html

30. Berkowitz RI, Fabricatore AN. Obesity, psychiatric status and psychiatric medications. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2005;28(1):39–54.

31. Grief, SN. Weight loss. In: Paulman P, Paulman A, Harrison J, eds. Taylor’s Manual of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:47–50.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Fatigue is defined as a subjective state of lack of energy, exhaustion, or tiredness with a decreased capacity for physical or mental work, and persists despite sufficient rest.

Epidemiology

One of the most common complaints in the general population, fatigue is the chief complaint in nearly 10% of patients presenting to a primary care physician and is reported as a symptom in over 20% of all patient encounters. Women complain of fatigue approximately twice as often as men. A medical or psychiatric cause is identified in about two-thirds of cases of fatigue.1 The prognosis of idiopathic fatigue is surprisingly poor with half of patients still fatigued 6 months later.

Classification

Fatigue may be classified as acute fatigue, prolonged fatigue, chronic fatigue, and chronic fatigue syndrome. Acute fatigue is short-lived and generally attributable to physical exertion or an acute illness. Prolonged fatigue is defined as persistent fatigue lasting 1 month or longer, while chronic fatigue is defined as similar symptoms lasting 6 months or more.

Chronic fatigue syndrome is specifically defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as clinically evaluated, unexplained, persistent, or relapsing fatigue lasting 6 months or more with four or more of the following associated symptoms: impaired memory or concentration, sore throat, tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes, muscle pain, pain in several joints, new headaches, unrefreshing sleep, or malaise after exertion.2 The impairment in functioning and psychological distress is more severe in chronic fatigue syndrome than idiopathic chronic fatigue, and the prognosis is worse. Less than 10% of patients with chronic fatigue have chronic fatigue syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS

History

The clinical evaluation of fatigue is rooted in a thorough medical and psychosocial history. Allowing the patient to speak uninterrupted for the first several minutes in the interview often provides important clues. Key aspects of history include onset and nature of the fatigue, medical and psychiatric histories, family and social histories, medications and substance use, dietary and exercise habits, life events, and family relationships. A mental status examination and screening for depression should be considered if warranted by presenting symptoms.

Physical Examination

The physical examination, though often unrevealing, should include thyroid gland assessment; full cardiopulmonary examination to detect evidence of CHF, valvular disease, or chronic lung disease; full neurologic examination, including muscle strength, bulk, and tone; and examination of the lymphatic system to assess for lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory and Imaging

Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of fatigue does not often yield answers. Studies show that only about 15% of patients in primary care settings have an organic cause for their fatigue and that laboratory results rarely affect management. The following recommendations for the laboratory investigation of fatigue are adapted from guidelines developed by Dutch, Canadian, and Australian general practice groups3:

• Consider monitoring for a month after initial presentation, while initiating conservative management.

• If proceeding with laboratory evaluation, it should include complete blood count, electrolytes, glucose, liver and kidney function tests, thyroid function tests, and urinalysis.

• Clues from the history and examination may indicate the need for erythrocyte sedimentation rate, monospot, antinuclear antigen testing, or chest radiography.

Differential Diagnosis

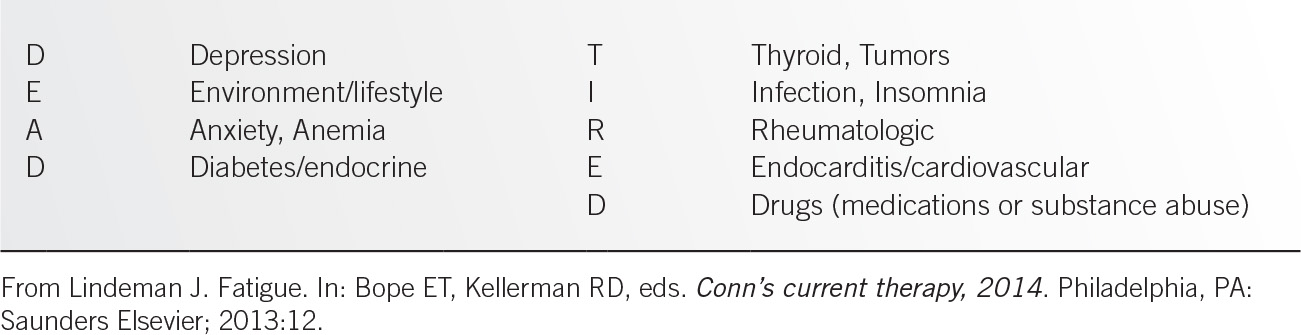

The mnemonic, DEAD TIRED (Table 2.2-1), illustrates the common causes of fatigue. Depression, environment or lifestyle issues, anxiety and anemia are among the most common causes of fatigue. Diabetes and other endocrine disorders, including thyroid disease, should be considered as well as an undiscovered tumor. Many infections, especially those of viral origin, cause fatigue, as well as insomnia and sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea. Rheumatologic disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus eythematosus, and fibromyalgia, are often accompanied by fatigue. Endocarditis, while rare, is a must-not-miss diagnosis, as are other cardiac conditions such as coronary artery disease. Finally, drugs, either prescription or of personal use or abuse, should be considered. The following medications may cause fatigue4:

• Antihistamines

• Benzodiazepines

• β Blockers

• Blood pressure medications

• Diuretics

• Glucocorticoids

• Narcotic pain medications

• Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

• Sleeping medications

• Tricyclic antidepressants

A pearl that is sometimes useful is that fatigue from organic disease is relieved by sleep and decreased activity, while fatigue from anxiety or depression may improve with exercise and is often not relieved by rest.5

TREATMENT

Behavioral

Early and active management of fatigue may prevent its progression to chronicity. When an underlying cause can be identified, this should be treated. When no disease is identified, a broader biopsychosocial strategy is necessary. This begins with acknowledgement and reassurance, along with education about the common causes and natural course of fatigue. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a brief pragmatic psychotherapeutic approach that incorporates graded increases in activity while paying attention to the patient’s beliefs and concerns. Identifying unhelpful beliefs, such as this is all due to a virus, and suggesting alternative approaches that reproduce positive outcomes can be helpful. Graded exercise therapy may also be of benefit.

Medications

If there is evidence of depression, a trial of an antidepressant is appropriate. Randomized trials have shown cognitive behavioral therapy to be equally as effective as medication for mild to moderate depression.

Referrals

Specialty referrals may be appropriate in the following situations:

• Children with chronic fatigue.

• Suspicion of severe psychiatric illness.

• Suspicion of occult malignancy.

• Evidence of significant sleep disorder.

REFERENCES

1. Rosenthal TC, Majeroni BA, Pretorius R, et al. Fatigue: an overview. Am Fam Physician 2008;78(10):1173–1179.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Atlanta, GA. http://www.cdc.gov/cfs/general/index.html. Accessed March 3, 2014.

3. Harrison M. Pathology testing in the tired patient: a rational approach. Aust Fam Physician 2008;37(11):908–910.

4. O’Connell TX. Fatigue. In: O’Connell TX, Dor K, eds. Instant work-ups: a clinical guide to obstetric and gynecologic care. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2009:76–82.

5. Ponka D, Kirlew M. Top 10 differential diagnoses in family medicine: fatigue. Can Fam Physician 2007;53:892.

|

Dizziness is a common, often frustrating, complaint encountered by family physicians. The differential diagnosis for dizziness is extensive, and frequently patients have multiple contributing etiologies. While most causes of dizziness are benign, a few may be life-threatening. However, with a thorough history and physical exam, most patients can be effectively diagnosed and serious causes ruled out.

DEFINITION

Dizziness is a general term that should be classified into four subtypes:

• Presyncope. A feeling of lightheadedness; patients note that they feel like they are “about to pass out.”

• Vertigo. A false sense of motion of the self or the environment, most often described as a spinning sensation, but also as a tilting or swaying motion. Causes include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), vestibular neuritis, migraine, and cerebrovascular attacks.

• Disequilibrium. A sense of imbalance, most often noted while walking.

• Nonspecific dizziness. A vague sense of dizziness that patients struggle to describe.

The most common type of dizziness seen in general practice is vertigo; however, the distribution of causes varies with age.1 The elderly are more likely to have multiple etiologies, and more likely to have a serious cause such as stroke.2 Younger patients are more likely to present with benign causes such as vasovagal presyncope or psychiatric conditions.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of the disorder(s) causing a patient’s dizziness is made clinically. Further testing with labs or imaging is mainly for diagnostic confirmation and for ruling out other causes.

History

An accurate, unbiased history is essential to forming the correct diagnosis. Patients should be asked to describe their dizziness in an open-ended manner, without leading questions. Historical clues help define the problem, which include:

• Triggers. Vertigo that is triggered by head position changes, such as rolling over in bed or looking up to a shelf, is characteristic of BPPV. Lightheadedness upon standing is indicative of orthostasis. While standing can trigger both BPPV and orthostasis, orthostasis will not be triggered by head position changes alone. Recent head trauma may be associated with BPPV. A need to hold on to an object or countertop to maintain balance is often seen with disequilibrium.

• Timing. The acute onset of constant, severe vertigo may be seen in vestibular neuritis/acute labrynthitis or stroke. Episodic vertigo lasting less than a minute is usually BPPV. Vertigo lasting minutes to hours is more likely Meniere disease or TIA, while vertigo associated with migraine often lasts hours to days. Presyncope is always episodic, while nonspecific dizziness is more constant in nature.

• Associated symptoms. Migraine symptoms that accompany vertigo are indicative of vestibular migraine. Ear symptoms such as tinnitus and hearing loss may be seen in Meniere disease or acute labrynthitis. Presyncope is often accompanied by sweating, nausea, and blurry vision. Neurologic symptoms are concerning for central causes such as stroke or intracranial mass. Symptoms of chest pain, palpitations, and dyspnea imply cardiac causes, but may be seen in psychiatric dizziness as well.

• Past medical history. A prior history of diabetes, hypertension, stroke, or coronary artery disease is associated with cardiovascular causes of dizziness. Long-standing, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus predisposes to autonomic and peripheral neuropathy. Patients with vestibular migraine usually have a prior history of migraine.

• Family history. Many etiologies have a familial preponderance such as migraine, BPPV, stroke, and Meniere disease.

• Medications. Anticonvulsants and antidepressants are often associated with nonspecific dizziness. Overtreatment of hypertension may lead to orthostasis.

Physical Exam

A thorough physical exam is the second essential step to diagnosis. Specific exam findings include:

• Eye and ear. Cerumen impaction, otitis media, vesicles on the tympanic membrane (herpes zoster oticus), hearing or visual changes, nystagmus

• Cardiovascular. Orthostatic blood pressure, carotid bruit, heart murmur, arrhythmia, signs of peripheral vascular disease

• Neurologic. Focal findings, such as sensory changes, abnormal Rhomberg, abnormal gait

• Specialized physical exam tests may help diagnose the cause of dizziness. If BPPV is suspected, the Dix–Hallpike maneuver is diagnostic for posterior canal BPPV, and the supine roll maneuver for lateral canal BPPV. To perform the Dix–Hallpike (DH), the patient sits with legs extended on the exam table. The patient looks up and to the side at a 45-degree angle. The examiner quickly lowers the patient to a lying position with head hanging off the exam table in the same 45-degree angle. The examiner observes the patient’s eyes, and if a typical nystagmus and vertigo occur (latency of 5 to 20 seconds, crescendo–decrescendo pattern, torsional up-beating nystagmus, and lasts less than 60 seconds), then it is a positive test for the affected ear on the side tested. The test should be repeated on the opposite side, as BPPV can be bilateral. If the DH is normal, then the supine roll maneuver should be performed. The patient lies on his back, head facing up. The examiner quickly moves the patient’s head 90 degrees to the side, and waits for horizontal nystagmus and vertigo. As with the DH, the supine roll test should be repeated on the other side.

The head-thrust and visual fixation tests are useful for differentiating between stroke and vestibular neuritis. For the head-thrust test, the examiner moves the patient’s head quickly 10 degrees to the left and right, observing for a saccade. If a saccade is present, this is indicative of a peripheral lesion causing vertigo, such as vestibular neuritis. If there is no saccade, then a central cause, like stroke or intracranial mass, is suspected. The visual fixation test is helpful in patients who have spontaneous nystagmus. Nystagmus that stops by visually focusing on an object in the room indicates a peripheral lesion. Central causes of vertigo will exhibit a nystagmus that cannot be suppressed with visual fixation.

Having a patient hyperventilate may help confirm a suspicion of nonspecific, psychogenic dizziness. In this case, hyperventilation will cause a dizziness that approximates the patient’s symptoms.

Labs and Imaging

Additional evaluation with labs and imaging is generally not necessary. However, if stroke or an intracranial mass is suspected, an MRI of the brain is the imaging of choice because it best visualizes the posterior fossa. Vascular studies such as carotid doppler or MRA of intracranial vessels may be helpful in suspected cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Audiograms are helpful for confirming Meniere disease or if there is a concern for hearing loss. In cases of suspected arrhythmia, an EKG or Holter monitoring may be indicated. Vestibular function testing is helpful in cases of vertigo where the diagnosis is unclear.

TREATMENT

Dizziness is a symptom, not a disease. Therefore, to treat dizziness, the underlying problem should be targeted. Symptomatic medications, such as meclizine, antihistamines or benzodiazepines, should be used sparingly since they can worsen vertigo. Patients with vertigo often improve because the brain adapts and compensates for the initial deficit. However, vestibular suppressant medications can block central compensation and lead to chronic dizziness. These medications often increase fall risk in elderly patients as well, and thus are best avoided.

Elderly patients usually have multifactorial, chronic dizziness that is better managed than cured. All contributing factors should be elicited and treated, and function preserved. It is essential to ensure proper hearing and vision. Gait may be aided with assistant devices. Physical therapy is particularly useful for the elderly, including vestibular rehabilitation, which has been shown to decrease risk of falls. BPPV should be treated with a specific form of physical therapy called the Epley maneuver, or canalith repositioning procedure.

Vestibular rehabilitation is a useful treatment for multiple causes of vertigo, including vestibular neuritis, BPPV, and Meniere disease. It hastens recovery and improves balance, gait, and vision by increasing central compensation for vestibular dysfunction. Exercises consist of balance and gait training, as well as coordination of head and eye movements.

REFERENCES

1. Kroenke K, Lucas CA, Rosenberg ML, et al. Causes of persistent dizziness. A prospective study of 100 patients in ambulatory care. Ann Intern Med 1992;117(11):898–904.

2. Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA Jr, et al. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83(7):765–775.

|

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

According to the most recent CDC data from 2010, cough was the most frequent principal reason for ambulatory care visits, comprising over 30 million visits annually.1 For the purposes of diagnosis and treatment, cough can be easily categorized as acute (<3 weeks’ duration), subacute (3 to 8 weeks’ duration), or chronic (>8 weeks’ duration).

DIAGNOSIS

Acute Cough

Most acute cough is of viral etiology and presents as an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), viral rhinosinusitis, or acute bronchitis. Other causes of acute cough include exacerbation of preexisting conditions, such as asthma, bronchiectasis, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); occupational or environmental irritants; or serious conditions such as pneumonia, pulmonary embolus, congestive heart failure, or lung cancer.2

There are no specifically recommended tests for URTI. In patients with findings consistent with acute bronchitis, a chest x-ray may be warranted to exclude acute pneumonia if the physical exam demonstrates heart rate >100 beats per minute, respiratory rate >24 breaths per minute, oral temperature >38°C, or abnormalities on chest exam (especially in the presence of preexisting pulmonary disease, cardiac disease, or diabetes).3 Specific instances in which further diagnostic testing might be considered include:

• influenza or RSV testing if there have been suspected exposures

• pertussis testing in high-risk patients (e.g., infants, immunosuppressed, chronically ill) with suspected exposures

• chest radiography if oxygen saturation is <90%

• D dimer and, if appropriate, chest computerized tomography (CT) if there are symptoms consistent with or risk factors for pulmonary embolus (known coagulopathy or personal venous thromboembolism, family history of venous thromboembolism, recent surgery or immobilization, pregnancy or estrogen use)

Note that, in the setting of an URTI, abnormalities seen on sinus films or CT scans are often due to congestion from the infection and not diagnostic of a bacterial sinus infection.3

Subacute Cough

The differential for subacute and chronic cough often overlap. However, postinfectious cough is the most common cause of subacute cough.4 It is believed to be secondary to mucus hypersecretion and impaired clearance, but other superimposed factors, including upper airway cough syndrome and asthma, may contribute as well. Thus, if the cough has no relationship to a recent URTI or LRTI, it is reasonable to proceed with evaluation for chronic cough, as discussed below.

One should maintain a high index of suspicion for pertussis, especially if the cough is biphasic, associated with posttussive emesis, occurs in severe paroxysms, or has the characteristic inspiratory whooping sound. Laboratory confirmation can be performed via nasopharyngeal swabs for PCR, or for culture (if within 2 weeks of onset of symptoms).5

In a patient with known COPD or bronchiectasis, an acute exacerbation could persist into the subacute period. In these more complicated patients, consider chest x-ray or spirometry based on symptoms (e.g., wheezing, tachycardia, hemoptysis) and physical examination findings.

Chronic Cough

To assist in narrowing the differential for a patient with chronic cough, the clinician might proceed by first stopping any angiotension-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, encouraging smoking cessation, and confirming a normal chest x-ray. Note that the ACE inhibitor–induced cough can present from hours to months after initiation of the medication. Similarly, resolution is generally within 1 to 4 weeks of discontinuation, with literature reports of cough lingering as long as 3 months after the medication was stopped.6 In patients with a normal chest x-ray, not on an ACE inhibitor medication, the following etiologies can be considered:

• Upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) (i.e., postnasal drip, sinusitis, rhinitis). Patients with this syndrome may need to frequently clear the throat and often have nasal congestion and/or hoarseness. There may be a history of allergic or nonallergic rhinitis or sinusitis symptoms. However, there is no definitive symptom or physical finding that defines this entity. Patients may even be asymptomatic. The diagnosis is usually established by response to treatment (see below). If the patient suspected of UACS does not respond to treatment, sinus imaging may be indicated, with the understanding that positive predictive value is poor.7

• Asthma. It should be recognized that typical symptoms of asthma may not be present in patients with cough-variant asthma. When considering asthma, first do spirometry. If that is normal but the diagnosis of cough-variant asthma is still expected, definitive testing in the form of a methacholine challenge test may be explored. If this test is not easily available, empiric treatment for asthma may be tried (see below).

• Nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis (NAEB). This entity is characterized by a chronic cough, no reversible airway obstruction, a negative methacholine challenge test, and a high eosinophil count in induced sputum. Patients often have an occupational or environmental allergy that triggers the cough.8

• Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In the nonsmoker with a normal chest x-ray, who is not taking an ACE inhibitor and has not responded to empirical treatments for UACS or asthma, reflux-related cough may be considered. Patients with cough-generating GERD do not always have typical reflux symptoms. It is important to recognize that esophageal reflux may be present in patients with other concurrent causes of chronic cough; thus, a temporal association with symptoms is important. The GERD evaluation can be costly. Additionally, endoscopy and barium esophagoscopy are not useful for establishing a temporal relationship, and esophageal pH monitoring is not useful for detecting the nonacid reflux that can cause cough. Thus, more invasive diagnostic evaluation may be preceded by a medication trial, as discussed below.7,9,10

• Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). While the aforementioned etiologies ought to be addressed prior to relating a patient’s chronic cough to OSA, there have been several literature reports of higher prevalence of chronic cough in patients with OSA diagnoses, and of improved cough symptoms after CPAP treatment in patients with OSA. It has been theorized that OSA-associated GERD, UACS, and airway inflammation may be contributing mechanisms. Thus, this diagnosis ought to be considered, and completion of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and/or polysomnography may be considered in a patient with refractory chronic cough.11–13

• Tuberculosis. Although a less common etiology than those discussed above, consider tuberculosis infection in patients who are from areas with high prevalence or with risk factors (e.g., immunosuppressed or institutionalized).

• Rare causes. Sarcoidosis, congestive heart failure, pulmonary fibrosis, lung tumors, arterial venous malformations, retrotracheal masses, tracheal diverticula, trachealbronchialmalacia, chronic tonsillar enlargement, external auditory pressure (cerumen impaction, foreign body in external ear canal), and premature ventricular contractions have all been associated with chronic cough.

• Unexplained cough. If the patient continues to have cough after the above workup and/or empiric treatments for UACS and silent GERD, referral to a pulmonary or ENT specialist is reasonable. A diagnosis of habit or psychogenic cough should be made only after an extensive evaluation of other causes has been done.

TREATMENT

Empirical treatment of cough is a reasonable approach given that a few common etiologies are responsible for a great majority of cases. It has been demonstrated in the literature that the majority of chronic cough patients can be managed via primary care without intensive investigations or other referrals.10

Acute Cough

• Common cold. First-generation antihistamines (such as brompheniramine or chlorpheniramine) combined with a decongestant (pseudoephedrine) are the recommended treatment as per the 2006 ACCP guidelines. However, in a 2012 Cochrane Review of over-the-counter (OTC) medications for the treatment of acute cough in adults and children, studies assessing the efficacy of antihistamines, decongestants, antitussives, and expectorants produced conflicting results.14 The efficacy of newer nonsedating antihistamines and other OTC products has not been clearly demonstrated.3 In addition, it is difficult to determine when it is preferable to suppress cough rather than promote expectoration.2 In those unable to take an antihistamine/decongestant, intranasal ipratropium or tiotropium may be considered if there are prominent rhinitis symptoms. Short-term use of narcotic antitussives or dextromethorphan may be considered for cough suppression. If the patient is wheezing, inhaled beta-agonists may be useful.2 Use of honey for cough treatment has been studied in children, and based on a 2012 Cochrane review, honey may be slightly better than diphenhydramine in reducing cough frequency and did not differ significantly from dextromethorphan.15 Other OTC expectorants, cough syrups, drops, or antibiotics are not usually recommended.

Subacute Cough

• Postinfectious cough. If the cough interferes with the patient’s quality of life, an inhaled anticholinergic (such as ipratropium) may be helpful. If the cough persists, inhaled corticosteroids may be trialed. In some algorithms, a first-generation antihistamine with decongestant is utilized for 3 weeks when postnasal drip is thought to be contributing.14 If the patient has severe paroxysms, a 1-week course of oral prednisone may be considered, though evidence is limited.3 At this time, montelukast does not appear to be effective treatment for postinfectious cough.17,18 Additionally, long-acting beta-agonists, antihistamines, and corticosteroids have no evidence demonstrating effectiveness in pertussis infection. The effectiveness of antibiotic therapy decreases over time and is not recommended if a cough secondary to pertussis has been present more than 3 weeks. A macrolide is recommended as antibiotic treatment of choice when appropriate. Patients suspected of having acute pertussis should be isolated for 5 days from the start of treatment, and vaccination with either Tdap is crucial for controlling pertussis infection rates.3

• Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Note that this course of illness may extend from acute to chronic in nature. A short course (1 to 2 weeks) of appropriate antibiotic therapy (such as doxycycline, TMP-SMX, amoxicillin/clavulante, or macrolide) may be utilized if infection is suspected. Use maximum doses of bronchodilators (e.g., short-acting beta agonist or anticholinergic). For severe exacerbations or for those with significant underlying disease, a short course of oral corticosteroids may be necessary. A recent Cochrane review suggests that mucolytics may produce a small reduction in acute exacerbations, but appear to have little effect on quality of life.19

Chronic cough

Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians recommend empiric treatment trials addressing the following diagnoses in the order that follows, progressing to the next after treatment of the former has been ineffective.

• Upper airway cough syndrome. Intranasal corticosteroids are often effective initial therapy and can be combined with first-generation antihistamines with decongestants. Consider imaging if the above are ineffective, to exclude chronic sinusitis.3,7,20

• Cough-variant asthma. Recommended treatment is with inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators for 8 weeks. If the cough is refractory, ensure adequate inhaler technique and compliance, and consider adding an oral leukotriene receptor agonist. If that is not effective, a one-to-two-week course of oral corticosteroids may be necessary.3,7

• Nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis. First, the patient should be directed to avoid any suspected allergen or sensitizer. Inhaled corticosteroids, as for asthma, are the key anti-inflammatory therapy, and it may be reasonable to initiate treatment without induced sputum if the other diagnostic criteria are met.8

• GERD cough. Once to twice daily proton pump inhibitors for 2 months should be trialed. Recommended lifestyle changes should include tobacco cessation, less than 45 grams of fat in 24 hours, and avoidance of coffee, tea, soda, chocolate, mints, citrus, tomatoes, and alcohol. Additionally, weight loss and elevation of the head of the bed should be initiated. Prokinetic agents (such as metoclopramide) should be reserved for those with definitive diagnosis.3,9,10

It is important for the family physician to recognize the pathophysiological upregulation of the cough reflex that promotes cough hypersensitivity. There are multiple theories regarding the etiologies of this cough hypersensitivity, including a neuropathic disorder of the afferent pathways. Abnormal sensations (e.g., throat tickling or itching, choking sensation, throat clearing, hoarseness, dysphonia, dysphagia) often accompany chronic cough and may support the sensory neuropathy theory. Mechanisms of upper airway neuropathy may include GERD (repeated acid exposures), vitamin deficiencies, diabetes, and inflammation (e.g., asthma, recent viral illness) to name a few. There is literature support for use of amitriptyline and gabapentin in patients with chronic cough, especially if the efforts discussed above are not producing sufficient therapeutic result.21

SUMMARY

For patients with a chronic cough (>8 weeks’ duration) who are nonsmokers, are not taking ACE inhibitors, and have a normal chest film, the diagnosis is likely upper airway cough syndrome (UACS, formerly called postnasal drip), asthma, or GERD.

The patient suspected of having UACS should be treated empirically with intranasal corticosteroids, potentially with a first-generation antihistamine/decongestant combination.

The patient suspected of having cough-variant asthma should have spirometry and, if suggestive, be treated with a standard antiasthma regimen of inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators. If spirometry is not supportive of asthma, consider empiric treatment with inhaled corticosteroids for possible eosinophilic bronchitis.

The patient with otherwise unexplained chronic cough may have reflux disease and should be treated with lifestyle modifications and acid suppression therapy. In patients with chronic cough, recognize the potential contribution of cough hypersensitivity, and consider treatment with amitriptyline or gabapentin. For patients with chronic cough in whom the etiology is not clear, a series of empiric therapies may be tried with referrals and additional evaluation utilized as needed.

REFERENCES

1. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2010. Centers for Disease Control. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2010_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2014.

2. Dicpinigaitis PV, Colice GL, Goolsby MJ, et al. Acute cough: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Cough 2009;5:11.

3. Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough. Executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129:1S–23S.

4. Kwon N, Oh M, Min T, et al. Causes and clinical features of subacute cough. Chest 2006;129:1142–1147.

5. Madison JM, Irwin RS. Cough: a worldwide problem. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2010;43(1):1–13.

6. Dicpinigaitis PV. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough: ACCP evidence based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129(1S):169S–173S.

7. Birring S. Controversies in the evaluation and management of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:708–715.

8. Cornere M. Chronic cough: a respiratory viewpoint. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013; 21:530–534.

9. Gawron AJ, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Chronic cough: a gastroenterology perspective. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;21:523–529.

10. Ojoo JC, Everett CF, Mulrennan SA, et al. Management of patients with chronic cough using a clinical protocol: a prospective observational study. Cough 2013;9(2):1.

11. Sundar KM, Daly SE, Willis AM. A longitudinal study of CPAP therapy for patients with chronic cough and obstructive sleep apnea. Cough 2013;9(19).

12. Wang T, Lo Y, Liu W, et al. Chronic cough and obstructive sleep apnea in a sleep laboratory-based pulmonary practice. Cough 2013;9(24).

13. Faruqi S, Fahim A, Morice A. Chronic cough and obstructive sleep apnoea: reflux-associated cough hypersensitivity? Eur Resp J 2012;40(4):1049–1050.

14. Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over the counter medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings [Review]). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;15(8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree