Hip Dislocations

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Up to 50% of patients sustain concomitant fractures elsewhere at the time of hip dislocation.

The majority of hip dislocations occur in 16- to 40-year-old males involved in motor vehicle accidents.

Almost all posterior hip dislocations result from motor vehicle accidents.

Unrestrained motor vehicle accident occupants are at a significantly higher risk for sustaining a hip dislocation than passengers wearing a restraining device.

Anterior dislocations constitute 10% to 15% of traumatic dislocations of the hip, with posterior dislocations accounting for the remaining majority.

The incidence of femoral head osteonecrosis is between 2% and 17% of patients, whereas 16% of patients develop posttraumatic arthritis.

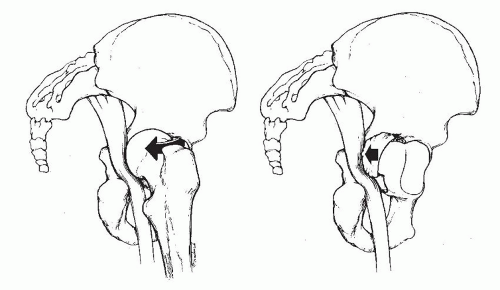

Sciatic nerve injury is present in 10% to 20% of posterior dislocations (Fig. 27.1).

ANATOMY

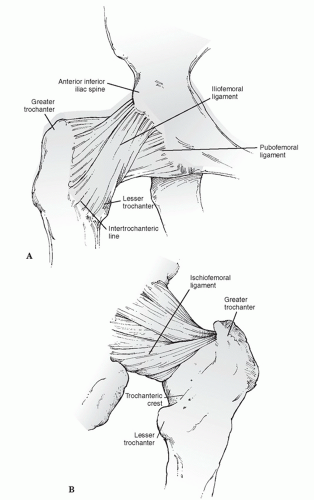

The hip articulation has a ball-and-socket configuration with stability conferred by bony and ligamentous restraints, as well as the congruity of the femoral head with the acetabulum.

The acetabulum is formed from the confluence of the ischium, ilium, and pubis at the triradiate cartilage.

Forty percent of the femoral head is covered by the bony acetabulum at any position of hip motion. The effect of the labrum is to deepen the acetabulum and increase the stability of the joint.

The hip joint capsule is formed by thick longitudinal fibers supplemented by much stronger ligamentous condensations (iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral ligaments) that run in a spiral fashion, preventing excessive hip extension (Fig. 27.2).

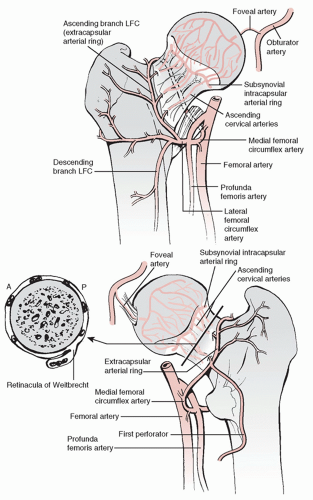

The main vascular supply to the femoral head originates from the medial and lateral femoral circumflex arteries, branches of the profunda femoral artery. An extracapsular vascular ring is formed at the base of the femoral neck with ascending cervical branches that pierce the hip joint at the level of the capsular insertion. These branches ascend along the femoral neck and enter the bone just inferior to the cartilage of the femoral head. The artery of the ligamentum teres, a branch of the obturator artery, may contribute blood supply to the epiphyseal region of the femoral head (Fig. 27.3).

The sciatic nerve exits the pelvis at the greater sciatic notch. A certain degree of variability exists in the relationship of the nerve with the piriformis muscle and short external rotators of the hip. Most frequently, the sciatic nerve exits the pelvis deep to the muscle belly of the piriformis.

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Hip dislocations almost always result from high-energy trauma, such as a motor vehicle accident, fall from a height, or an industrial accident. Force transmission to the hip joint results from one of three common sources:

The anterior surface of the flexed knee striking an object

The sole of the foot, with the ipsilateral knee extended

The greater trochanter

Less frequently, the dislocating force may be applied to the posterior pelvis with the ipsilateral foot or knee acting as the counterforce.

Direction of dislocation—anterior versus posterior—is determined by the direction of the pathologic force and the position of the lower extremity at the time of injury.

Anterior Dislocations

These injuries result from external rotation and abduction of the hip.

The degree of hip flexion determines whether a superior or inferior type of anterior hip dislocation results.

Inferior (obturator) dislocation is the result of simultaneous abduction, external rotation, and hip flexion.

Superior (iliac or pubic) dislocation is the result of simultaneous abduction, external rotation, and hip extension.

Posterior Dislocations

These comprise 85% to 90% of traumatic hip dislocations.

They result from trauma to the flexed knee (e.g., dashboard injury), with the hip in varying degrees of flexion.

If the hip is in the neutral or slightly adducted position at the time of impact, a dislocation without acetabular fracture will likely occur.

If the hip is in slight abduction, an associated fracture of the posterior-superior rim of the acetabulum usually occurs.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

A full trauma survey is essential because of the high-energy nature of these injuries. Many patients are obtunded or unconscious when they arrive in the emergency room as a result of associated injuries. Concomitant intra-abdominal, chest, and other musculoskeletal injuries, such as acetabular, pelvic, or spine fractures, are common.

Patients presenting with dislocations of the hip typically are unable to move the lower extremity and are in severe discomfort.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree