Chapter 9 Hips and Thighs

Muscles of the hip and thigh

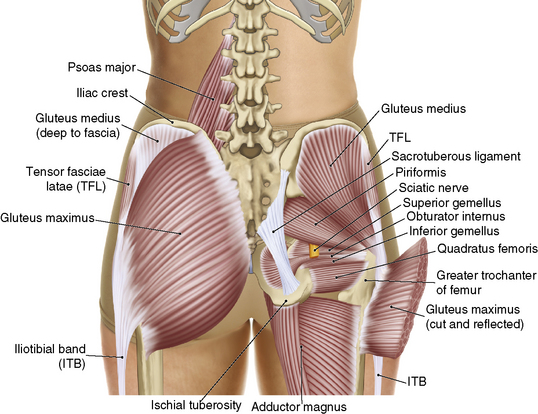

Gluteal group

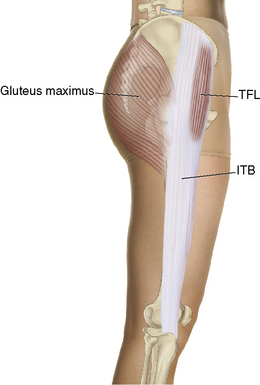

On the posterior aspect of the pelvis are the gluteal muscles. Working superficial to deep and posterior to lateral, there are three gluteal muscles: gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and the gluteus minimus. These muscles help stabilize the upper body, aid in locomotion, and extend the hip. Originating from the sacrum, the gluteus maximus is a key muscle that ties the leg to the pelvis (Figure 9-1).

Figure 9-1 Gluteal muscles.

(From Muscolino JE: The muscle and bone palpation manual with trigger points, referral patterns, and stretching, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

Although the iliotibial (IT) band or tract runs the length of the lateral thigh, we are including it as part of the hip because it acts as one of the insertion points of the gluteus maximus. The IT band also acts as an attachment site for the tensor fascia latae (TFL). The TFL is a hip abductor and has an important role as a hip stabilizer (Figure 9-2).

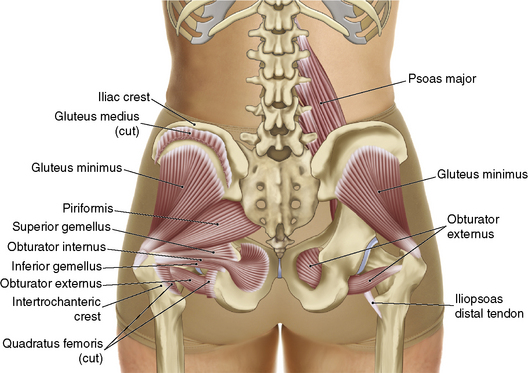

Deep lateral rotators

The deep lateral rotators, often referred to as the deep six muscles, are a group of six muscles that lie under the gluteal group. These muscles play an important role in stabilizing the pelvis and rotation of the hip. These muscles are the piriformis, gemellus superior, obturator internus, gemellus inferior, obturator externus, and quadratus femoris. This small group of muscles is a major culprit in low back and leg pain. The piriformis muscle originates from the anterior surface of the sacrum and attaches to the greater trochanter of the femur. It uses the femur as a counterbalance to maintain spinal positioning through the sacrum. Because of its positioning, the tendency to become tight and compress the sciatic nerve is common. The quadratus femoris originates from the ischial tuberosity and is often tight and tender to touch when worked (Figure 9-3).

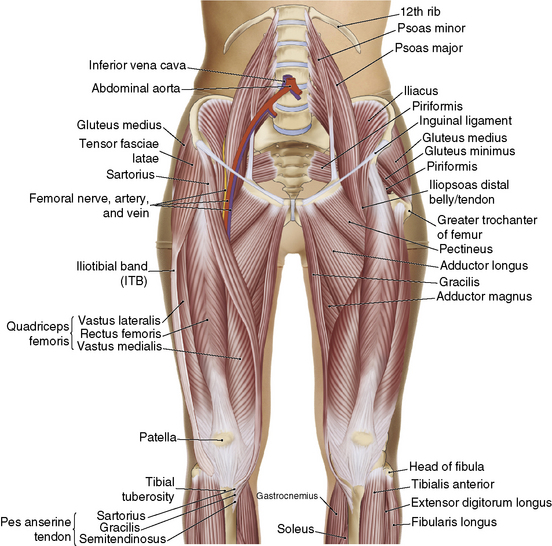

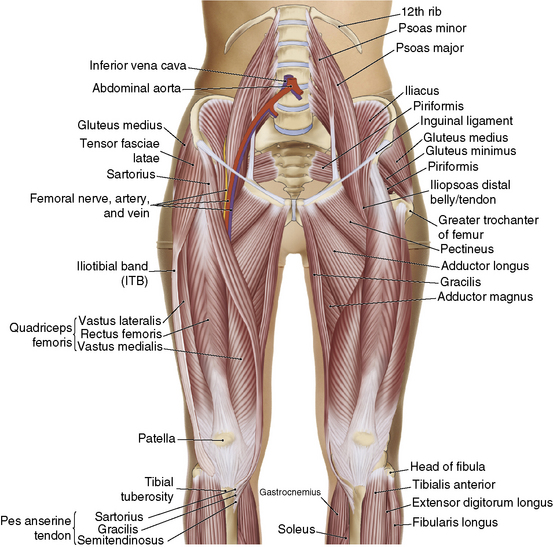

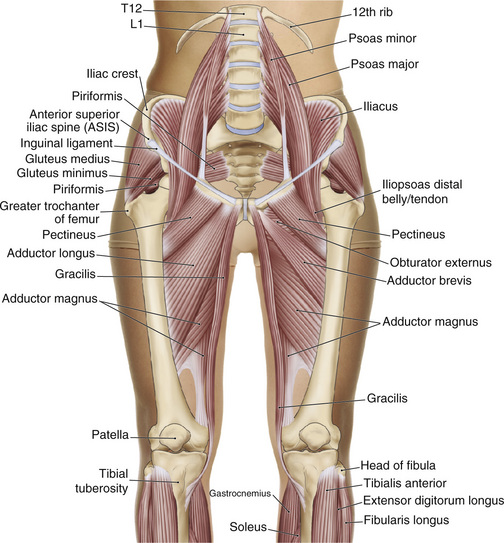

Hip flexors

The hip flexors help balance the posterior pelvic muscles. Three key muscles often become tight and shortened as a result of activities of daily living. These are the iliacus, psoas major, and the rectus femoris. The iliacus and the psoas major are often referred to as the iliopsoas because they share the same insertion at the lesser trochanter of the femur. The psoas minor inserts on the superior ramus of the pubis bone and mainly supports the natural lordotic curvature of the spine, but is only found in about 40% of the population. The psoas major originates on the anterior surface of the lumbar vertebrae and runs over the pubis bone and inserts into the lesser trochanter of the femur. This muscle not only helps to flex the hip, but also has an effect on the lordotic curvature of the lumbar vertebrae. The rectus femoris has a proximal attachment at the acetabulum and inserts into the tibial tuberosity. This long muscle plays a role in both hip flexion and leg extension (Figure 9-4).

Figure 9-4 Hip flexors.

(From Muscolino JE: The muscle and bone palpation manual with trigger points, referral patterns, and stretching, St Louis, 2009, Mosby.)

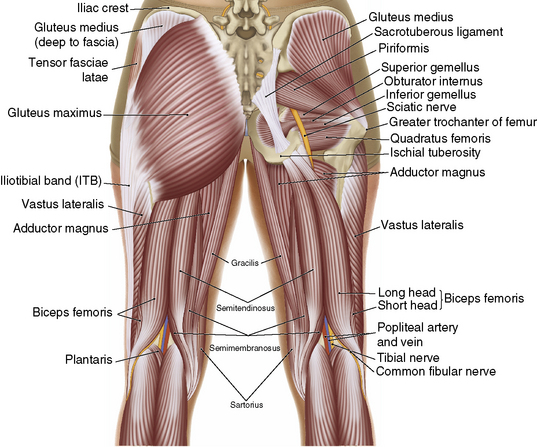

Muscles of the thigh

For the purposes of this text, when referring to the thigh we are referring to the musculature of the upper portion of the leg, between the hip and the knee. These muscles play important roles in the leg and hip positioning. Leg position and leg lengths can have a dramatic effect on the pelvic alignment, which affects the spinal alignment. An internally or externally rotated hip can have an effect not only on the pelvic position, but also on the client’s gait. A thorough assessment helps determine which muscles are tight or restricted; working from the feet up to the pelvis may help determine the focus of the session (Figure 9-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree