Chapter 6 Horses, saddles and riders

The equestrian team

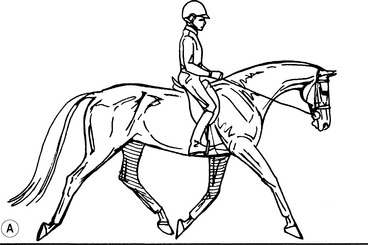

All equestrian sports reflect a partnership between horse and rider, a partnership built on communication (Fig. 6.1A). Much of this communication is conveyed through the rider’s body position (Fig. 6.2). The higher the team aims to perform, the more subtle these postural clues need to be. Hand position, tension through the reins and bit, shifts in weight along the spine and pelvis, together with a deep seat and relaxed legs, stimulate impulsion and the movement of the horse’s back. Only a relaxed rider sitting correctly can apply aids (the signals by which the rider communicates with the horse) well. An effective but soft seat is dependent on the correct position of the rider’s pelvis and spine.

Another example involves the use of aids. The intensity of a rein aid, for example, is made by slight pressure from the ring finger, by a rounding of the wrists or by using the whole arm. The intensity is sustained while increasing forward drive aids to the horse. When the horse submits, the hand relaxes and light control is maintained. An imbalance and asymmetry of the scapulae associated with pelvic malalignment will unwittingly interfere with rein tension (Figs 2.90, 2.120 C).

1. Is the horse too big or small?

2. Are their skill levels well suited?

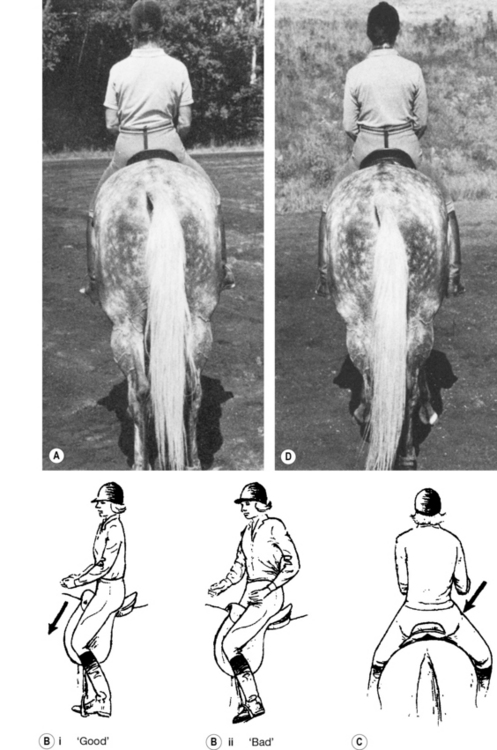

If the team is experiencing a performance issue, one first needs to determine where the problem lies. For instance, if the team veers to the left, the assessor needs to decide whether incorrect guidance from the rider is at fault, or if the problem originates from the horse. Perhaps the rider has a malalignment of the pelvis with a ‘right anterior’ innominate rotation. The right ischium will be found to be high (Figs 2.73 C, 3.86B, 6.4A,C); whereas the left ischial tuberosity is lower and puts pressure on the horse’s left paravertebral muscles, causing a reflex increase in tension in these muscles. The rider’s right shoulder and hip are too far ahead of the action, so that the rider appears to be perching on the saddle (Figs 5.37, 6.4Bii, C). The right hip ends up in extension, and the right leg goes too far behind the girth of the saddle. Incorrect signals are communicated to the horse because the sitting position of the rider is incorrect. Conversely, trapezius and paraspinal restrictions of the horse’s mid-thoracic region could shorten the left forelimb stride length, which can also result in the team veering off course. Both conditions could exist concurrently.

Malalignment in the rider

The balance and seating positions of the rider

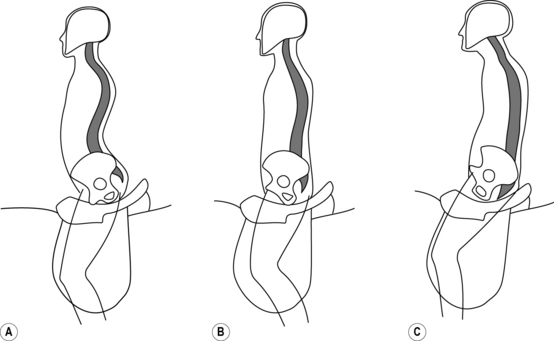

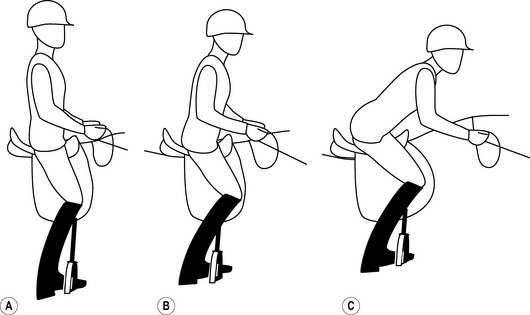

Equestrians communicate instructions to their horses through subtle changes in body and limb position. Different sports place different demands on the horse and, therefore, require a different ‘seat’ or riding position. Each seat is intended to guide and provide harmony of movement with the horse. Balance needs to remain centered, yet also needs to flow with the dynamics of the horse. In traditional English riding, there are three main seating positions in equitation (Fig. 6.3):

The dressage seat

To achieve this seat, the rider should assume a normal upper body position, with a vertical spine centered above the sacrum and the pelvis evenly positioned (Fig. 6.3A). By engaging and relaxing the paraspinal muscles, the rider is able to move harmoniously with the horse. The shoulders should be slightly retracted and depressed at the scapulae. Shoulders and heels should be in perfect vertical alignment.

The ischia and pubic symphysis form the triangle of the seat. The thighs lie flat against the saddle, with sufficient coxo-femoral internal rotation to allow the medial surface of the knee to contact the saddle fully. The line of the rider’s thigh should be as vertical as possible without taking the weight off the ischium (Figs 6.1A, 6.2B, 6.3, 6.4Bi). Having a long line to the thigh ensures a deep knee position which enables the rider to apply the lower leg to the barrel of the horse.

Should the rider be affected by a malalignment of the foot and ankle resulting in supination of the forefoot, the foot will plantarflex and elevate the heel. Consequently, weight can no longer be distributed backward through to the heel, the upper body is shifted forward and the hands drop. The head moves forward as well, into a ‘poking chin’ posture (see Fig. 6.2C).

Pelvic imbalances such as sacral torsion and/or locking of a sacroiliac joint can prevent the rider from maintaining correct positioning. For example, an ‘anterior’ rotation of the pelvis on one side, in which the innominate ends up rotated forward and upward (Figs 5.37, 6.4, 6.5), causes asymmetry in thigh position. If the rider attempts to compensate, the knee on the side of the ‘anterior’ rotation is forced either externally or internally. The former position leads to an insecure seat (Figs 5.37, 6.4Bii,C); the latter rotates the lower leg away from the horse, reducing the ability of the rider to communicate using the medial calf or heel.

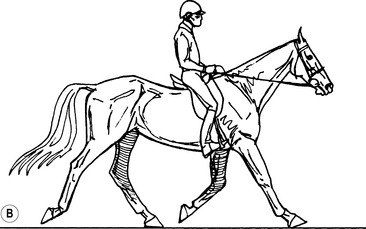

The light seat

The light seat reduces the burden of weight on the horse’s back (Fig. 6.3B). The stirrups are shortened two holes to lean the rider forward and increase flexion at the knee. This position releases some of the weight from the ischium and puts more of it through the upper leg. It also engages the hip flexors and adductors.

Pelvic malalignment results in an asymmetry of strength through the hip girdle and leg muscles (see Ch. 3, Appendix 3). This imbalance, in addition to the malpositioning of the legs, contributes to uneven weight distribution in the saddle. For the rider to achieve a true light seat, there can be no malalignment of the pelvis and spine.

The forward (jumping) seat

The forward or jumping seat is an advanced position recommended only after acquiring a safe, balanced dressage and light seat (Fig. 6.3C). It is used for both jumping and galloping and the rider must be able to transition easily between this and the light or forward seats between jumps. Failure to execute these transitions in a balanced or symmetrical fashion can throw the horse off stride.

The stirrups are again shortened to promote knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion, and are placed mid-metatarsal rather than at the metatarsophalangeal joints. Failure to position the stirrup correctly or maintain the forefoot in plantarflexion, rather than dorsiflexion, can result in ankle joint immobilization (see Ch. 3; Fig. 3.30)

Conformation of the rider

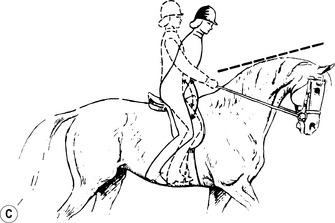

One of the most common problems to arise in training is that the horse shows signs of stiffness or a lack of willingness to laterally flex the neck and body (Fig. 6.6).The assumption is all too frequently made that this lack of willingness comes from the temperament of the horse. Changes in equipment are made, or stronger aids are used to make the horse comply.

1. When riding, is there any pain or aching between the shoulder blades (scapulae) or on one side of the neck or shoulder?

2. Has the trainer commented that, when sitting square in the saddle, the rider has:

3. Is there low back pain during or after riding?

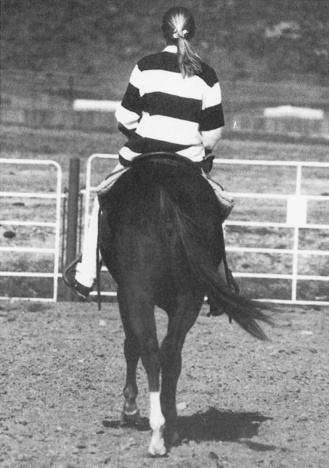

If the answer to any of these questions is ‘yes’, the rider’s weight is not distributed evenly through the saddle, resulting in an incorrect seat. ‘In balance’ in the saddle means that the pelvic (iliac) crests are even (Figs 6.4D, 2.71A,B), and that each ischium sits deeply. There is no rotation in the spine (lumbar to cervical). When the horse is working ‘in balance’, there is a rhythmic upward thrust to the pattern of movement conveyed to the rider through the horse’s back.

The rider compensates by bringing the trunk back to vertical, rotating the pelvis forward and, thereby, increasing the lumbar lordosis (Fig. 6.2A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree