Giant Cell Arteritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Angelo Gaffo

|

A 76-year-old white woman presents to her primary care physician with a 3-month history of progressive fatigue, malaise, poor appetite, and a 10-lb weight loss. She also reports bilateral shoulder and hand pain. No visual complaints are reported, and on examination, she is noticed to have mild bilateral metacarpophalangeal swelling and pain with palpation. Laboratory findings include a normochromic, normocytic anemia (hematocrit of 28%) and increased inflammatory markers with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 60 mm/hour. No erosions are noted on hand radiographs, and a tentative diagnosis of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis is made. While the patient waits for a rheumatology referral she is placed on a 10-mg dose of oral prednisone.

Two weeks later when she is seen by a rheumatologist, the fatigue, malaise, poor appetite, and arthritis are mildly improved, but still present. No visual complaints are reported, but the patient has developed persistent jaw discomfort and weakness while chewing as well as headaches, with scalp tenderness noted while laying on a pillow or wearing glasses. On physical examination there is a palpable temporal artery (Fig. 15.1) and significant scalp tenderness. Additional findings include continued shoulder and pelvic girdle pain on palpation. Laboratory findings are largely unchanged, with an ESR at 56 mm/hour.

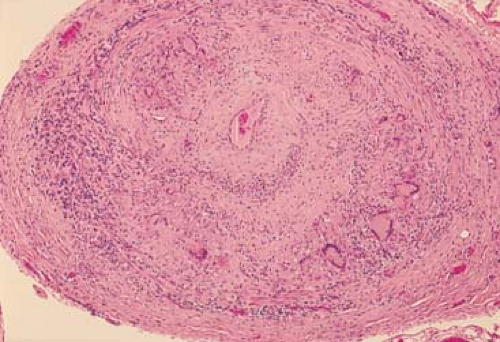

A temporal artery biopsy is scheduled in the next days and is shown in Figure 15.2.

Clinical Presentation

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and giant cell arteritis (GCA) are two clinical conditions that share multiple pathophysiologic and clinical characteristics. Both almost exclusively affect individuals older than 50 years, are characterized by musculoskeletal pain and stiffness, and are usually accompanied by prominent constitutional symptoms such as malaise, weight loss, and elevated inflammatory markers. In addition, both the diseases have a good response to different dosages of glucocorticoid therapy. Whereas PMR limits its involvement to the musculoskeletal system, GCA is a pan-arteritis that affects the aorta and its main branches with a special, but not exclusive, predilection for the extracranial branches of the carotid artery. As a consequence, early recognition of GCA is essential to avoid its more feared ischemic consequences, including irreversible vision loss. Polymyalgia rheumatica can evolve into GCA, with this clinical continuum leading many authors to consider PMR a forme fruste of GCA in which overt vasculitis has not developed.

Both PMR and GCA appear to be more common in whites of northern European descent than

in other racial groups. The incidence rate of GCA in whites of northern European descent has been estimated at around 20 to 30/100,000. Reports from other groups including southern Europeans, African Americans, Asians, and Arabs describe a much lower incidence rate at 1 to 11/100,000. Polymyalgia rheumatica is approximately three times more common than GCA, which in turn has been reported as the most common form of vasculitis in the older than 50 years age group and the incidence increases with age until the ninth decade of life. These conditions are exceedingly rare in individuals younger than 50 years. Women have an increased frequency of both PMR and GCA when compared to men (1.7:1 for PMR and 3.5:1 for GCA).

in other racial groups. The incidence rate of GCA in whites of northern European descent has been estimated at around 20 to 30/100,000. Reports from other groups including southern Europeans, African Americans, Asians, and Arabs describe a much lower incidence rate at 1 to 11/100,000. Polymyalgia rheumatica is approximately three times more common than GCA, which in turn has been reported as the most common form of vasculitis in the older than 50 years age group and the incidence increases with age until the ninth decade of life. These conditions are exceedingly rare in individuals younger than 50 years. Women have an increased frequency of both PMR and GCA when compared to men (1.7:1 for PMR and 3.5:1 for GCA).

Figure 15.1 A prominent, tender temporal artery. Reproduced with permission from Gold DH, Weingeist TA. Color Atlas of the Eye in Systemic Disease. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. |

The central histologic feature of GCA is the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate with predominance of CD4+ T cells and macrophages that can extend across the whole elastic artery vessel wall, but usually concentrates around the internal elastic lamina (Fig. 15.2) (1). Destruction of the internal elastic lamina is a pathognomonic feature of GCA. Giant cells can be present, but are an inconsistent feature of the disease, reported in about 50% of biopsy-proven cases. Large numbers of giant cells in the biopsy specimen have been associated with a higher risk of ischemic complications. Although fibrinoid necrosis could be seen in rare cases, its presence is so unusual that it should raise suspicion for alternative diagnoses. No characteristic histopathologic features have been reported for PMR, and the main role of biopsy is workup of suspected accompanying GCA.

Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis, very likely being part of a common pathophysiologic syndrome, share many clinical characteristics. Polymyalgia rheumatica itself is considered a clinical manifestation of GCA. Nevertheless, a majority of patients with PMR never develop other manifestations of GCA and PMR is still widely considered a stand-alone condition. Giant cell arteritis is mostly recognized by its cranial arteritis and musculoskeletal

manifestations. However, other manifestations of the disease can easily go unnoticed, including those secondary to aortitis (limb claudication, aneurysms, Raynaud’s phenomenon) and wasting with cachexia (fever, night sweats, weight loss, anorexia; Table 15.1) (2). It is very important to note that these clinical subsets are not mutually exclusive, and the clinical presentation can have considerable overlap.

manifestations. However, other manifestations of the disease can easily go unnoticed, including those secondary to aortitis (limb claudication, aneurysms, Raynaud’s phenomenon) and wasting with cachexia (fever, night sweats, weight loss, anorexia; Table 15.1) (2). It is very important to note that these clinical subsets are not mutually exclusive, and the clinical presentation can have considerable overlap.

Table 15.1 Clinical Features of Giant Cell Arteritis Syndromesa | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

Examination

Cranial Arteritis

Cranial arteritis is a result of the inflammatory involvement of the extracranial branches of the carotid artery. Headache is the most common manifestation. The specific characteristics of this headache are variable, without a specific type (could be dull, sharp, or throbbing), location (bilateral or unilateral, temporal, occipital, or diffuse), or intensity (from mild to severe). It is usually the persistence of this complaint that brings it to the attention of the clinician. Another feature that should raise a flag is the increased sensitivity of the scalp to tactile stimuli: suddenly the patient has discomfort with routine activities such as wearing glasses, combing their hair, or laying their head on a pillow. The correlation of this on physical examination is temporal tenderness on palpation, with the additional finding of a pulsating, enlarged, or nodular temporal artery in a few cases. Jaw claudication is one of the most specific symptoms of the disease. It is believed to be caused by demand ischemia in the masseter muscles. Nevertheless, the onset of pain can sometimes happen swiftly after the initiation of mastication. Trismus, facial pain, tongue claudication or infarction, scalp necrosis, and carotidynia are additional manifestations of ischemia in this circulatory bed.

The most feared complication of GCA is the vision loss caused by ischemic compromise of the optic nerve and the choroid induced by posterior ciliary

artery occlusion (a branch of the ophthalmic, which is itself a branch of the internal carotid artery). In half of the patients the onset of vision loss is sudden and, in almost all cases, painless. An important proportion of patients can have premonitory symptoms, including blurred vision, transient monocular visual loss (amaurosis fugax), visual hallucinations, and diplopia. Visual loss caused by GCA is very often irreversible, and its premonitory symptoms can be considered a true medical emergency. On fundoscopic examination, disk edema followed by disk pallor is prominent.

artery occlusion (a branch of the ophthalmic, which is itself a branch of the internal carotid artery). In half of the patients the onset of vision loss is sudden and, in almost all cases, painless. An important proportion of patients can have premonitory symptoms, including blurred vision, transient monocular visual loss (amaurosis fugax), visual hallucinations, and diplopia. Visual loss caused by GCA is very often irreversible, and its premonitory symptoms can be considered a true medical emergency. On fundoscopic examination, disk edema followed by disk pallor is prominent.

Central nervous system ischemia in the form of transient ischemic attacks or strokes can occur as a consequence of GCA and, preferentially, affect the posterior circulation. These are believed to be secondary to thromboembolic disease, narrowing or occlusion of the carotid or vertebrobasilar arteries.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

The main clinical characteristic of PMR is pain and stiffness around the muscles of the shoulder and pelvic girdle. Usually the onset is sudden and the shoulder girdle is affected first. Nighttime pain is common, but in the mornings, the symptoms could be so pronounced that the patient has marked difficulty caring for themselves and can end up confined to bed. There is evidence that the proximal painful manifestations of PMR in the shoulder and pelvic girdle are consequence of inflammation of multiple periarticular shoulder and hip bursas. Peripheral joint swelling that can progress to involve the whole hand is commonly described. True peripheral arthritis heralds more resistant disease. Disuse muscle atrophy can develop in long-standing untreated patients.

Wasting and Cachexia

A prominent systemic inflammatory response leading to a presentation with fever, malaise, and weight loss resembling a fever of unknown origin can occur. It is important to emphasize that GCA accounts for about 20% of cases of fever of unknown origin in individuals older than 65 years. Fever is usually low grade, but spikes of up to 39°C or 40°C are not uncommon. Paradoxically, a presentation with these features accompanied with concomitant high levels of inflammatory markers seems to be protective against the development of cranial arteritis, but it is unclear if this is because of an earlier diagnosis with concurrent earlier exposure to glucocorticoid therapy or the predominance of inflammatory factors that may protect against arterial occlusion.

Aortitis and Peripheral Arterial Occlusion

This is by far the most under-recognized manifestation of GCA, but it affects approximately 10% of patients. Many more may be affected subclinically. Peripheral arterial occlusions affect vascular beds in a manner similar to Takayasu’s arteritis, with a preference for the subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries. Giant cell arteritis rarely involves other vessels such as the femoral, coronary, or mesenteric arteries. Presentation includes limb claudication, Raynaud’s phenomenon, decreased pulses, and bruits over the involved vessels. An additional symptom that can be attributed to peripheral arterial involvement, in this case of the respiratory tract, is a persistent dry cough. Patients with peripheral arterial compromise are usually not affected by concomitant cranial arteritis.

Aortitis tends to preferentially affect the thoracic aorta, leading to aneurysm formation, dissection, and aortic incompetence. Common clinical presentations include dyspnea and chest pain (caused by aortic insufficiency, leading to demand coronary ischemia), along with the finding on routine chest radiographs of an enlarged aortic shadow. Sudden death can also occur, usually as a consequence of aortic dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree