Chapter 67 Gout and Other Crystalline Arthropathies

Crystalline Arthropathies

Gout

Gout, first described in antiquity by Hippocrates, is becoming increasingly prevalent,10 yet remains underdiagnosed and poorly managed in the clinic.

Gout is an end result of sodium urate crystal deposition in joints and soft tissues as a consequence of chronic hyperuricemia. Uric acid is produced via the metabolism of purines. The breakdown of guanine and adenine converges at an intermediate product, xanthine, which is then converted to uric acid via xanthine oxidase. In most mammals, the enzyme uricase then breaks uric acid down to allantoin, a highly soluble, easily excreted molecule. However, humans, great apes, and some New World monkeys developed mutations in the uricase gene approximately 8 to 24 million years ago, leading to gene silencing.21 The result has been an inactive uricase, the accumulation of uric acid, and serum urate levels higher than those seen in other mammals.19 Although much of the uric acid is excreted by the gut, a significant portion is renally excreted; accordingly, any failure of renal urate excretion may result in absolute hyperuricemia.17

Uric acid is soluble in serum up to a concentration of approximately 6.8 mg/dL, above which deposition of urate crystals can occur. Peripheral joints are typically the sites of urate deposition because of the effects of temperature on crystal solubility—namely, at lower temperatures (e.g., in the peripheral joints, which are several degrees cooler than core body temperature), urate crystals are less soluble in serum and precipitate out of solution into joints and soft tissues. Other factors promoting crystal formation in joints, such as differences in synovial fluid protein concentrations, may also play a role. Although serum uric acid concentrations greater than 6.8 to 7.0 mg/dL predispose to developing gout,8 only a minority of patients with elevated uric acid levels actually go on to frank gout, and the diagnosis of gout should never be made on the basis of elevated serum uric acid levels alone. The higher the serum uric acid level, however, the more likely a given patient will be suffering, or will eventually go on to suffer, gouty arthropathy.

Most patients suffering their first gouty attack are men between the ages 30 to 60 years. Male sex hormones may contribute to rising uric acid levels (by reducing uric acid renal excretion), and therefore gout in males is typically delayed, at least until after puberty. Conversely, estrogen is uricosuric (i.e., helps maintain low serum urate levels),16 so women rarely have hyperuricemia or gout before menopause. Aside from androgens and estrogen, other factors influencing serum uric acid concentration include diet and renal function. As expected, a diet rich in purines increases the risk of gout. Purine-rich foods include oily fish (e.g., sardines, herring, mackerel), shellfish, beer, and organ meats such as sweet bread and liver. Although many of these foods are also high in protein, protein consumption per se does not increase serum urate levels and may actually stimulate renal urate excretion. Alcohol consumption also raises serum urate levels and some alcoholic beverages (e.g., beer, ale) are simultaneously high in purines. Often, patients with gout present with an acute arthritic attack shortly after ingestion of a large purine load (e.g., heavy beer consumption, shrimp), which leads to a sudden and precipitous rise in serum uric acid levels. Some investigators have suggested that excessive consumption of fructose, a common food additive, also contributes to hyperuricemia.5 Urate clearance declines with kidney function, so that patients with impaired renal function have elevated serum uric acid levels and a higher incidence of gout. Some medications block urate excretion, such as thiazide diuretics used for hypertension. Probably because a number of these secondary risk factors for hyperuricemia are increasing, the prevalence of gout has increased by as much as fourfold in the past few decades.4

Acute Gout: Presentation and Evaluation

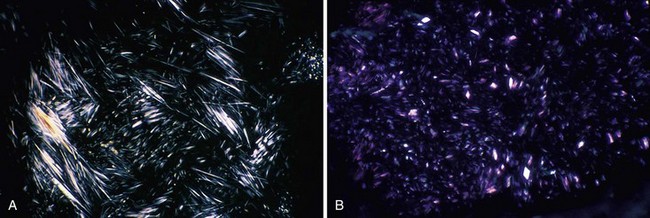

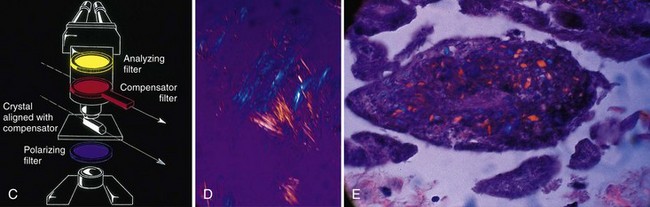

On examination, the involved joint(s) is generally warm, red, swollen, and markedly tender. Loss of motion because of pain and swelling is the norm. Signs of systemic inflammation may be present, including fever and tachycardia. Joint effusions are usually noted with knee involvement and, if the diagnosis has not already been definitively been made, fluid should be withdrawn not only for therapy, but also for cell count, which in gout will be inflammatory and neutrophil-predominant, crystal identification, and Gram stain and culture. The key to diagnosis is the identification of urate crystals under a polarizing microscope (Table 67-1). Urate crystals are negatively birefringent, so the needle-shaped crystals should appear yellow when viewed parallel to the optical axis and blue when perpendicular (Fig. 67-1). Extracellular urate crystals confirm that the patient has gout, but may persist in the joint long after prior attacks; consequently, only intracellular crystals in neutrophils unequivocally confirm that the patient is in the midst of a gouty attack (i.e., that the crystals are activating neutrophils).

Table 67-1 Common Crystal-Associated Arthropathies

| Parameter | Gout | Pseudogout |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal | Sodium urate | Calcium pyrophosphate |

| Radiograph | Early: Soft tissue swelling Later: Radiolucent erosions around edge of articular cartilage | Fine, radiopaque, linear deposits in the menisci and articular cartilage |

| Frequency of occurrence in knee | Common | Very common; increases with age, DJD |

| Laboratory studies | Elevated serum uric acid | None |

| Crystal shape | Needle-shaped | Rhomboid |

| Crystal character with compensated polarized light | Parallel, yellow; perpendicular, blue (negatively birefringent) | Parallel, blue; perpendicular, yellow (positively birefringent) |

DJD, Degenerative joint disease.

From Vigorita VJ: The synovium. In Vigorita VJ, Ghelman B (eds): Orthopaedic pathology, Philadelphia, 1999, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, p 596.

Chronic Gout

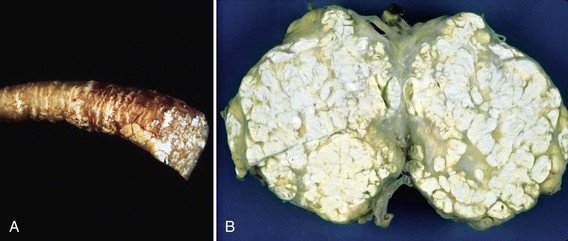

Patients whose gout has persisted for many years, typically with excessive hyperuricemia and multiple episodic acute attacks annually, may proceed to a more chronic phase characterized not only by continued episodic attacks, but by a persistent, smoldering inflammatory arthritis in the affected joints. In addition, such individuals may go on to develop tophi (Latin for “stone”)—the deposition of crystal aggregates, many large and surrounded by a corona of inflammatory cells. These tophi are most visible in soft tissue areas such as the olecranon bursa but may be present in almost any tissue (Fig. 67-2). In the bone and cartilage, they may invade and contribute to joint destruction. On plain x-ray, patients with chronic tophaceous gout may have typical erosive changes, particularly of the feet and hands (see Table 67-1). These distinctive erosive changes appear as punched-out lesions, with overhanging edges of bony cortex, and are diagnostic.20

Diagnosing Gout

Diagnosing gout can be straightforward, but a few caveats deserve mention. Although an acute gouty attack involving the first MTP joint is typical enough to merit its own name, podagra, acute gouty arthritis can presents in a multitude of ways. In men, initial attacks can occur in the ankles, knees, olecranon bursae, hands, or soft tissue of the feet—almost anywhere—and can be mono- or polyarticular. Polyarticular gout attacks become more common as the disease progresses. As noted earlier, women rarely develop the disease until several years after menopause, and women do not typically experience podagra. In contrast to men, women may more commonly experience initial and/or subsequent attacks in the upper extremities and, in particular, in small joints affected by osteoarthritis, because urate crystals have a predilection to deposit in previously damaged joints.6 Older women with gout not uncommonly have tophaceous deposits in osteoarthritic nodes in their distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, and an examiner should look for chalky white subcutaneous deposits in the DIP joints in this patient population.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree