Hemivertebrae Excision

Serena S. Hu

David S. Bradford

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Congenital scoliosis can be categorized into deformities that are (a) secondary to failure of formation, (b) secondary to failure of segmentation, and (c) mixed lesions (13). Hemivertebrae are examples of failure of formation, whereas congenital bars and blocked vertebrae are examples of failure of segmentation. A unilateral unsegmented bar, especially one associated with a contralateral hemivertebra, has the worst prognosis for progression. Isolated hemivertebrae are less predictable in their growth potential, and consequently, the magnitude of the deformity that may result from continued spinal growth is uncertain. Hemivertebrae in the cervicothoracic and lumbosacral junctions are more likely to result in more noticeable deformity because of the inability of the spine above or below to compensate adequately (8). Surgery is indicated in children presenting with a significant deformity greater than 40 degrees with coronal imbalance secondary to a hemivertebra, in patients with a deformity that has shown progression on sequential radiographs, and in patients presenting with a lumbosacral hemivertebra associated with pelvic obliquity or lumbar scoliosis or both. There are several surgical options: (a) posterior spinal fusion, (b) combined anterior and posterior fusion, (c) hemiepiphysiodesis, and (d) hemivertebra excision.

Posterior spinal fusion has been reported as a gold standard in managing spinal deformity. It is a relatively straightforward procedure with minimal risks. However, in young patients with a hemivertebra, an isolated posterior fusion carries a high probability of worsening deformity because anterior vertebral growth may lead to bending and rotation of the fusion mass. A combined anterior and posterior fusion improves the fusion rate, may permit some correction if instrumentation is used and/ or a postoperative cast is added, and decreases the likelihood of bending and rotation of the fusion mass with further growth. Hemiepiphysiodesis is a useful procedure if performed in a young patient, preferably younger than 6 years, with mild-to-moderate curvatures (less than 30 to 40 degrees). However, even when convex fusion includes the involved segments of the curvature and not just the apical segments, correction of the deformity with growth is unpredictable. The early improvement may deteriorate with the adolescent growth spurt.

Excision of the hemivertebra can achieve a more reliable and greater degree of correction, as well as improvement in coronal balance. The optimal age range for hemivertebra excision is 3 to 10 years, after the growth potential of the hemivertebra has been demonstrated and before compensatory curves become structural. In older patients, a resection is still feasible even after the compensatory curves become less flexible, but the corrective surgery may require including these compensatory deformities in a more extensive fusion with instrumentation.

Hemivertebra excision is most optimally carried out at the thoracolumbar, lumbar, and lumbosacral area. Patients with hemivertebrae associated with minor curvatures (20 to 30 degrees) above the lumbosacral joint, without documentation of progression, should not be considered candidates for this procedure. Hemivertebra excision in the cervical spine poses a greater degree of difficulty and complexity and should only be performed by experienced spine surgeons. In the thoracic spine, rib resection is required and has higher risks to the spinal cord.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

A routine history and physical examination should be obtained, as would normally be done for any patient with spinal deformity. A careful examination of the spine for evidence of a hairy patch,

skin discoloration, or a sacral dimple or sinus is important. Evidence of pelvic obliquity, leg-length inequality, trunk decompensation, or neurologic dysfunction should be noted. Routine standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the spine from occiput to sacrum are necessary on all patients. At the lumbosacral junction, Ferguson views (an AP view of the L5-S1 interspace, performed by tilting the beam of the x-ray machine about 30 degrees cephalad) are often needed to better visualize the bony anatomy. Bending films are important to determine flexibility of the compensatory curvatures proximally and distally. Widening of the interpedicular distance is suggestive of intrinsic spinal cord abnormalities such as diastematomyelia. Routine myelography or computed tomography (CT) scanning is not carried out; however, CT scanning with coronal reconstructions may be useful for better defining the bony abnormalities. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine should be done in patients who have abnormal neurologic findings, in patients being prepared for operative intervention, and in patients with demonstrated widening of the interpedicular distance on routine radiographs. The MRI is important in order to rule out intracanal abnormalities such as a tethered cord, syringomyelia, diastematomyelia, or diplomyelia, or Arnold-Chiari malformation, any of which may be present in 10% to 50% of patients with congenital scoliosis (3). It is also useful in the MRI study to obtain a coronal view in the region of interest to delineate exactly where the segmentation has occurred and whether a bar exists on the contralateral side. Finally, as with other patients who have a congenital spine deformity, genitourinary abnormalities are not uncommon. Patients should be evaluated with ultrasonography or intravenous pyelography to rule out pathology. Cardiac abnormalities, although less common, may be associated as well, and any patient with a heart murmur should have an echocardiogram and/or a cardiology consultation.

skin discoloration, or a sacral dimple or sinus is important. Evidence of pelvic obliquity, leg-length inequality, trunk decompensation, or neurologic dysfunction should be noted. Routine standing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the spine from occiput to sacrum are necessary on all patients. At the lumbosacral junction, Ferguson views (an AP view of the L5-S1 interspace, performed by tilting the beam of the x-ray machine about 30 degrees cephalad) are often needed to better visualize the bony anatomy. Bending films are important to determine flexibility of the compensatory curvatures proximally and distally. Widening of the interpedicular distance is suggestive of intrinsic spinal cord abnormalities such as diastematomyelia. Routine myelography or computed tomography (CT) scanning is not carried out; however, CT scanning with coronal reconstructions may be useful for better defining the bony abnormalities. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine should be done in patients who have abnormal neurologic findings, in patients being prepared for operative intervention, and in patients with demonstrated widening of the interpedicular distance on routine radiographs. The MRI is important in order to rule out intracanal abnormalities such as a tethered cord, syringomyelia, diastematomyelia, or diplomyelia, or Arnold-Chiari malformation, any of which may be present in 10% to 50% of patients with congenital scoliosis (3). It is also useful in the MRI study to obtain a coronal view in the region of interest to delineate exactly where the segmentation has occurred and whether a bar exists on the contralateral side. Finally, as with other patients who have a congenital spine deformity, genitourinary abnormalities are not uncommon. Patients should be evaluated with ultrasonography or intravenous pyelography to rule out pathology. Cardiac abnormalities, although less common, may be associated as well, and any patient with a heart murmur should have an echocardiogram and/or a cardiology consultation.

TECHNIQUE

Hemivertebra resection can be performed via a posterior-only approach or a combined anterior and posterior approach. The posterior approach is increasingly commonly performed and is described below. The more traditional combined approach is recommended for the younger child with open growth plates, vertebra too small for posterior instrumentation, or a more tenuous spinal cord that may not tolerate even the gentle retraction that can occur with a posterior-only approach. We find that complete removal of the anterior cartilaginous growth plates is best performed by the combined anterior and posterior approach as described (2).

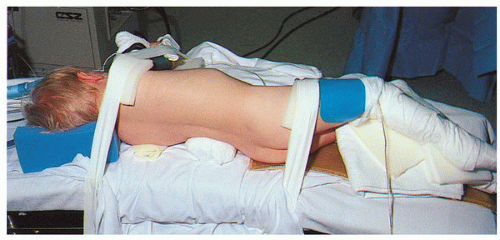

For combined anterior and posterior resection of the hemivertebra, the patient should be positioned first for the anterior resection. The patient is brought to the operating room and prepped in a routine manner. After the induction of anesthesia, a Foley catheter is inserted, and the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the convex side up. A roll may be placed under the patient at the level of the deformity to facilitate the approach (Fig. 15-1). The table is flexed to open up the level and facilitate exposure. For lumbosacral excision, the patient should be prepped and draped down to the pubis.

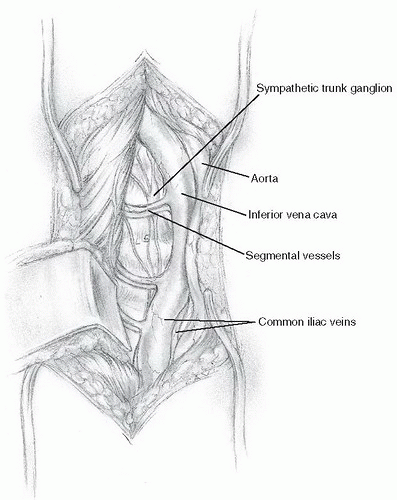

It is advisable to prep and drape from the anterior midline to the posterior midline. A standard retroperitoneal thoracoabdominal or thoracic approach is used, depending on the level of the hemivertebra. Lumbosacral lesions may be approached through a retroperitoneal incision (Fig. 15-2), whereas hemivertebra lying at the thoracolumbar junction down to L2-L3 should be approached through a thoracoabdominal approach, with removal of the 10th or 11th rib. In the thoracic spine, the rib removed is the one lying one or two levels above the hemivertebra to be excised.

FIGURE 15-1 A patient positioned in the lateral decubitus position with a roll under his waist at the level of his lumbosacral hemivertebra. |

After rib removal, it may be possible to stay extrapleural with the approach by carefully and bluntly dissecting off the pleura from the chest wall and vertebral bodies. A pediatric-sized chest retractor is used to retract the chest or abdominal wall. Once the vertebral bodies are identified (Fig. 15-3), the pleura is incised, and the segmental vessels above and below the level of the excision are carefully identified and then clipped with vascular clips or tied and divided. It is useful at this stage to take a radiograph with metal markers in both the proximal and distal disc spaces to better delineate the level and margins of the hemivertebra (Fig. 15-4).

FIGURE 15-3 The segmental vessels before ligation. The inferior vena cava and the common iliac veins are seen, and the intervertebral discs and vertebral bodies are palpable. |

The dissection of the pleura off the spine is then continued extraperiosteally to avoid excessive bleeding. Dissection must proceed around to the opposite side to allow adequate exposure and prevent damage to the arterial or venous circulation.

Excision of the hemivertebra begins with excision of the disc on each side of the hemivertebral body. The disc is first incised (Fig. 15-5) with a scalpel along with the anterior longitudinal ligament and then removed with a combination of curettes and rongeurs. The disc should be excised carefully across the vertebral interspace to the opposite concave side, with removal of the annulus and nucleus back to the posterior longitudinal ligament, along with the cartilaginous growth plates. It is desirable to leave a small portion of the annular fibers on the concave side to act as a tether, preventing translation during the second-stage posterior procedure. After the disc has been totally removed back to the posterior longitudinal ligament, the vertebral body is excised with rongeurs and curettes (Fig. 15-6). This bone is saved for later use in bone grafting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree