Hagl Lesion: Diagnosis and Repair

Curtis R. Noel

Robert H. Bell

Anterior shoulder instability, whether acute or recurrent, can be associated with numerous pathologic entities. These entities can be seen in isolation or in multiple combinations, with the most commonly encountered deficit being the detachment of the anterior glenohumeral ligamentlabral complex off the glenoid (the Perthes-Bankart lesion). Although disruption of the ligament-labral complex off the glenoid is the most common, avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament off its humeral insertion may also occur. Increasing knowledge about the mechanism of an anterior humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL), as well as advanced imaging and arthroscopic procedures, has led to better recognition and treatment of this pathologic entity. The diagnosis of a HAGL lesion requires a high index of suspicion along with the knowledge of the normal appearance of the glenohumeral ligament complex (Fig. 19.1) and the potential injury locations that may occur along its course.

The inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) functions as the primary restraint to anterior, posterior, and inferior glenohumeral translation between 45° and 90° of humeral elevation or abduction. The IGHL has a defined anterior and posterior band with an interconnecting axillary pouch or hammock that rotates with respect to arm position. Therefore, in external rotation the complex tightens anteriorly and with internal rotation it tightens posteriorly. When viewing a right shoulder glenoid en face, the anterior band of the IGHL originates between the 2 and the 4 o’clock position and the posterior band originates from the 7 to 9 o’clock position (1). The IGHL complex attaches to the humerus just below the articular surface of the humeral head. Classically, this insertion has been described in two distinct variations: a collar-like attachment and a V-shaped attachment. (2, 20).

Bigliani et al. (3) tested the failure characteristics of the IGHL-labral complex. The labrum-ligament failed at the glenoid side 40% of the time, midsubstance of the IGHL 35% of the time, and from the humeral insertion 25% of the time. Gagey et al. (4) also studied shoulder dislocations in the laboratory and found a 63% incidence of humeral-sided ligament failure. Clinically, however, the incidence of HAGL lesions after anterior dislocations ranges from only 2% to 9.3% (5, 6 and 7). To explain this disparity between the laboratory and the office, some authors have hypothesized that the dynamic shoulder stabilizers, specifically the subscapularis, protect the IGHL at its humeral insertion (8).

Nicola (1) was the first, in 1942, to identify (in four out of five surgically treated shoulder dislocations) the avulsion of the capsule from the neck of the humerus. Forty-six years later Bach et al. (9) described two more cases in which the inferior and lateral humeral insertions of the shoulder capsule were disrupted. In 1995, Wolf et al. coined the acronym HAGL for humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments. In their series of 82 patients, Wolf et al. (7) reported a 9.3% incidence of a HAGL lesion. In another large series, Bokor et al. (5) reported a HAGL incidence of 7.5% in 547 shoulders. When no Bankart lesion is identified in an anterior shoulder dislocation, the incidence of a HAGL lesion may be as high as 35% to 39% (5, 7), emphasizing the need to evaluate for HAGL lesions in shoulder injuries.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Pertinent History

The evaluation of the patient begins with obtaining the standard history and physical examination. Most patients will present with the complaint of shoulder instability after a violent traumatic event. However, there is one report of a HAGL lesion occurring after repetitive microtrauma associated with overhand throwing (10).

Physical Examination

The physical examination consists of the standard testing for shoulder instability including inspection, range of motion, strength testing, and special stability testing (apprehension test, load and shift, posterior jerk test, and inferior sulcus). Unfortunately, there is no single physical examination finding that will help differentiate a HAGL lesion from a more commonly encountered Bankart lesion and/or capsular laxity.

Imaging

Plain radiographs should be evaluated but are not often very useful in diagnosing a HAGL lesion. Occasionally, 20% of plain radiographs will reveal a bony sliver off the anterior humerus associated with a bony HAGL or BHAGL lesion (11). Otherwise, the standard shoulder radiographs should be obtained to evaluate adequate glenohumeral reduction, as well as bone loss and version on the humerus and glenoid.

A MRI study is recommended for the evaluation of the IGHL complex as well as the labrum and rotator cuff. A HAGL lesion will show up on the axial and coronal oblique images as irregularities in the humeral capsular attachment to the humerus. An MRI arthrogram will improve the specificity of the study and will demonstrate extravasation of contrast material through the region of the capsular avulsion from the humeral neck. On the sagittal oblique images, the normal axillary pouch is U-shaped, but when a HAGL is present, the axillary pouch may form a J-shape as the IGHL falls away from the humerus (11) (Fig. 19.2). In the acute setting, the increased intraarticular fluid may produce images similar to the arthrogram. Even though the MRI and MRI arthrogram are good at identifying capsular disruptions, they can miss up to 50% of the lesions (11). Once again, HAGL lesions can be associated with other pathologies (Hill-Sachs lesions, labral tear, and rotator cuff tears) and therefore, vigilance must be maintained whenever arthroscopically evaluating the glenohumeral joint.

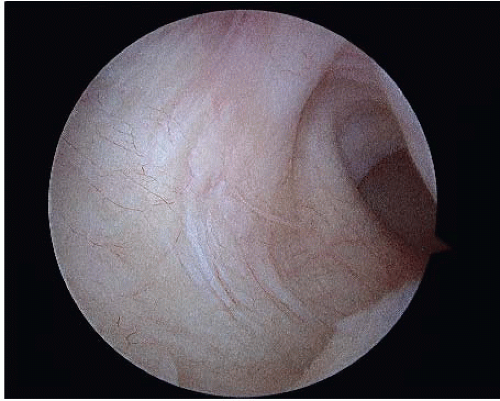

Decision-Making Algorithms and Classification

Diagnostic arthroscopy allows for the inspection of entire glenohumeral complex and its insertions on the glenoid and humerus (18). A HAGL lesion can be identified through the posterior portal with the 30° arthroscope. The lesion can be further defined with a 70° scope and/or visualizing the capsule through the anterior portal. The HAGL lesion will appear as a defect in the anterior capsule, ranging from thin attenuation of the capsular fibers to complete ligament avulsion with visualization of the subscapularis muscle fibers (Figs. 19.3 and 19.4). Internal and external rotation of the humerus will also assist in the accurate diagnosis of a HAGL lesion, allowing the humeral capsular footprint to be visualized and demonstrating the lack of capsular movement during rotation due to the loss of humeral attachment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree