Glenohumeral Dislocation

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The shoulder is the most commonly dislocated major joint of the body, accounting for up to 45% of dislocations.

Anterior dislocations account for 96% of cases. Posterior dislocations, the second most common direction of dislocation, account for 2% to 4% of cases.

Inferior (luxatio erecta) and superior shoulder dislocations are rare, accounting for approximately 0.5% of cases.

The incidence of glenohumeral dislocation is 17 per 100,000 population per year.

Incidence peaks for males in the 21 to 30 year age range and for women in the 61 to 80 year age range.

Recurrence rate in all ages is 50% but rises to almost 89% in the 14 to 20 year age group.

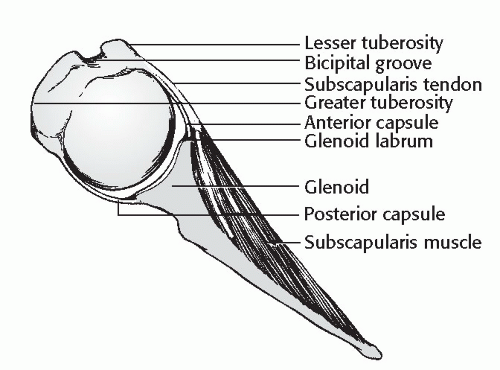

ANATOMY (FIG. 14.1)

Glenohumeral stability depends on both passive and active mechanisms, including:

Passive:

1. Joint conformity.

2. Vacuum effect of limited joint volume.

3. Adhesion and cohesion owing to the presence of synovial fluid. 4. Scapular inclination: for >90% of shoulders, the critical angle of scapular inclination is between 0 and 30 degrees, below which the glenohumeral joint is considered unstable and prone to inferior dislocation.

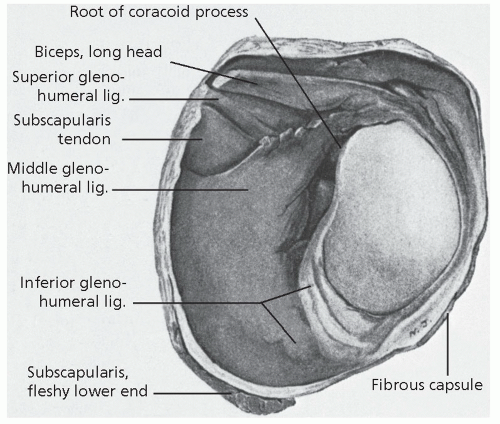

5. Ligamentous and capsular restraints (Fig. 14.2).

Joint capsule: Redundancy prevents significant restraint, except at terminal ranges of motion. The anteroinferior capsule limits anterior subluxation of the abducted shoulder. The posterior capsule and teres minor limit internal rotation.

The anterior capsule and lower subscapularis restrain abduction and external rotation.

Superior glenohumeral ligament: This is the primary restraint to inferior translation of the adducted shoulder.

Middle glenohumeral ligament: This is variable, poorly defined, or absent in 30%. It limits external rotation at 45 degrees of abduction.

Inferior glenohumeral ligament: This consists of three bands, the superior of which is of primary importance to prevent anterior dislocation of the shoulder. It limits external rotation at 45 to 90 degrees of abduction.

Coracohumeral ligament: This is a secondary stabilizer to inferior translation.

6. Glenoid labrum.

7. Bony restraints: acromion, coracoid, glenoid fossa.

Active:

1. Biceps, long-head

2. Rotator cuff

3. Scapular stabilizing muscles

Coordinated shoulder motion involves:

1. Glenohumeral motion

2. Scapulothoracic motion

3. Clavicular and sternoclavicular motion

4. Acromioclavicular motion

Pathoanatomy of shoulder dislocations:

This involves a stretching or tearing of the capsule, usually off the glenoid, but occasionally off the humerus due to avulsion of the glenohumeral ligaments (HAGL lesion).

Labral damage: A “Bankart” lesion refers to avulsion of anteroinferior labrum off the glenoid rim. It may be associated with a glenoid rim fracture (“bony Bankart”). This is found in 40% of shoulders undergoing surgical intervention.

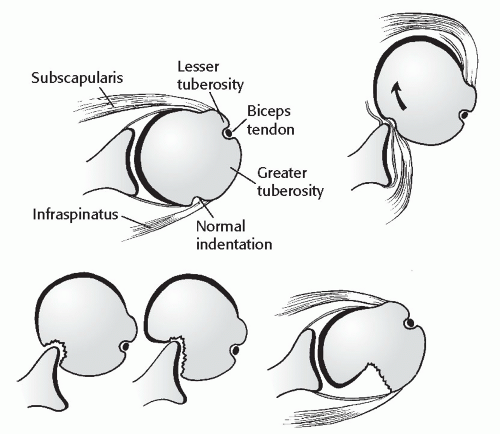

Hill-Sachs lesion: A posterolateral head defect is caused by an impression fracture on the glenoid rim; this is seen in 27% of acute anterior dislocations and 74% of recurrent anterior dislocations (Fig. 14.3).

Shoulder dislocation with associated rotator cuff tear.

Common in older individuals.

>40 years old: 35% to 40%

Ultrasound may be considered in patients >40 years old with a first-time dislocation.

>60 years old: may be as high as 80%

Beware of an inability to lift the arm in an older patient following a dislocation.

ANTERIOR GLENOHUMERAL DISLOCATION

Incidence

Anterior dislocations represent 96% of shoulder dislocations.

Mechanism of Injury

Anterior glenohumeral dislocation may occur as a result of trauma, secondary to either direct or indirect forces.

Indirect trauma to the upper extremity with the shoulder in abduction, extension, and external rotation is the most common mechanism.

Direct, anteriorly directed impact to the posterior shoulder may produce an anterior dislocation.

Convulsive mechanisms and electrical shock typically produce posterior shoulder dislocations, but they may also result in an anterior dislocation.

Recurrent instability related to congenital or acquired laxity or volitional mechanisms may result in anterior dislocation with minimal trauma.

Clinical Evaluation

It is helpful to determine the nature of the trauma, the chronicity of the dislocation, pattern of recurrence with inciting events, and the presence of laxity or a history of instability in the contralateral shoulder.

The patient typically presents with the injured shoulder held in slight abduction and external rotation. The acutely dislocated shoulder is painful, with muscular spasm.

Examination typically reveals squaring of the shoulder owing to a relative prominence of the acromion, a relative hollow beneath the acromion posteriorly and a palpable mass anteriorly.

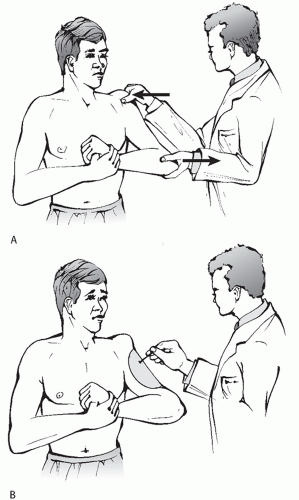

A careful neurovascular examination is important, with attention to axillary nerve integrity. Deltoid muscle testing is usually not possible, but sensation over the deltoid may be assessed. Deltoid atony may be present and should not be confused with axillary nerve injury.

Musculocutaneous nerve integrity can be assessed by the presence of sensation on the anterolateral forearm (Fig. 14.4).

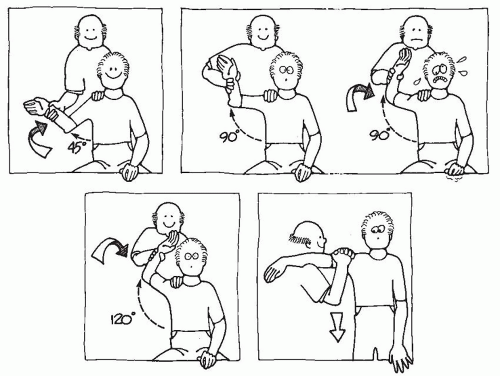

Patients may present after spontaneous reduction or reduction in the field. If the patient is not in acute pain, examination may reveal a positive apprehension test, in which passive placement of the shoulder in the provocative position (abduction, extension, and external rotation) reproduces the patient’s sense of instability and pain (Fig. 14.5).

Radiographic Evaluation

Trauma series of the affected shoulder: Anteroposterior (AP), scapular-Y, and axillary views taken in the plane of the scapula (Figs. 14.6 and 14.7).

Prereduction radiographs should be considered in all first-time dislocations, patients over age 40 years, and following high-energy trauma as these patients have a higher risk of associated fracture.

Velpeau axillary: If a standard axillary cannot be obtained because of pain, the patient may be left in a sling and leaned obliquely backward 45 degrees over the cassette. The beam is directed caudally, orthogonal to the cassette, resulting in an axillary view with magnification (Fig. 14.8).

Special views:

West Point axillary: This is taken with patient prone with the beam directed cephalad to the axilla 25 degrees from the horizontal and

25 degrees medial. It provides a tangential view of the anteroinferior glenoid rim (Fig. 14.9).

Hill-Sachs view: This AP radiograph is taken with the shoulder in maximal internal rotation to visualize a posterolateral defect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree