HAGL: Arthroscopic/Open

James Bicos

Robert A. Arciero

INTRODUCTION

Humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL) lesions is an important but less common cause of recurrent instability in the shoulder after injury. Typically in the pathology of shoulder instability, either a capsulolabral avulsion of the anteroinferior portion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL), the so-called Bankart lesion, or capsular laxity is observed. Most literature emphasizes the importance of avulsion of the IGHL from the glenoid as the essential pathology in a traumatic dislocation of the shoulder, with the Bankart lesion accounting for 80% of posttraumatic shoulder instability (3,36).

Although reports of Bankart lesions accounting for anterior shoulder instability are seen in 45% to 100% of cases, there is evidence that the glenohumeral ligaments can fail at the humeral insertion site (17). HAGL lesions are infrequent as compared to Bankart lesions. HAGL lesions have been reported in 1% to 9% of patients with recurrent shoulder instability (5,34,37). Wolf et al. (37) looked at 64 shoulders with instability and found a 9.3% incidence of HAGL lesions. Bokor et al. (5) reviewed 547 shoulders for the cause of instability and found HAGL lesions in 7.5% of patients. They further found that in looking at their failed recurrent instability procedures, at revision surgery the incidence of a HAGL lesion was 18.2%. In another study, there was a 2% incidence of HAGL lesions in glenohumeral instability patients (7). Of those 2% of patients, 67% reported that they sustained an anterior shoulder dislocation and only 50% were detected on radiologic exam (x-ray or MRI).

In order to diagnose a HAGL lesion, one needs a high suspicion, an understanding of the anatomy of the ligaments, and its forms of injury. Approximately 66% of HAGL lesions in the literature had other associated abnormalities at the time of arthroscopy (6). Failure to diagnose the HAGL lesion could lead to persistent instability and pain. More commonly, HAGL lesions have been associated with rotator cuff tears, Bankart lesions (i.e., a floating IGHL), Hill-Sachs lesions, and labral tears (7). Because of the associated pathology with HAGL lesions, a thorough arthroscopic inspection of the shoulder should include the axillary pouch and the IGHL attachment to the humeral neck to avoid missing the lesions (2,13). Bach et al. (2) state that in the absence of capsular laxity and glenoid pathology, a disruption of the lateral capsule (i.e., HAGL lesion) must be excluded.

ANATOMY

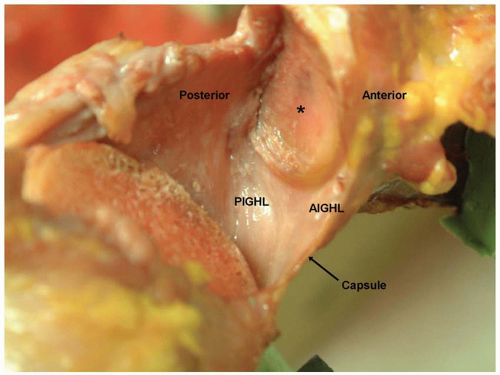

A complete review of the anatomy of the shoulder is beyond the scope of this chapter. The main focus is on the IGHL complex. The IGHL has two bands, the anterior inferior glenohumeral ligament (AIGHL) and the posterior inferior glenohumeral ligament (PIGHL). The IGHL also has an axillary pouch that spans between the AIGHL and the PIGHL (23) (Fig. 11.1)

In the right shoulder, the AIGHL extends from the 2:00 to 4:00 position and the PIGHL extends from the 7:00 to 9:00 position. The IGHL complex attaches to the medial humerus just under the cartilage of the humeral head. Two configurations have been identified. One is a collar-like attachment where the entire IGHL complex inserts just below the anatomical neck of the humerus. The other is a V-shaped attachment, where the AIGHL and PIGHL attach at the margins of the humeral neck cartilage surface and the interposing pouch inserts more distal on the neck of the humerus (2,23).

Numerous studies have shown the functional importance of the IGHL in maintaining shoulder stability with range of motion (23,35). The IGHL is the primary restraint to anterior shoulder dislocation with the arm at

90 degrees of abduction and external rotation (35). Other stabilizing structures include the labrum as a static stabilizer and the subscapularis muscle as a dynamic stabilizer with the arm at zero degrees of abduction (37).

90 degrees of abduction and external rotation (35). Other stabilizing structures include the labrum as a static stabilizer and the subscapularis muscle as a dynamic stabilizer with the arm at zero degrees of abduction (37).

ETIOLOGY

Nicola has been credited with describing the first known HAGL defect after an anterior shoulder dislocation (22). He reported on four of five acute cases of shoulder dislocations producing HAGL lesions and found HAGL lesions in 6 of 25 recurrent shoulder dislocations. He followed up the study with a cadaver study on 50 shoulders where he reproduced an anterior shoulder dislocation. The results showed that unlike a Bankart defect that occurs with the arm in an hyperabducted position with impaction, the HAGL lesion was most likely to occur with the arm both in the hyperabducted and externally rotated position (5,22).

Fourteen percent of HAGL lesions reported in the literature occurred in shoulders with prior surgeries. The data are unable to support if the prior surgeries placed the patients at an increased risk for future shoulder injury (7). Shoulder dislocations are associated with different structural abnormalities, depending on the age of the patient. Younger patients are more likely to disrupt the anterior labral-ligamentous attachment to the glenoid. Older patients are more likely to disrupt the anterior capsular attachment to the humerus (HAGL lesion) and also may disrupt the subscapularis tendon. In fact, older patients with anterior dislocations may be misdiagnosed with an axillary nerve neuropraxia or a rotator cuff tear if they cannot abduct their arm (20,21). The difference in pathology due to age may be secondary to a weakening of the rotator cuff and weakening of the capsular attachment to the humerus. This results in a higher likelihood that the capsular humeral interface fails rather than the capsular-glenoid interface (18,20). In patients who sustained a documented first-time anterior shoulder dislocation, 33% developed shoulder instability secondary to a HAGL lesion (20).

The reported incidence of HAGL lesions has increased with shoulder arthroscopy. Therefore, it could be a site for ligament failure more commonly than previously believed (5,13). Trauma has been shown to contribute to HAGL lesions in over 94% of reported cases in the literature (12,29), but there has been one reported case of a HAGL lesion after a repetitive microtrauma from overhead throwing (15). Warner first described a combined Bankart and HAGL lesion, the so-called floating AIGHL. He treated it with an open repair and had excellent results (36).

CLASSIFICATION

There are three possible locations of injury to the IGHL—failure at the glenoid, failure at the humerus, or an intrasubstance tear. In addition, one could have an injury to the AIGHL or PIGHL in each of the locations described above. Lastly, when the failure occurs at the humerus, it could either be a pure ligamentous tear or a piece of the medial cortex of the humerus could avulse off with the ligament producing a bony HAGL (BHAGL).

Bigliani et al. (4) in a biomechanical study evaluated the tensile property of the IGHL bone-ligament-bone complex. His results showed IGHL failure at the glenoid in 40% of cases, an intrasubstance tear in 35% of cases, and a HAGL lesion in 25% of cases. Another cadaveric study by Gagey et al. (14) showed a HAGL lesion in 63% of specimens tested for dislocations. They speculated that the higher rate of HAGL lesions in cadavers than in human subjects was the due to the loss of the protective role of the subscapularis muscle in cadaver specimen testing. A much later study by the same author showed that when a HAGL lesion does occur, there needs to be a significant avulsion of that ligament from the humerus before the shoulder would dislocate. Smaller ligament avulsions did not produce shoulder dislocations (26).

TABLE 11.1 Frequency of HAGL LesIons Based on Anatomic Location | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

A posterior HAGL lesion (PHAGL) has been recognized as a cause of shoulder pain, posterior instability, and discomfort (8,10,30). PHAGL lesions have been associated with other shoulder abnormalities in 67% of cases (17).

In order to try and standardize the nomenclature for tears of the IGHL complex, Bui-Mansfield et al. (6) proposed a classification scheme derived from the terminology in the literature combined with the anatomic sites of rupture of the IGHL. They found six different forms of HAGL lesions based on the involvement of the anterior or posterior band of the IGHL, the presence or absence of a bony avulsion, and whether or not a labral tear was also identified in the injury pattern. The anterior band was involved in 97% of the HAGL lesions. The strict avulsion of the IGHL from the humerus could either be purely ligamentous—anterior HAGL (AHAGL); or with a bony lesion—BHAGL. The last option is a floating HAGL where both the humeral and the glenoid sides of the IGHL complex are torn. The same nomenclature exists for the PIGHL. Table 11.1 lists the frequency of HAGL lesions based on their anatomic locations. In other literature, the frequency of HAGL as compared to a floating AIGHL, and a BHAGL is 59%, 22%, and 20%, respectively (2,5,13,24,31,36,37).

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

Although no specific historical feature will indicate the presence of a HAGL lesion, the senior author has observed a higher preponderance of this lesion in wrestlers. In this mechanism, the wrestler almost always reports a combination of hyperabduction and external rotation. No specific clinical test can specifically differentiate a HAGL lesion from a Bankart lesion (25). In addition, the review of a complete shoulder examination is beyond the scope of this chapter, but there are some clinical examinations that should be mentioned.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree