General Considerations

Peter F. M. Choong

Reconstructions of defects in the bony pelvis are some of the most complex challenges in surgery. The approach to such surgery is heavily influenced by the etiology of the pelvic defect, the anatomy of the pelvis, the reconstructive techniques used, and the acute physiologic disturbance experienced by the patient. The morbidity of pelvic reconstruction is high and pelvic reconstruction should be practiced in a team setting with adequate technical, physical, and expert resources available.

STRATEGIC APPROACH TO PELVIC RECONSTRUCTION

The complexity of pelvic reconstruction mandates a strategic approach to surgery.

A clear understanding of the cause of the pelvic defect is fundamental to its management. For example, recognizing the differences in primary or secondary tumor behavior will determine the approach to resection and the subsequent residual defect. Similarly, an appreciation of the causes of acetabular prosthetic failure will lead to the appropriate choice of reconstruction.

Thorough imaging allowing careful scrutiny of the anatomy is mandatory. Recognizing the extent of the pelvic defect helps to identify what reconstructive technique may be required.

Classification systems that define the potential defect are important for determining the approach and reconstructive options.

Understanding the anatomy of the pelvis allows anticipation of danger zones that may be encountered or avoided.

Careful selection of the surgical approach is important for visualising the region of interest and for achieving adequate access for each step of the procedure. This will be determined by the location of the tumor or, in the case of acetabular revision, the nature of prosthetic failure. The surgical approach will determine how the patient is positioned and draped.

Pelvic surgery is frequently prolonged and complicated by heavy blood loss. Managing the physiologic upset during the procedure is an important consideration and requires a close working relationship with the anesthetic team.

ETIOLOGY OF PELVIC DEFECTS

The two commonest causes for pelvic defects include resection of pelvic tumors and periacetabular prosthetic complications. While the etiologies and implications of these two problems may differ substantially, the same methodical and meticulous approach must be employed in executing the surgical plan. In some cases, very similar surgical techniques are required to address the bone defect.

Primary Tumors

The pelvis is a common site (10%) for the development of primary tumors. The commonest primary pelvic tumors include chondrosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma (1). Primary malignancies may be treated with curative intent. If systemic spread has occurred, then the prime aim of pelvic surgery is the local control of disease. The principle of tumor resection is to achieve a wide surgical margin for clearance, which is defined as at least 2 cm of clear bone in the line of the bone and a cuff of normal tissue, which is a named anatomic layer such as muscle, or fascia that is parallel to the cortex of the bone (2). Surgery may be combined with neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The extent of the wide margins will determine the amount of bone loss and the subsequent reconstruction. Furthermore, inclusion of soft tissue as part of the margin may add to the complexity by extending the dead space and compromising safe wound closure.

Secondary Tumors

Bone metastases occur in almost 60% of carcinomas (3). The pelvis is one of the most common sites for metastases with breast, lung, prostate, kidney, and thyroid carcinoma being the primary sources (3). With the exception of renal carcinoma, most metastatic bone tumors are permeative, poorly circumscribed, sclerotic, lytic or mixed, and not associated with a large soft tissue component. In contrast, renal carcinoma metastases are characterized by large cannon-ball-like lesions which are profoundly lytic and associated with a large soft tissue component and hypervascularity.

Unlike primary bone malignancies which are solitary and are treatable by wide surgical margins, metastatic disease is conventionally treated with bone-conserving procedures such as curettage or the removal of only macroscopically affected tissue. This is because true solitary metastases are uncommon with the high likelihood that there are micrometastatic lesions within the same bone at the time of diagnosis. In light of this, bone metastasis should be regarded as a locally progressive disease with the expectation that despite surgical intervention, recurrence of disease will occur. Periprosthetic recurrence of tumor may rapidly lead to failure of the device; therefore, reconstructions should aim for maximum durability in the setting of ongoing bone loss and a shortened patient survival. For example, the entire length of tubular and flat bones should be spanned when considering internal fixation to avoid fracture through unprotected bone distal to a fixation device. The judicious use of cement as filler or to supplement fixation should be encouraged rather than relying solely on individual screws which are easily loosened by tumor progression. Cemented prosthetic fixation is preferred when considering hip arthroplasty for the same reason.

Primary pelvic tumors are characterized by late presentation. The capacious volume of the pelvis or the abundant fat and muscle around the pelvic girdle frequently masks the presence and development of pelvic tumors until they have reached enormous sizes. Soft tissue sarcomas are frequently painless as compared to bone malignancies which often cause painful symptoms. These later symptoms, however, are often vague and can be misinterpreted as musculoskeletal injury or as pain referred from the lumbar spine. Symptoms from intrapelvic soft tissue tumors are often from their compressive effect on adjacent viscera.

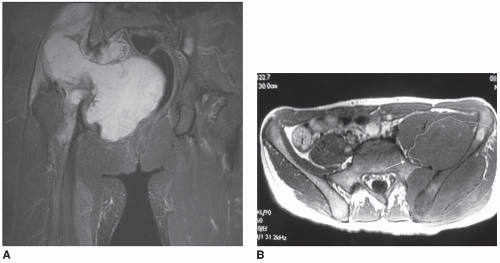

The frequently large tumor size can make dissection difficult by distorting normal anatomy, and displacing viscera and major neurovascular structures from their known course (Fig. 1.1A). Large primary pelvic tumors which necessitate wide resection margins may be complicated by the need to protect vital neurovascular structures that lie within the resection margin. For example, the lumbosacral nerve trunk, which passes downwards and laterally in front of the sacral alar toward the sciatic notch, can be compressed by tumors arising from the sacrum and sacroiliac joint or may be vulnerable to injury when the resection margin passes through the sacral alar for a large iliac sarcoma (Fig. 1.1B). Tumors that overhang the sciatic notch may obscure the passage of the sciatic nerve and the branches of the internal iliac vessels as they traverse the notch, making them vulnerable to injury. Tumors of the anterior pelvis may compress the bladder, or obstruct the superficial femoral artery and vein or the femoral nerve as these structures course across the superior pubic ramus. Structures which are held to the pelvis by fascia such as the lumbosacral nerve trunk or the femoral vessels and nerve are particularly vulnerable to tumor compression or iatrogenic trauma.

Periacetabular Prosthetic Complications

Periacetabular prosthetic complications requiring revision represent some of the most challenging surgeries in orthopaedics (Fig. 1.2). With an increase in the numbers of joint replacements worldwide and the legacy of early generation components and implantation techniques, the requirement for complex acetabular revisions is certain to rise. The same meticulous approach to managing pelvic tumors may be applied to acetabular prosthetic complications.

Reconstructing acetabular defects after removal of acetabular prostheses is influenced by the quality of the residual bone, which is often poor. Frequently, the defects are cavitatory or segmental and are caused by osteolysis, the abrasion of a mobile acetabular component, and the damage caused by removal of the implant (4,5,6). What bone remains is commonly sclerotic with a paucity of good trabecular bone for interdigitation of cement or a reliable surface on which to support a cementless prosthesis. Central acetabular protrusion in bone softening conditions such as osteoporosis, osteomalacia, chronic steroid use, or Paget disease add to the difficulty that arthroplasty surgeons face. If acetabular loosening is accompanied by sepsis, then additional soft tissue debridement is required and surgery to reconstruct the pelvis may require a staged approach. What is sometimes also observed is the presence of significant and occasionally multiple, large serpiginous evaginations of the hip capsule containing darkly discolored pultaceous material. The latter is the by-product of metallic, polyethylene, and/or cement interface wear. The impact of this residue on newly revised bearing surfaces is unclear, but its total removal with excision of the granulomatous lining of the capsule should be undertaken. Backside acetabular wear is becoming a well-recognized cause of damage to the periacetabular bone and large

cystic cavities may develop. Early modular implants gave rise to the unexpected phenomenon of polyethylene wear (7,8,9,10), which is now being addressed by better materials and design (8,11,12,13). Large cysts need to be appropriately curetted and grafted as part of the operative procedure.

cystic cavities may develop. Early modular implants gave rise to the unexpected phenomenon of polyethylene wear (7,8,9,10), which is now being addressed by better materials and design (8,11,12,13). Large cysts need to be appropriately curetted and grafted as part of the operative procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree