Hip Pain

Carol Croft

|

A 45-year-old man is seen for left hip pain that had progressed in severity for the last month. The pain especially bothers him at night making it difficult to lie on his side, which is his preferred sleeping position. On examination, he has a normal gait with full nontender, passive motion including rotation. Moderate tenderness is detected on palpation of the left greater trochanter.

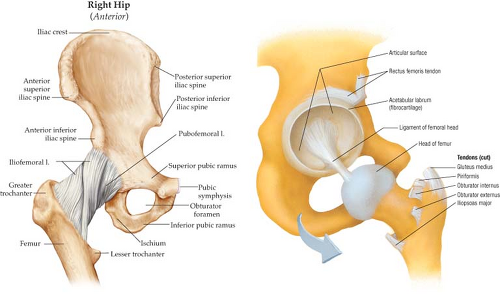

Hip pain is a common complaint in primary care and it has many possible causes. The regional anatomy of the hip and pelvis is complex, encompassing the hip and the sacroiliac (SI) joints, different groups of muscles, tendons and bursae, and the various vascular and neural structures that cross the hip joint. Referred pain can arise from the iliopsoas region, lumbosacral spine, or retroperitoneal space. Thus, the differential diagnosis is broad and includes intra-articular pathology, extra-articular pathology, and mimickers. The history and examination are critical to narrow the broad differential diagnosis.

Clinical Presentation

Patients frequently describe pain in the groin, upper thigh, or buttock as “hip” pain. Pain in the groin or medial thigh region is more often due to hip pathology and arises from irritation of the joint capsule, synovial lining, or both. Lumbosacral spine pathology can cause referred pain to the buttocks, lateral thigh, or groin. Lateral thigh pain is often attributed to trochanteric bursitis or adductor tendinitis.

Evaluation of the patient should begin with consideration of age, level and type of activity, past injuries, past surgeries, and comorbidities. Pointed questioning about childhood hip problems, such as hip dysplasia, slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), and Legg-Calve-Perthes disease is important to determine the likelihood of early degenerative arthrosis. Directed questioning should address any limitations of patient function including impairment in activities of daily living, such as donning socks, getting in and out of the car, jogging, walking, and climbing stairs. Symptoms that refer to the spine, lower abdomen, and neuropathic pain should be questioned. Comorbidities can be an important clue to the likelihood of avascular necrosis (AVN) including clotting disorders, hyperlipidemia, use of alcohol and tobacco, and previous treatment with corticosteroids. The social history including type of work and recreational exercise and exposure to altitude can also provide guidance as to the pretest probability of serious hip pathology.

Clinical Points

Correct diagnosis depends on understanding the hip anatomy.

Careful history and examination.

Cognizance of past hip pathology including developmental hip dysplasia and childhood diagnoses.

Magnetic resonance imaging is becoming the standard for evaluation of soft tissue and cartilage structures around the hip joint.

Early diagnosis of structural hip disease may prevent development of severe osteoarthritis and the need for total hip replacement.

Hip pain in children is often acute and a result of one of the three common disorders of the hip joint: acute transient synovitis, Legg-Calve-Perthes’ disease, and SCFE (1). The typical presentation of hip pain in children is

referred pain to the anterior thigh and knee joint with limping and refusing to walk. Transient synovitis is a self-limited, inflammatory condition with effusion of the hip joint. In about half the cases, a history of preceding upper respiratory infection or mild trauma can be elicited. Perthes’ disease is a result of ischemic necrosis of the femoral head that leads to collapse of the epiphysis followed by remodeling. Boys are more often affected and the age range for onset is between ages 2 and 13 years. Medical treatments include anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy (PT), and bracing to achieve optimal positioning of the femoral head in the acetabular cup. Surgery for proximal femoral osteotomy is sometimes performed. About half of untreated patients will go on to develop early onset osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip. SCFE is a disease of adolescence and is also more common in boys. It is felt to result from softening of the epiphyseal cartilage at adolescence and is more common in children with endocrinopathies, such as hypogonadism, hypopituitarism, and hypothyroidism. Surgical treatment is warranted early as only acute slipped epiphysis can be reduced, and it is usually performed bilaterally because of high risk of recurrence on the unaffected side. Congenital dysplasia of the hip joint is common and often detected with routine newborn screening. When diagnosis is delayed, limping and weakness of the surrounding muscles are the typical clinical signs. X-rays are usually diagnostic, and referral to an orthopedic surgeon for age appropriate treatments is appropriate (Fig. 7.1).

referred pain to the anterior thigh and knee joint with limping and refusing to walk. Transient synovitis is a self-limited, inflammatory condition with effusion of the hip joint. In about half the cases, a history of preceding upper respiratory infection or mild trauma can be elicited. Perthes’ disease is a result of ischemic necrosis of the femoral head that leads to collapse of the epiphysis followed by remodeling. Boys are more often affected and the age range for onset is between ages 2 and 13 years. Medical treatments include anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy (PT), and bracing to achieve optimal positioning of the femoral head in the acetabular cup. Surgery for proximal femoral osteotomy is sometimes performed. About half of untreated patients will go on to develop early onset osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip. SCFE is a disease of adolescence and is also more common in boys. It is felt to result from softening of the epiphyseal cartilage at adolescence and is more common in children with endocrinopathies, such as hypogonadism, hypopituitarism, and hypothyroidism. Surgical treatment is warranted early as only acute slipped epiphysis can be reduced, and it is usually performed bilaterally because of high risk of recurrence on the unaffected side. Congenital dysplasia of the hip joint is common and often detected with routine newborn screening. When diagnosis is delayed, limping and weakness of the surrounding muscles are the typical clinical signs. X-rays are usually diagnostic, and referral to an orthopedic surgeon for age appropriate treatments is appropriate (Fig. 7.1).

Hip pain in adolescents and young athletes may represent avulsion fractures at the site of the bony insertion of the tendons of the rectus femoris, iliopsoas, sartorius, or other regional musculature. Treatment is usually rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (Fig. 7.2).

Hip Pain in Adults

Acute hip pain located in the groin region in the setting of acute trauma in adults is most often due to fracture of the femoral head or acetabulum. Other common causes include stress fractures, AVN, muscular strain of the adductor or iliopsoas muscles and tendons, and iliopectineal bursitis. Labral tears, femoroacetabular impingement, and OA can all be signs of residual sequelae of developmental disorders of the hip joint. Inflammatory arthropathies, such as rheumatoid arthritis, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease, and septic arthritis should be entertained in the correct clinical circumstances.

The orthopedic literature has long attributed much of the OA in the hip joint to anatomical deformities. Osteoarthritis of the hip is often secondary to congenital or developmental abnormalities such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, Perthe’s disease and SCFE. Primary osteoarthritis was presumed to be idiopathic (due to developmental abnormalities of the articular cartilage), but more recent information suggest the mechanism in these cases is femoroacetabular impingement rather than excessive contact stress (2). Acetabular dysplasia is a shallowness of the acetabulum that leads to unequal distribution of stress on the acetabular cartilage, labral tears, and OA. It is often a component of developmental dysplasia of the hip, which predominantly affects women. Other anatomical abnormalities of the acetabulum such as protrusion result in overcoverage and resultant impingement between the acetabular rim and the femoral head–neck junction. Acetabular protrusion may be seen in Marfan syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis, but most cases are idiopathic.

Anatomic variations in the femur can also lead to significant abnormalities in hip joint mechanics. The most commonly recognized femoral abnormality is called “a pistol grip deformity” and is felt to be a major cause of OA of the hip in men. The deformity resembles mild SCFE and may be a developmental variant that is related. Tears of the acetabular labrum have been described in patients with developmental hip dysplasia, Perthes’ disease, previous SCFE, previous trauma, and in association with femoroacetabular impingement. Patients will generally report gradual onset of symptoms but occasionally relate the onset of pain to trauma of some kind. The pain is generally both dull and sharp groin pain and occasionally is also present in the buttock and worsened with activity or prolonged sitting (3).

Intra-articular loose bodies result from various causes including OA, AVN, pigmented villonodular synovitis, osteochondritis dissecans, and prior trauma to the hip, such as dislocation with reduction. Mechanical symptoms like clicking, locking, catching, or giving way are common along with groin pain and stiffness.

Some patients describe a popping or snapping sensation in association with pain around the hip joint. So-called “snapping hip” syndrome presents in three ways. Intra-articular snapping can result from loose bodies and labral pathology. Internal snapping is caused by the iliopsoas tendon moving over a bony prominence. Pain or discomfort associated with internal snapping indicates iliopsoas tendonitis. External snapping hip is less common and results from the iliotibial (IT) band or gluteus maximus tendon snapping over the greater trochanter. The friction of the tendon moving over surrounding bursae can result in trochanteric bursitis.

Pain overlying the trochanteric bursa is another common form of “hip pain.” The recent literature provides greater understanding of lateral hip pain or greater trochanteric pain syndrome and the contributing diagnoses. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome was originally defined as “tenderness to palpation over the greater trochanter with the patient in the side-lying position.” The typical presentation is pain and reproducible tenderness in the region of the greater trochanter, buttock, or lateral thigh. It affects between 10% and 25% of the general population. Some investigators suggest that it is more common in patients with musculoskeletal low back pain and in women compared with men.

The anatomy of the region bears review, as understanding is critical for accurate diagnosis. The greater trochanter arises from the junction of the femoral neck and shaft. Five muscles attach to it, the gluteus medium and gluteus minimus laterally and the piriformis, obturator externus, and obturator internus more medially. Superficial to the gluteus medius and minimus tendons lies a fibromuscular sheath composed of the gluteus maximus, tensor fascia lata, and IT band (Fig. 7.3) (4).

Trochanteric bursitis is a commonly diagnosed inflammatory condition with pain around the greater trochanter that radiates down the lateral thigh or into the buttock. It is believed to arise from friction created between the IT band and the greater trochanter with repeated hip flexion and extension. It can be associated with overuse, trauma, or abnormal gait patterns. Schapira et al. reported that 91.6% of patients diagnosed with trochanteric bursitis had associated pathology affecting adjacent areas, such as the ipsilateral hip or lumbar spine. Previously thought to affect primarily middle-aged women, the diagnosis is now increasing common in younger active patients of both sexes, particularly

runners. Characteristic description of the pain includes activity-related pain and symptoms lying on the affected side, as well as discomfort with prolonged standing or sitting with the affected leg crossed. The examination reveals tenderness to palpation and worsened pain on hip abduction against resistance that radiates down the lateral thigh. The FABER and Ober test are often positive as well (5).

runners. Characteristic description of the pain includes activity-related pain and symptoms lying on the affected side, as well as discomfort with prolonged standing or sitting with the affected leg crossed. The examination reveals tenderness to palpation and worsened pain on hip abduction against resistance that radiates down the lateral thigh. The FABER and Ober test are often positive as well (5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree