Acquired neuropathies in the lower extremities are common, and all nerves in the foot, ankle, and leg are susceptible to injury by entrapment, compression, traction, laceration, or incarceration in scar. Although the term

nerve entrapment can be used to describe any type of localized, acquired peripheral nerve trunk lesion, Kopell and Thompson classically described entrapment neuropathy as “a region of localized injury and inflammation in a peripheral nerve that is caused by mechanical irritation from some impinging anatomical neighbor” (

1). In practice, acquired peripheral neuropathy has many local causes, and clinical signs and symptoms vary according to the extent of neural damage and the specific nerve trunk involved. Although the literature is replete with reviews of nerve entrapment syndromes (

2,

3), much still remains to be learned about the diagnosis and treatment of the wide variety of painful and disabling acquired neuropathies that affect the lower extremities.

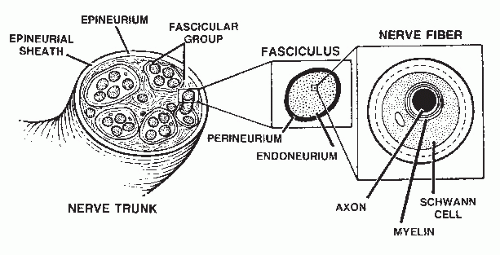

Anatomically speaking, all peripheral nerve trunks are mixed nerves containing sensory, motor, and autonomic fibers. Approximately 50% of the peripheral nerve trunk is made up of connective tissue (

4) (

Fig. 66.1). It is this intraneural connective tissue that, when appropriately stimulated, may proliferate and disrupt the internal continuity of the peripheral nerve trunk. Resultant intraneural fibrosis, alone or in combination with extraneural scarring, can cause symptomatic neuritis. Diagnosis of such a nerve lesion requires a thorough knowledge of both the segmental

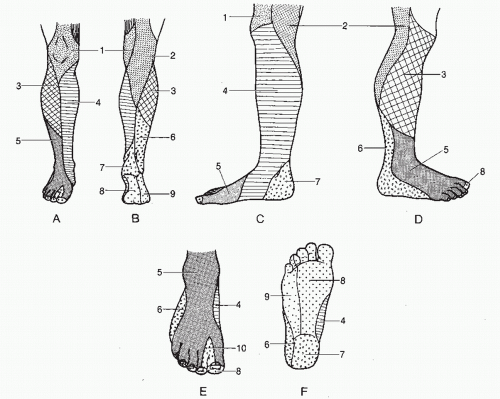

(dermatomal) distribution and the specific cutaneous distribution

(anatomical nerve trunk) supplying the lower extremities (

Fig. 66.2). Furthermore, an understanding of the motor innervation to the lower extremity aids in diagnosis when an abnormal deep tendon reflex or muscle weakness is present (

Table 66.1).

ETIOLOGY OF LOCALIZED ACQUIRED PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY

Localized, acquired peripheral neuropathy may develop after acute gross

trauma or recurrent microtrauma, induced by either endogenous or exogenous sources, when inflammation infiltrates the nerve trunk and surrounding tissues. Usually, the gross continuity of the nerve trunk is maintained, and the nerve may swell proximal to the point of injury or compression (

5). In cases of nerve entrapment, a fusiform or eccentric neuroma in continuity usually develops at the point of impingement. Intraneural fibrosis subsequently proceeds to disrupt the nerve fiber’s myelin sheath and alters impulse conduction. Intraneural fibrosis also inhibits axonal remyelination (

6). If the pathologic influence is allowed to continue, then distal Wallerian degeneration will ensue, and actual myxoid degeneration of intraneural connective tissue with multifocal ganglion formation can develop (

7,

8,

9 and

10). Extraneural scarring and adhesion (perineural fibrosis) aggravate neuritis, and as extraneural fibrosis and resultant compression progress, occlusion of the vasa nervorum ensues. Nerve ischemia leads to further degeneration, decreased impulse conduction, and increased symptoms. The natural history of untreated localized acquired peripheral neuropathy is unpredictable. Symptoms may spontaneously worsen, resolve to a degree, or resolve only to recur on an intermittent basis. When nerve injury has resulted in regional denervation, reinnervation from collateral sprouting of adjacent donor nerves can occur, either spontaneously or by means of surgical neurotization with an adjacent nerve. Various mechanisms cause localized, acquired peripheral neuropathy (

Table 66.2).

Endogenous or spontaneous peripheral nerve entrapments are common. These develop after neighboring anatomical structures have repeatedly microtraumatized an adjacent nerve trunk by means of direct pressure and inhibition of normal peripheral nerve mobility. Neighboring anatomical structures include muscle bellies and fibrous bands, osseous surfaces, and combinations of soft tissue and bone. Congenital anatomical relationships may become a source of nerve compression because of developmental anomalies or abnormal circumstances, such as conditions of overuse that surpass the nerve’s ability to adapt to changes in the local environment. This concept has been referred to as the

stress anatomy of a particular nerve trunk and pertains to conditions of excessive tension or compression on a nerve associated with motion of the extremity (

1).

Other endogenous mechanisms of localized acquired peripheral neuropathy include

neoplastic disorders and other tumors

, such as metastatic infiltration (

11), neurilemmoma (schwannoma) (

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17 and

18), ganglion cyst (

8,

9 and

10,

19), varix, and lipoma, to name a few. Moreover, microvascular dysfunction and subcutaneous atrophy complicating such metabolic diseases as rheumatoid arthritis and other connective tissue disorders (

20), diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease (

19), hyperlipidemia (

21), and hypothyroidism may underlie endogenous forms of peripheral nerve entrapment. Moreover, peripheral nerves in patients with diabetes are more prone to injury than those of persons who do not have diabetes (

22,

23). Still further, the well-accepted

double-crush hypothesis of

peripheral nerve dysfunction proposes that a proximal nerve lesion along an axon, or the presence of concomitant metabolically induced peripheral neuropathy (as observed in diabetes mellitus), predisposes the nerve to injury at a more distal site along its course because of impaired axoplasmic flow (

24,

25,

26,

27 and

28). The double-crush syndrome may also predispose a patient to persistent symptoms despite appropriate nonsurgical or surgical management (

29).

Exogenous causes of localized acquired peripheral neuropathy are also variable. Gross traumatic episodes, including

nerve trunk laceration (

30,

31 and

32), blunt trauma, and compartment syndrome (

33,

34), fracture or dislocation, injection injury (

4,

35,

36,

37,

38 and

39), and excessive traction with resultant intraneural hematoma, have been implicated (

40,

41 and

42). Nerve entrapment also has other iatrogenic causes including tourniquet compression (

43,

44), pressure related to positioning of the anesthetized patient during surgery, bandage or cast pressure (

45), and surgical misadventure (

43,

46,

47). Postoperative scarring secondary to normal wound healing may also create acquired neuropathy, even after proper incision planning, layer dissection, hemostasis, nerve manipulation, and wound closure. Finally, local infection and hematoma causing postinflammatory fibrosis may effect peripheral entrapment neuropathy.