Chapter 4 The malalignment syndrome

Related pain phenomena and the implications for medicine

Pain caused by an increase in soft tissue tension

Specificic sites of pain related to malalignment

Common pain syndromes caused or aggravated by malalignment

Malalignment: implications for medicine

One facet of the ‘malalignment syndrome’ seen in association with an ‘upslip’ and ‘rotational malalignment’ is the asymmetrical stress on soft tissues and joints that can eventually result in predictable sites of tenderness to palpation. With time, or as the result of a superimposed acute insult, these tender structures may become the source of overt localized and/or referred pain symptoms. The altered biomechanics also results in some commonly recognized pain patterns, injuries and ‘syndromes’ being seen with increased frequency in association with malalignment; right patello-femoral compartment syndrome is just one example (Figs 3.37, 3.38, 3.60 and see below). Unfortunately, treatment is often limited to the specific site of tenderness or pain, or to the particular pain syndrome, because of a failure to realize that these are but part of a greater entity: the ‘malalignment syndrome’. Correct the malalignment and the associated pain phenomena will often disappear spontaneously or with little additional treatment.

Pain caused by an increase in soft tissue tension

1. an increase in the length-tension ratio with any increase in the distance between the origin and insertion

2. torsion of the vertebral, pelvic or appendicular bones relative to one another

3. ‘facilitation’ and ‘inhibition’, noted to affect specific muscles in an asymmetrical pattern

4. an attempt to splint a painful or unstable area

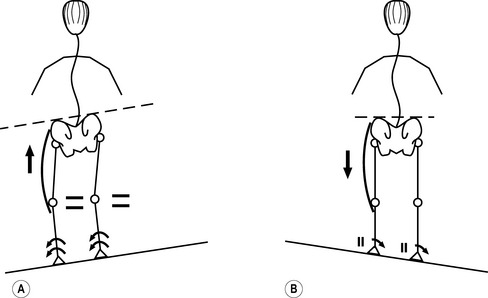

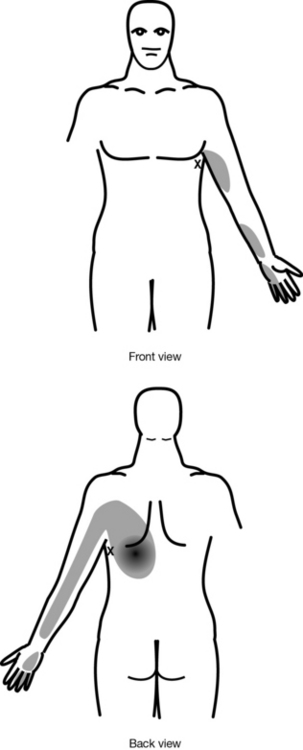

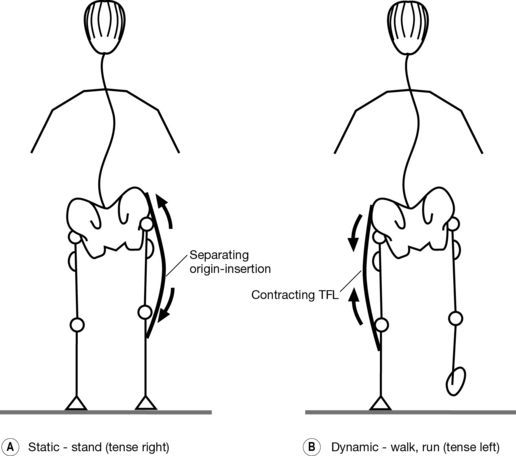

The first four mechanisms have been discussed in detail in Chapter 3 under ‘Asymmetry of muscle tension’ ( Figs 3.42–3.47). A functional LLD affects tension in both static and dynamic situations. Take the example of a person whose right side of the pelvis is higher than the left when standing. There may be an increase in tension in right hip abductor muscles and the tensor fascia lata/iliotibial band (TFL/ITB) complex because the downward drop of the pelvis on the left side increases the distance between the origin and insertion of these same structures on the right (Fig. 4.1A). When weight-bearing on the short left leg during a walk or run, the left hip abductors have to work harder to counter any drop of the pelvis on the right, perhaps even to raise the pelvis further on the right side in order to allow the long right leg to clear the ground without hindrance to swing-through (Fig. 4.1B).

Fig. 4.1 Effect of functional leg length difference (right leg long in standing) on tension in the hip abductors and tensor fascia lata/iliotibial band complex. (A) Static: in standing, tension increases on the right side as the origin and insertion are separated and muscle contraction counteracts the drop of the pelvis to the left; the person can compensate by shifting the pelvis to the right (see Figs 2.58, 3.93). (B) Dynamic: when walking or running, tension increases on left weight-bearing as the left abductors contract to counter the drop of the right side of the pelvis and to help with clearance of the ‘long’ right leg.

Box 4.1 denotes the structures that most consistently show an increase in tension and/or tenderness as a result of these various mechanisms relating to an ‘upslip’ and ‘rotational malalignment’.

Box 4.1 Structures typically showing an increase in tension and/or tenderness with ‘malalignment syndrome’

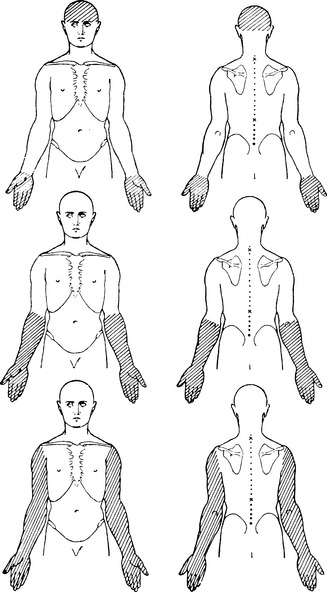

Muscles (Fig. 3.43)

1. right infraspinatus and/or teres minor

2. thoracic paravertebral muscles, especially those adjacent to sites of vertebral rotational displacement and curve reversal (e.g. the thoracolumbar junction)

3. piriformis, particularly the right one with ‘right anterior’ rotation present

4. iliopsoas, particularly the left one with ‘left posterior’ rotation present

5. the left hip abductors and TFL/ITB complex

1. a chronic increase in tension, particularly as it affects:

2. any additional increase in tension, as may occur with:

3. the tense structure being ‘strung’ over a bony or other elevation, possibly even ‘snapping’ across that prominence; e.g. the TFL over the greater trochanter and the ITB over the lateral femoral condyle (Fig. 3.41); iliacus, iliopsoas/pectineus and rectus femoris over the anterior femoral head and acetabular rim (Figs 2.46B,C, 2.59, 3.42, 4.2).

Specificic sites of pain related to malalignment

The sometimes very specific and often predictable patterns of pain and tenderness to palpation seen in association with an SI joint ‘upslip’ and ‘rotational malalignment’ are primarily the result of the four factors outlined in Box 4.2.

Box 4.2 Causes of pain on palpation seen with an ‘upslip’ and ‘rotational malalignment’

1. a chronic increase in tension in a specific soft tissue structure (e.g. joint capsule, muscle, tendon or ligament)

2. unevenly distributed or excessive pressure within and around the joints, particularly those which are weight-bearing and/or subjected to a torsional stress by malalignment (e.g. the hip and knee joints; Figs 3.37, 3.60, 3.81, 3.82, 4.3)

3. an irritation or injury of nerve roots and peripheral nerves as a result of a chronic increase in traction, compression or a combination of these (Figs 3.12, 3.13, 3.37, 3.38 and ‘Implications for neurology and neurosurgery’ below).

4. a structure that is the source of referred pain to a distant site (Figs 3.12, 3.45, 3.46, 3.62, 3.63, 3.67, 4.8–4.10)

Emotional stress

1. make the joints feel ‘stiff’

2. precipitate or worsen joint pain

3. irritate joint nerve supply to the point of hypersensitivity; presumably, there is sensitization of both the peripheral and central nervous system fibres (Butler 2000; Butler & Moseley 2003, 2007; Moseley & Hodges 2005), also impaired output of sensory signals (e.g. proprioceptive) and misinterpretation of signals which, in turn, affects motor output

Emotional complications with regards to motor output may include:

1. muscle(s) triggered too easily and/or out of sequence because of the hypersensitivity to acetylcholine (see Ch. 3 and ‘IMS’, Ch. 8); hypersensitivity of nociceptive fibres results in a more readily evoked response with any further irritation of the joint, triggering reflex muscle contraction and worsening of the joint compression – in effect, initiating and perpetuating a vicious cycle

2. inadequate contraction as sensory signals may be scattered, not arrive in unison or be weak

3. increased tendency for ‘flare-ups’, with reflex spasm triggered more readily in reaction to a pain signal

4. problems on attempting a progressive rehabilitation programme; increasing the activity level now aggravates pain and triggers ‘flare-ups’ more easily

5. initially, intermittent avoidance of activity to avert these ‘flare-ups’ and pain; eventually, persistent avoidance ‘due to their fear of reinjury or an underlying belief that they are unable to perform because of their condition [fear avoidance]’ (Vlaeyen & Linton 2000; Vlaeyen & Vancleef 2007).

Physical stress

Chronic or repetitive stress

1. increase in tension in the left complex as a result of ‘facilitation’

2. shift to left lateral weight-bearing, separating origin and insertion

3. functional weakness and tendency to fatigue more easily on this side

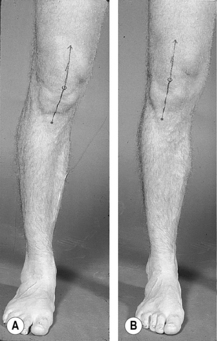

If that person now increases the number of miles walked or run on a surface with a slope banked downward to the left (e.g. running against the traffic in Canada or the USA, or with the traffic in the UK; walking clockwise on a hillside), there will be an accentuation of the left lateral shift, and the tendency toward supination and genu varum on this side (Figs 3.31, 3.36, 4.4A). The combination of increased mileage and left traction forces may, with time, make the already tender left hip abductors and TFL/ITB complex overtly symptomatic. Increasing the amount of up- and downhill running also puts more demand on this complex bilaterally; the more susceptible left complex is, however, again more likely to become symptomatic. Similarly, the left one is at increased risk with cutting actions (e.g. playing rugby, soccer or American football).

In essence, one is dealing with a type of ‘overuse’ injury. The person may get some relief on a slope banked upward to the left (Fig. 4.4B). Understandably, lateral traction forces are decreased with the left foot now on the upside and a straightening of the legs, possibly also some levelling of the pelvis which very likely is high on the right side because of the malalignment (Figs 2.72, 2.73, 2.76B). However, this practice should not be encouraged for safety reasons if it means running on a road going with the traffic.

In other words, recovery is slowed or may fail to occur until the stress caused by these forces is removed on realignment. Box 4.3 lists some ways in which the persistence of this stress could affect healing unfavourably.

Box 4.3 Negative effect of malalignment stresses on healing

1. It interferes with the flow of blood needed for:

2. Stretching a ligament results in excessive tension on nerve fibres long before the connective tissue components are affected because the nerve fibres have relatively less elasticity (Hackett 1956, 1958). The stretching can result in:

3. The stresses relating to ongoing malalignment can then perpetuate these insults:

Common pain syndromes caused or aggravated by malalignment

If we look further, we might note that this individual pronates markedly with the right foot, causing the right knee to collapse into valgus on weight-bearing; whereas the left foot pronates less so, remains in neutral or actually supinates on toe-walking or hopping. The right lower extremity is in more obvious external rotation, the left less so or even in neutral or turned inward past midline (Fig. 3.19).

By looking beyond the right knee and at the kinetic chain, we have established the reason for the pain: excessive external rotation coupled with right pronation and increased valgus stress on the right knee, with an increase of the Q-angle and lateral patellar tracking (Figs 3.37, 3.81, 4.5). The combined effect is an increase in tension in the right patellofemoral complex. Increasing the pressure with which the patella is forced onto the underlying femoral groove and condyles, and decreasing the accuracy with which the patellofemoral surfaces match up as the patella tends to track more laterally can eventually result in increased wear and tear, inflammation and pain.

1. keeping the right knee slightly flexed in an attempt to lower the pelvis on that side (Fig. 2.90)

2. secondary wasting of right vastus medialis (Figs 3.57, 3.58) that may relate to:

Malalignment: implications for medicine

The following are some examples from clinical practice that help illustrate these points.

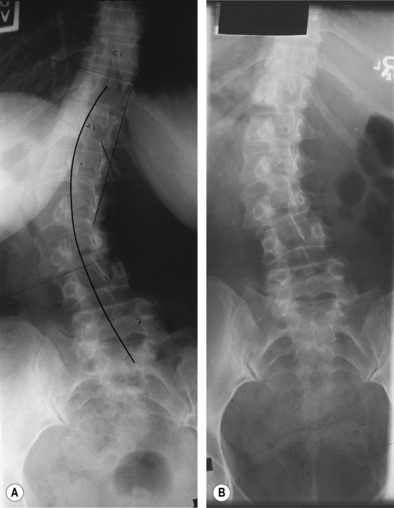

1. Some clinical presentations may be unfavourably affected by coexistent malalignment. For example, someone with idiopathic scoliosis may become symptomatic only whenever the malalignment recurs (Fig. 4.6A). These symptoms presumably result from their attempts to cope with the malalignment-related changes. In particular, there is now the pelvic obliquity and compensatory scoliosis superimposed on their underlying condition. The altered biomechanics creates additional stresses on:

2. Some of the structures that become tender and/or painful as a result of being put under increased stress, and certain of their common referral sites, are in close proximity to areas classically identified with problems in major organ systems. Both the deep iliolumbar and the anterior SI joint ligaments, for example, are capable of referring to McBurney’s point and mimicking appendicitis (Fig. 3.46).

3. Malalignment-related symptoms may mimic some common pain phenomena. Irritation of myofascial tissue at the C4-C5 level, for example, can present like a ‘carpal tunnel syndrome’ yet nerve conduction tests will prove negative and symptoms disappear with vertebral realignment (Fig. 3.12Bii). In others, increased tension with narrowing of the thoracic outlet can affect the brachial plexus to precipitate an actual carpal tunnel syndrome (Fig. 3.13).

1. some of the more common pain phenomena and syndromes that may be attributable to malalignment or can be affected by the presence of malalignment, and

2. how these conditions may overlap with problems typically dealt with by some of the medical specialties.

Implications for cardiology and cardiac rehabilitation

1. responsible for some of the more frequently encountered complaints that staff have to deal with in exercise classes on a day-to-day basis

2. one of the more common reasons for the temporary or permanent interruption of a patient’s exercise programme.

1. may not be a problem for the patient until he or she begins to exercise

2. may not be evident on initial examination but may develop with progressive increase in exercise, particularly if this now involves an asymmetric and/or torsional component

3. can result in needless investigation and ongoing patient discomfort as a result of failure to suspect malalignment in the first place.

Case History 4.1 Mrs. O.J.

1. History: two myocardial infarcts in 1994; five-vessel coronary artery bypass graft in 1995; since then, occasional angina, brought on by effort and relieved by nitroglycerine spray

2. On referral: in alignment; no musculoskeletal problems noted

3. Course: 4weeks after starting the programme, complained of interscapular pain when using the rower

4. Findings: T8 vertebral body right rotational displacement (spinous process to the left); acute pain on trunk extension, flexion and especially rotation while sitting, also with direct posteroanterior and medial pressure on the T8 spinous process

Case History 4.2 Mr. D.S.

1. History: myocardial infarct in 1997 at age 49; going on to uneventful five-vessel coronary artery bypass graft

2. On referral: no musculoskeletal complaints; malalignment of the pelvis and compensatory scoliosis but no indication of tenderness in muscles or ligaments typically put under stress

Case History 4.3 Mrs. M.M.

1. History: myocardial infarct 1995, one-vessel coronary artery bypass graft in 1996; rehabilitation programme started in August 1996

2. Discharge clinic (1997): note was made that the programme had been interrupted from Dec. 18, 1996 to Jan. 29, 1997 because of ‘low back pain’, which had persisted and was now localized to the right ‘buttock’, pointing to the lumbosacral region or nearby underlying right sacroiliac joint

3. Findings: pelvic malalignment with ‘right anterior’ rotation, also T7 rotational displacement; tenderness localizing to the left 7th costochondral junction and the ligaments crossing the posterior aspect of the right sacroiliac joint; facet stress tests negative

4. Course: realignment of the pelvis and spine resolved the low back pain and allowed return to exercising

Case History 4.4 Mrs. K.M.

1. History: pulmonary hypertension requiring the repair of an atrioseptal defect; for 3months postoperatively, ongoing tightness of the sternotomy scar area and discomfort in the left anterior chest region, leading to $30,000 of repeat investigations (including cardiac catheterization), which were all negative

2. Findings: acutely tender bilateral 4th and 5th costochondral junctions (those on the left corresponding to her site of pain); left rotation of the T6 vertebra with displacement of the 4th, 5th and 6th ribs bilaterally (similar to the T5 vertebra rotational displacement in Fig. 2.94); malalignment of the pelvis and spine

3. Course: ‘cardiac’ symptoms resolved completely on realignment combined with massage of the anterior chest and thoracic paravertebral muscles

Typical ‘cardiac’ presentations of malalignment

Back pain

Particularly important is back pain arising from the sites of stress caused by:

2. rotational displacement of any of the thoracic vertebrae, T4 and T5 being the most likely to be involved and to cause pain by stressing particularly the costovertebral and costotransverse joints at these levels (Figs 2.94A, 3.15, 3.16).

Anterior chest pain that can mimic angina

There may be anterior chest pain from the irritation of one or more of the costochondral junctions:

1. irritation of a junction caused by rib rotation or subluxation that may occur in isolation (e.g. following trauma or with a severe cough) but is also seen in association with rotational displacement of one of the thoracic vertebrae and of the attached rib or ribs (Fig. 2.94)

2. in those who have undergone open heart surgery, the vertebral rotation may itself represent a complication of the rib displacement that occurred while carrying out the sternotomy; unfortunately, the rotational displacement has persisted and now perpetuates the rib displacement and rotational stress on the costochondral junction(s), long after the sternotomy has healed.

1. the sternoclavicular joint (Fig. 2.94B)

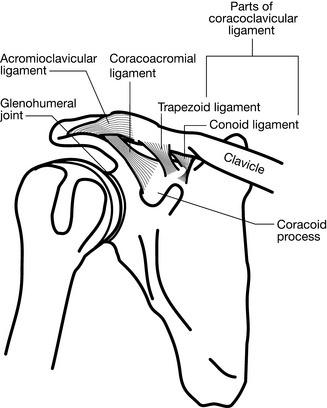

2. the acromioclavicular joint and the ligaments connecting the distal clavicle to the coracoid process, resulting in chest pain that is more anterolateral (Fig. 4.7).

Pain may radiate straight through to the anterior chest from the irritation of a disc, facet joint, costovertebral or costotransverse joint, or any other structure stressed by rotational displacement of one of the upper or mid-thoracic vertebrae; e.g. the ligaments coming off the C7 transverse process (Grieve 1986b; Fig. 3.12A,B5).

1. irritation of the roots that form the phrenic nerve (C3, C4 and C5) by rotational displacement of one of the mid-cervical vertebrae, or irritation of that nerve anywhere along its course (Fig. 3.13)

2. irritation of the autonomic nerve supply; e.g. triggering an excessive autonomic response because of irritation of the parasympathetic outflow tracts by cervical vertebral rotation or paravertebral muscle spasm

3. increased tension on the diaphragm muscle caused by:

Pain referred into one arm or to the jaw

Referral may occur from cervical spine ligaments and joints:

There may be myofascial pain and trigger points in the neck and shoulder girdle:

1. Localized pain from muscles, tendons, ligaments or fascia in this area may eventually develop with the chronic increase in tension that can result with malalignment (e.g. pectoral or intercostal muscles splinting a painful costochondral junction) and the development of trigger points within these tissues.

2. A number of the shoulder girdle soft tissues that are put under increased stress by malalignment can give rise to pain referred to the areas classically associated with angina; for example, a trigger point in latissimus dorsi can also refer along the inner arm and forearm, down to the fourth and fifth fingers (Fig. 4.8).

As part of the ‘T3’ or ‘T4 syndrome’ (see Ch. 5):

1. rotational displacement of any of the vertebrae in the T3 to T7 region but most often involving T3 or T4

2. can result in referred pain that typically involves:

Angina coexistent with symptomatic malalignment

As indicated above, the person with malalignment may present with symptoms that can mimic angina. Like the general population, 80% of those with a cardiac condition can be expected to be out of alignment (see Ch. 2). Hence, there may be those who:

1. present with an apparent cardiac problem but whose symptoms are strictly on account of a malalignment problem

2. have symptoms caused strictly by their cardiac condition, while the malalignment remains asymptomatic in terms of not causing any ‘cardiac-like’ symptoms

3. have overlapping symptoms, caused both by the cardiovascular system and the malalignment

1. they actually do suffer from ‘unstable angina’, and the recurrence of the angina at any time triggers a further increase in muscle tension that can more easily precipitate symptoms from muscles that are already tense and tender because of the malalignment

2. the angina may itself be triggered by the increase in the cardiac workload and cardiovascular changes that occur as a result of pain caused by the malalignment (e.g. secondary increase in blood pressure and heart rate)

3. the symptoms are strictly on the basis of the malalignment, and hence can also come on at rest and will fail to respond to nitroglycerine.

Dentistry

As indicated in Ch. 3, malalignment affects the joints from the toes up to the head and neck. Temporomandibular joint involvement ranges from initial minimal displacement, which can progress to subluxation and frank dislocation as the capsule and supporting ligaments are gradually stretched beyond the point of being able to provide adequate support and the muscles can no longer compensate. There results a very obvious palpable, or even visible (and sometimes, audible) displacement of the mandible on opening and closing of the jaw. Constant protective splinting, primarily of the temporal and masseter muscles, eventually results in tenderness to outright pain from that joint region which may suggest involvement of the gums and teeth.

Rotational displacement of the upper cervical vertebra, with irritation or compression of C1, C2 and C3, can cause localized pain in the base and sides of the neck and referred pain and paraesthesias in the forehead, temporal and mandibular regions (Fig. 3.12A,Bi). This pain may be hard to differentiate from the gnawing, ‘deep’ pain sometimes associated with dental problems (Blum 2004a,b).

Unilateral excessive bite, or worse still, grinding of the teeth, has been identified as either:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree