General Considerations

Peter F. M. Choong

Tumor resections about the ankle are uncommon because primary and secondary malignancies infrequently develop in this region. Should they occur, then the two sites that have the greatest impact on ankle function are the distal tibia and the talus. In the nononcologic setting, the greater use of ankle prostheses has witnessed the potential for greater numbers of revision surgery. Advances in technique, biologic reconstructions, prosthetic design, and experience with ankle joint replacement coupled with a better understanding of the indications and contraindications have increased the popularity of limb-sparing surgery for distal tibial and ankle tumors. Whether surgery is for tumor or complex arthroplasty, procedures about the ankle require special care because of the confluence of neurovascular structures anteriorly and medially around the ankle, the relative thinness of the investing skin of the ankle, and the need for the ankle to sustain the entire body weight when standing or moving.

INDICATIONS

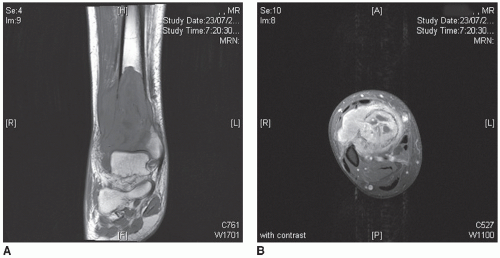

Primary malignancies of the distal tibia are few. Of these, osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma are by far the commonest. Both these tumors distinguish themselves by the soft tissue component, which frequently accompanies the tumor’s development (Fig. 23.1A,B). In the confined area of the ankle, extraosseous extension of the tumor may compromise the ability to undertake limb-sparing surgery. The main reasons are the lack of a robust layer of soft tissue around the ankle to provide the necessary structures to include in a wide margin and the vulnerability of the neurovascular structures that hug the ankle joint. Successful surgical management has a great reliance on chemotherapy or radiotherapy to assist in the containment and reduction of the soft tissue component of both these tumors.

If limb-sparing surgery is possible, then careful dissection would be required to prevent injury to the vital structures and the overlying skin or transgression of the tumor boundaries. In planning a wide resection of

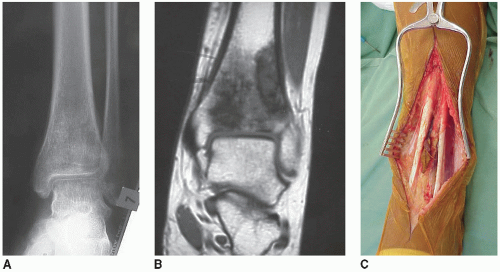

the distal tibia, care must be taken to accurately calculate the amount of residual tibia remaining after tumor resection. This will determine the type of reconstruction possible. For example, short resections lend themselves to almost all varieties of reconstructions including biologic reconstructions (Fig. 23.2A-H), prosthetic reconstructions, and combinations of these (1,2,3,4,5,6). Long resections, however, make prosthetic reconstructions with megaprostheses difficult because of the lack of tibial length to contain the stem of a megaprosthesis. Unlike the femur where long resections of either the proximal or distal femur may be converted to total femoral resections, no device or reconstruction is readily available for extended tibial resections. In this regard, appropriate

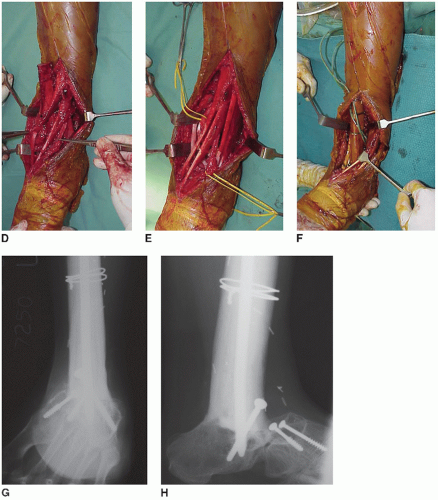

care must be taken to exclude the presence of intramedullary skip lesions. If limb-sparing surgery cannot be undertaken with oncologically sound margins or the potential for postoperative complications outweigh the benefits of this surgery, then below knee amputation should be seriously considered (Fig. 23.3A-C). The function possible with appropriately fitted amputation prostheses, after below knee amputation, is generally excellent.

the distal tibia, care must be taken to accurately calculate the amount of residual tibia remaining after tumor resection. This will determine the type of reconstruction possible. For example, short resections lend themselves to almost all varieties of reconstructions including biologic reconstructions (Fig. 23.2A-H), prosthetic reconstructions, and combinations of these (1,2,3,4,5,6). Long resections, however, make prosthetic reconstructions with megaprostheses difficult because of the lack of tibial length to contain the stem of a megaprosthesis. Unlike the femur where long resections of either the proximal or distal femur may be converted to total femoral resections, no device or reconstruction is readily available for extended tibial resections. In this regard, appropriate

care must be taken to exclude the presence of intramedullary skip lesions. If limb-sparing surgery cannot be undertaken with oncologically sound margins or the potential for postoperative complications outweigh the benefits of this surgery, then below knee amputation should be seriously considered (Fig. 23.3A-C). The function possible with appropriately fitted amputation prostheses, after below knee amputation, is generally excellent.

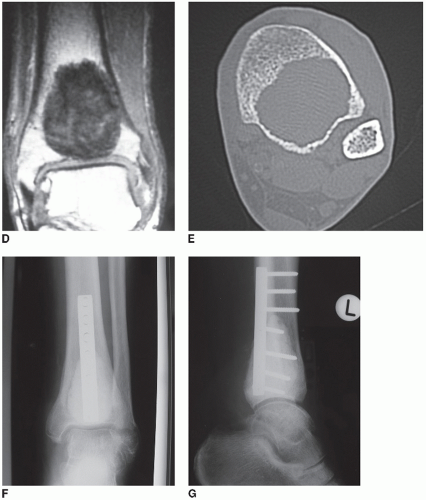

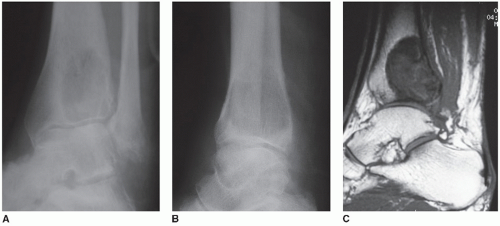

Metastatic carcinoma infrequently involves the distal tibia or tarsal bones. These lesions are either sclerotic, lytic, or a combination of these. Extraosseous extension of tumor may occur but typically is not as prominent as for primary malignancies, thus allowing local surgical treatment such as excisional curettage with maximal preservation of host bone (Fig. 23.4A-G). As with all metastatic diseases, if the diaphysis of the tibia is affected and there is a risk of development of other lesions, then protection of the entire bone with a durable construct should be planned.

FIGURE 23.4 Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) plain radiographs of a melanoma deposit in a distal tibia. T1-weighted sagittal (C) and coronal. |