Hamstring Autografting/Augmentation for Lateral Ankle Instability

Alastair Younger

Heather Barske

DEFINITION

Lateral ligament instability occurs in some patients after an inversion injury.38 Although an inversion injury is common, only a few patients have ongoing ankle instability severe enough to require surgery. Persistent instability may occur in 15% to 48% of patients.7,10,15,45

Lateral ligament disruption may occur in combination with osteochondral defects, hindfoot varus, peroneal tendon tears, anterior lateral joint impingement, or a tight heel cord.29,43,48 Any of these concomitant pathologies needs to be sought during the clinical examination and treated if it represents a significant component of the ongoing symptoms.

Medial ankle instability may occur in combination with lateral ankle instability.23 In these cases, the medial ligament instability may need to be addressed at the same time.

ANATOMY

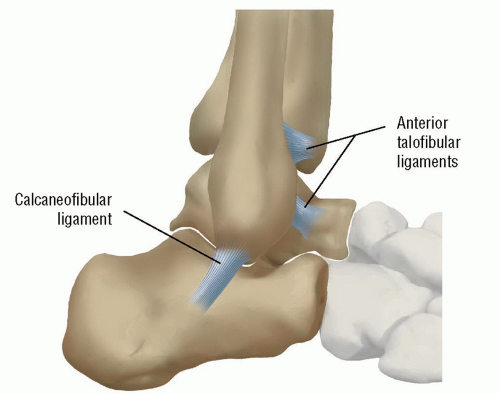

The lateral collateral ligaments include the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) and anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL).11 These are condensations within the lateral capsule.

The CFL runs from the anterior tip of the fibula to the lateral wall of the calcaneus. The ligament passes superficial to the lateral margin of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint and courses deep to the peroneal tendons to insert via a broad base onto the lateral side of the calcaneus.

The ATFL arises from the anterior portion of the distal fibula and inserts onto the lateral side of the talar neck (FIG 1).

PATHOGENESIS

Lateral ankle instability occurs after an inversion injury to the lateral ligament complex. The injury typically occurs in plantarflexion. Traditionally, the ATFL ruptures first and the CFL second.

A cavus foot may predispose the ankle to recurrent instability.

NATURAL HISTORY

Most ankle sprains resolve without the need for surgery. However, a recurrently unstable ankle treated with appropriate physical therapy protocols may benefit from lateral ankle ligament repair or reconstructions.

Left untreated, persistent lateral ankle instability may result in fixed varus tilt to the talus within the ankle mortise and eventual ankle arthritis. Most patients present because of the disability associated with the recurrent sprains.

Physiotherapy and bracing will improve symptoms in some patients with recurrent instability.

There does not appear to be a role for immediate surgery on ruptures of the lateral ligaments.26

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients should remove their socks and shoes before the history is taken so they can directly point to where the symptoms occur. Patients should be asked about pain and its relationship to activity and instability. Pointing to the foot or ankle with one finger will help focus the patient on the area of maximum discomfort and focuses the examination.

Ankle instability may be difficult for the patient to convey; it may be more subtle than recurrent inversion injuries. Patients should be asked if the ankle gives way; if possible, the position of the foot during the instability episode and circumstances (running, cutting left, cutting right, etc.) should be determined.

The impact of the instability on sports and work should be determined.

On physical examination, the patient should be examined standing and walking. He or she should be asked to heel walk and toe walk. The examiner should look for a cavus alignment to the foot. A “peek-a-boo” heel sign may assist in the diagnosis.

Using the Coleman block: If heel varus corrects, the hindfoot is considered flexible; if heel varus does not correct, the cavus deformity is secondary to a forefoot varus and correction of forefoot will correct the hindfoot through the mobile midfoot. A severe cavus deformity that is rigid may require a calcaneus osteotomy in addition to forefoot correction.

The area of maximum discomfort and instability should be elicited. We take the ankle and hindfoot through a range of motion independent of one another to determine the joint of maximum discomfort.

Peroneal tendon pathology may accompany lateral ankle instability. A resisted contraction of ankle eversion should be performed and the tendons palpated for pain and fullness (suggestive of tenosynovitis). The peroneal tendons, which are flexors, are best isolated with the ankle in plantarflexion and testing eversion against resistance. Peroneal tendon weakness accompanies most peroneal pathology due to pain; marked weakness may signify a peroneal tendon tear. In our experience, the combination of chronic ankle instability, varus hindfoot, and marked peroneal tendon weakness should raise the suspicion for a peroneal tendon tear. Occasionally, an equinus contracture may be associated with lateral ankle instability. A Silfverskiöld test (ankle dorsiflexion with the knee flexed contrasted with ankle dorsiflexion with the knee extended) allows the examiner to determine whether the contracture is isolated to the gastrocnemius or involves both the gastrocnemius and soleus components of the Achilles complex.

The ATFL resists anterior translation and medial rotation of the talus on the tibia. A direct anterior draw (pulling the talus anteriorly without plantarflexion and internal rotation) may fail to elicit instability in an unstable ankle as an intact deltoid ligament medially will prevent translation. Instead, the examiner should hold the tibia posteriorly with the left hand while translating the calcaneus anteriorly and internally rotating the foot at the same time. Side-to-side comparison to the contralateral, physiologically stable ankle assists in identifying ankle instability.

An inversion stress test determines the integrity of the CFL.

An injury to the syndesmosis (ie, “high ankle sprain”) may be elicited with a squeeze test and by rotating and translating the talus in the ankle mortise in dorsiflexion. A syndesmotic injury must be distinguished from lateral ankle instability because treatment is different.

We also routinely examine the medial ankle for deltoid instability because medial and lateral instability may coexist.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

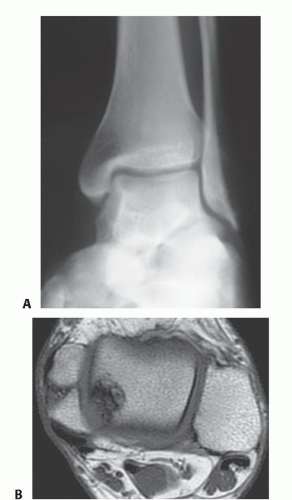

We routinely obtain weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral ankle radiographs; if more information is required, we add a mortise view. Osteochondral defects, anterior osteophytes, and tibiotalar arthritis associated with recurrent instability are generally visualized on standard radiographs of the ankle (FIG 2A).

On occasion, we add a calcaneal axial view, Saltzman view, or tibial views if we need additional information on limb alignment. Recurrent ankle instability may be secondary to tarsal coalition; if the hindfoot is stiff on clinical examination, then calcaneal axial view and standard foot radiographs may identify the coalition. Computed tomography (CT) provides greater detail of osteochondral defects, osteophytes, arthritis, and tarsal coalition and should be obtained if these associated findings are suggested on plain radiographs.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), particularly an MRI arthrogram, may provide detail of the deficient ligaments. Associated chondral and osteochondral defects as well as soft tissue impingement lesions may also be visualized by an MRI examination (FIG 2B).

Selective, diagnostic local anesthetic blocks of the ankle, subtalar, or talonavicular joints may be required to determine localized joint pain.

When the diagnosis of ankle instability is suspected but remains in question, an inversion stress test done under fluoroscopy, compared to the physiologically stable contralateral ankle, may be useful. Bone scans can assist in determining associated pathology.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Loose body in ankle

Osteochondral defect

Syndesmotic instability

Peroneal tendinopathy or rupture

Medial ankle instability

Cavus foot

Tarsal coalition

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment includes bracing and physiotherapy. Patients with recurrent ankle instability may develop peroneal tendon weakness and loss of proprioception.33,37 Physiotherapy via proprioceptive training and strengthening can resolve the ankle instability. Bracing may help a patient to recover from a sprain and prevent future

sprains by strengthening the dynamic, stabilizing peroneal tendons.

FIG 2 • A. Radiologic finding of osteochondral lesion of talar dome. B. MRI finding of osteochondral lesion of posteromedial talar dome.

Nonoperative treatment is less effective if ankle instability is associated with fixed hindfoot varus. Flexible hindfoot varus may be compensated for with a lateral wedge orthotic. If hindfoot varus is driven by a plantarflexed first ray (as determined by the Coleman block test), the orthotic should be “welled out” under the first metatarsal head, permitting further progression of the hindfoot into physiologic valgus.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The indication for surgical management of lateral ligament instability is chronic symptoms despite appropriate nonoperative management, including physiotherapy and bracing.

Surgical management of lateral ankle ligament instability includes repair (anatomic tightening of the lateral ankle ligaments) and reconstruction (reconstitution of the lateral ankle ligaments using more than the local physiologic tissue in the lateral ankle ligamentous complex).

Lateral ankle ligament reconstruction may be anatomic or nonanatomic.11 Anatomic reconstruction implies that the ligaments are rebuilt in the physiologically occurring orientation. Nonanatomic reconstruction suggests that lateral ankle support is reconstituted with tissue (typically tendon transfer to substitute for ligament deficiency) that does not follow a physiologic orientation of the ATFL and CFL.

In our opinion, the literature on this topic favors anatomic over nonanatomic reconstruction; examples of nonanatomic reconstruction include the Evans2,4,13,17,18,19,20,21,27,28,30,31,32,34,35,36,39,40,42 and Watson-Jones procedures.3,5,13,16,30,31,32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree