Chapter 38 Gastroenterology

Epidemiology and Social Impact of Gastrointestinal Disease

Approach to the Patient with Gastrointestinal Complaints

Psychosocial Factors of Gastrointestinal Disease

Locke’s review in Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease (8th edition) provides an excellent framework of the biopsychosocial approach to the patient with GI complaints. In caring for patients with both acute and chronic GI disorders, family physicians should obtain a patient-centered, nondirected history, using open-ended questions that enable patients to tell the history in their words. Medical and social histories should be integrated so that symptomatic complaints are described in the context of the psychosocial events surrounding the presenting illness, including the setting of symptom onset and exacerbation. Throughout the encounter, the provider’s questions should communicate a sincere willingness to address both biologic and psychologic aspects of the illness. Evaluation and treatment of GI symptoms depend on a strong physician-patient therapeutic relationship, allowing the family physician to elicit, evaluate, and communicate the role of potential psychosocial factors in the disease state. Patient reassurance, acknowledgment of patient adaptations to chronic illness, reinforcement of healthy behaviors, and the consideration of psychopharmacologic medication are paramount (Locke, 2006).

The Abdominal Examination

For descriptive purposes of location, the abdomen has been divided into four quadrants, constructed by an imaginary vertical line from the tip of the xyphoid process to the pubic symphysis and an imaginary horizontal line bridging the anterior superior iliac crests, referred to as the right upper (RUQ), right lower (RLQ), left upper (LUQ), and left lower (LLQ) quadrants (Bickley, 2008). The abdomen can be further divided into the epigastric, umbilical, hypogastric or suprapubic, and right and left flank regions. Knowledge of anatomic structures that lie in each of these quadrants and regions is imperative for the clinician to form an accurate differential diagnosis in relation to a patient’s presenting symptoms (Box 38-1).

Box 38-1 Differential Diagnosis for Abdominal Pain Based on Location

Modified from Differential diagnosis. In Ferri FF. Ferri’s Clinical Advisor 2010. Philadelphia, Saunders-Elsevier, 2010.

Left lower quadrant

Right lower quadrant

Diffuse

Common Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disorders

Diarrhea and Dehydration

Symptoms of volume depletion (increased thirst, tachycardia, orthostasis, decreased urine output, lethargy, decreased skin turgor, decreased tear production)

Symptoms of volume depletion (increased thirst, tachycardia, orthostasis, decreased urine output, lethargy, decreased skin turgor, decreased tear production) Associated symptoms and their frequency and intensity (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, cramps, headache, myalgias, altered sensorium)

Associated symptoms and their frequency and intensity (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, cramps, headache, myalgias, altered sensorium) Consumption of unsafe foods (e.g., raw meats, eggs, or shellfish; unpasteurized milk or juices) or swimming in or drinking untreated fresh surface water from a lake or stream

Consumption of unsafe foods (e.g., raw meats, eggs, or shellfish; unpasteurized milk or juices) or swimming in or drinking untreated fresh surface water from a lake or stream Underlying medical conditions predisposing to infectious diarrhea (AIDS, immunosuppressive medications, prior gastrectomy, extremes of age)

Underlying medical conditions predisposing to infectious diarrhea (AIDS, immunosuppressive medications, prior gastrectomy, extremes of age)In the majority of patients with acute gastroenteritis, the “gold standard” stool cultures and ova and parasite testing are seldom required, because the disease is most often viral in etiology and self-limited. In more severe cases with dehydration, metabolic derangement, longer duration, bloody stools (dysentery) and mucus in the stool, or known or suspected transmission of a pathogen, these tests are often required to identify the pathogen and to direct appropriate antimicrobial therapy (Table 38-1). Viral cultures are rarely performed and are unnecessary, except in rare cases and immunocompromised patients. Although fecal leukocytes and lactoferrin often suggest an inflammatory etiology of diarrhea, there is no consensus regarding the routine use of these tests in the initial testing of patients with either community-acquired or nosocomial diarrhea. Hospitalized patients with diarrhea, especially those with abdominal pain, should be tested for Clostridium difficile toxin (Guerrant et al., 2001). Oral metronidazole and oral vancomycin have been shown to be equally effective in the treatment of C. difficile–associated diarrhea (CDAD). Vancomycin is significantly more expensive and may select for colonization with vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and thus metronidazole should be recommended as first-line therapy.

Table 38-1 Common Pathogens and Recommended Therapy for Acute Diarrhea

| Pathogen | Therapy (Adult Doses) |

|---|---|

| Campylobacter jejuni | Azithromycin, 500 mg qd for 3 days or Ciprofloxacin,∗ 500 mg bid for 7 days |

| Clostridium difficile | Metronidazole, 500 mg tid, or 250 mg qid, for 10 14 days or Vancomycin, 125 mg qid for 10-14 days |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Metronidazole, 500-750 mg tid for 10 days or Tinidazole, 2 g qd for 3 days followed by Paromomycin, 500 mg orally tid for 7 days or Iodoquinol, 650 mg tid for 20 days |

| Escherichia coli 0157:H7 | No treatment with antimicrobials or antimotility drugs |

| E. coli (toxigenic) | Azithromycin, 1 g in 1 dose or Rifaximin, 200 mg tid for 3 days or Levofloxacin,∗ 500 mg for 1 dose |

| Giardia lamblia | Tinidazole, 2 g in 1 dose or Nitazoxanide, 500 mg bid for 3 days or Metronidazole, 500-750 mg tid for 5 days |

| Salmonella spp. (non-typhi)† | Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg bid for 5-7 days or Azithromycin, 1 g for 1 day, then 500 mg qd for 6 days |

| Shigella spp. | Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg bid for 5-7 days or Levofloxacin, 500 mg qd for 3 days or TMP-SMX-DS, 1 tablet bid for 3 days or Azithromycin, 500 mg for 1 dose, then 250 mg qd for 4 days |

| Staphylococcus aureus (food poisoning) | No treatment with antimicrobials or antimotility drugs |

| Vibrio cholerae | Ciprofloxacin, 1 g in 1 dose, plus aggressive fluid hydration |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | No treatment with antimicrobials or antimotility drugs |

| Yersinia enterocolitica |

TMP-SMX, Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; DS, double strength; IV, intravenously; qd, once daily; bid, twice daily; tid, three times daily; qid, four times daily.

∗ Avoid fluoroquinolones in pediatric patients and pregnant women.

† Antimicrobial therapy not indicated in asymptomatic patients or those with mild illness. Treatment advised in patients less than 1 year old or greater than 50 years old, if immunocompromised, or if patient has a vascular graft or prosthetic joints.

Modified from Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, Eliopoulos GM, et al. The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy, 39th ed. Vermont, Antimicrobial Therapy, 2009.

KEY TREATMENT

Appendicitis

A diagnosis of appendicitis should be considered in any pediatric patient presenting with acute abdominal pain. Acute appendicitis often presents with a constellation of signs and symptoms, including fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, tenesmus, migratory RLQ abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness and guarding, and signs of peritoneal irritation. Classically, hours after onset, the pain migrates to McBurney’s point, defined as the point two-thirds the distance from the umbilicus along a straight line toward the anterosuperior iliac spine of the pelvis. Rovsing’s sign (referred tenderness from LLQ to RLQ during palpation), psoas sign (pain elicited by extending hip posteriorly with patient lying prone), and obturator sign (pain elicited by abducting right hip with patient lying supine) are often conducted but are of little diagnostic value. No sign or combination of signs has accurately predicted acute appendicitis in children (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital [CCH], 2002).

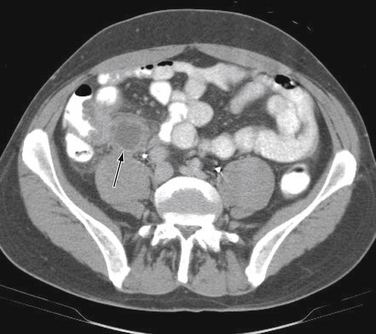

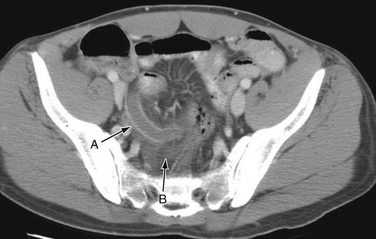

Diagnostic imaging is not routinely recommended in patients with a high or a low probability of appendicitis, because it can alter management strategies and has not proved cost-effective; imaging is most helpful when the clinical assessment is equivocal. Controversy exists over the superiority of ultrasound versus computed tomography (CT) in accurately diagnosing appendicitis, and both tests have a positive predictive value approaching 100%. Although ultrasound may be advantageous in thin patients, CT is preferred in the evaluation of a more obese child (Halter et al., 2004). Typical radiographic findings in the evaluation of acute appendicitis include appendicoliths (Fig. 38-1), dilation of the appendix with adjacent hazy fat (Fig. 38-2), and periappendiceal abscesses (Fig. 38-3). If the abdominal CT does not show evidence of acute appendicitis, the patient may either be admitted for observation or discharged at the discretion of the examiner and parents, with instructions for follow-up if symptoms worsen. Expert opinion states that if there is high suspicion of appendicitis on the basis of history, physical examination, and laboratory studies, the patient should go directly to the operating room for an exploratory laparotomy to evaluate the appendix, without an imaging study.

Figure 38-1 Appendicolith.

(Courtesy Dr. Perry Pernicano, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor.)

Figure 38-2 Appendicitis. Dilated thickened appendix (A), with adjacent hazy fat (B).

(Courtesy Dr. Perry Pernicano.)

Common Adult Gastrointestinal Disorders

Esophagus

Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

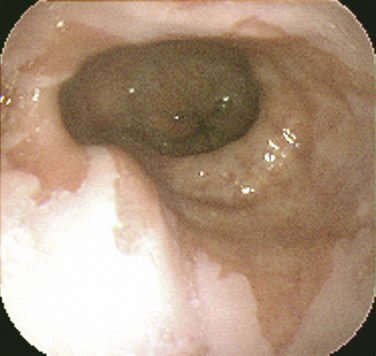

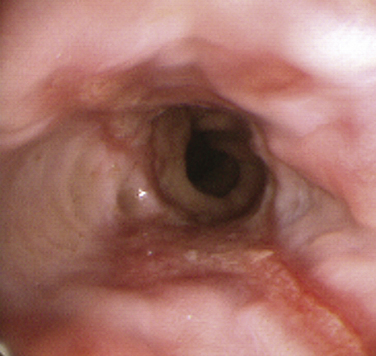

Barrett’s esophagus is a premalignant condition related to chronic GERD. The hallmark is a change in the mucosal lining of the distal esophagus from the normal squamous epithelium to columnar-appearing mucosa resembling that of the stomach and small intestines, referred to as intestinal metaplasia (Fig. 38-4). The estimated risk of progression to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus with Barrett’s esophagus is approximately 0.5% per year, whereas without Barrett’s esophagus the risk is 0.07%, prompting development of clinical practice guidelines for surveillance endoscopy. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has had the fastest-rising incidence of any cancer in the United States and Western Europe over the last two decades. Family and other primary care physicians who see the vast majority of patients with GERD in its nonerosive and more complicated forms are charged with the task of suspecting and appropriately referring patients with Barrett’s esophagus for EGD. Although risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma are not evidence-based, there is suggestive evidence that male gender, white race, older age, dysplasia, smoking, and obesity place patients at a higher risk (Sampliner, 2002).

Stomach and Duodenum

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and a leading cause of dyspepsia (Box 38-2), with a cumulative lifetime prevalence of 8% to 14% (Fig. 38-5). Although up to 70% of patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers are 25 to 64 years old, the peak prevalence of complicated ulcer disease requiring hospitalization is age 65 to 74 (Saad and Scheiman, 2004).

Box 38-2 Causes of Dyspepsia

Modified from Saad R, Scheiman JM. Diagnosis and management of peptic ulcer disease. Clin Fam Pract 2004;6:569-587.GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

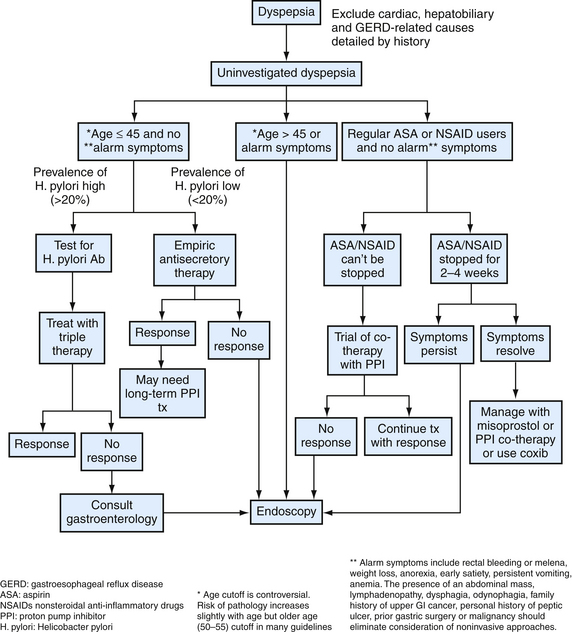

Numerous options exist for the management of uninvestigated dyspepsia in primary care (Fig. 38-6). Given the high cost and often limited access to endoscopy testing, not all patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia should undergo an invasive investigation of their symptoms. The presence of “alarm symptoms” for PUD raises concern for a gastric malignancy. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA, 2005) endorses prompt endoscopic evaluation in any patient over age 45 with new-onset dyspepsia.

Figure 38-6 Evaluation of uninvestigated dyspepsia.

(Modified from Saad R, Scheiman JM. Diagnosis and management of peptic ulcer disease. Clin Fam Pract 2004;6:569-587.)

The evidence-based standard of care dictates that patients with dyspepsia and no alarm symptoms should be tested for H. pylori infection and then given eradication therapy if positive, (“test and treat”) (Chey and Wong, 2007). H. pylori–positive or H. pylori–negative patients who do not undergo endoscopy initially should do so if their symptoms persist. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with ulcers in the community; as in some geographic areas, prevalence may be too low to make this approach effective.

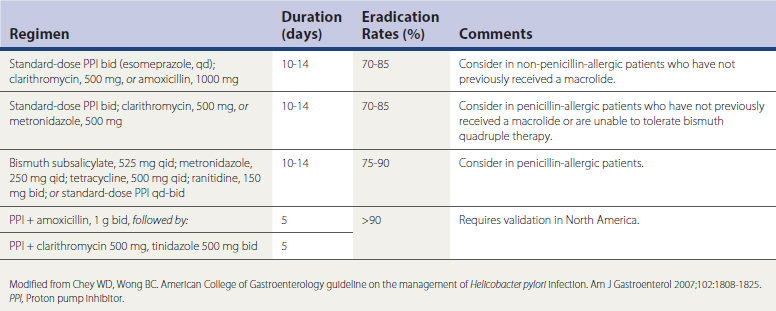

Several medication regimens have been developed for the treatment of confirmed H. pylori infection, based on data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews (Table 38-2). The best evidence-based recommendation for H. pylori eradication is for 14-day triple therapy with the use of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin, and either amoxicillin or metronidazole, yielding eradication rates from 70% to 85%. The most common salvage regimen in patients with persistent H. pylori is bismuth quadruple therapy. Recent data suggest that 10-day therapy with a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin is more effective and better tolerated than bismuth quadruple therapy for persistent H. pylori infection (Chey and Wong, 2007).

Another major etiology of PUD is the increasing and widespread use of both NSAIDs and aspirin. The use and overuse of these medications is the most common cause of PUD in H. pylori–negative patients, and up to 60% of unexplained cases of PUD are attributed to unrecognized NSAID use. In a meta-analysis of observational studies of GI bleeding risk from various NSAIDs, a fourfold increased risk associated with NSAID-use persisted throughout therapy and fell to baseline within 2 months of discontinuation of the drug (Hernandez-Diaz and Rodriguez, 2000). Although both H. pylori and aspirin/NSAIDs are involved in the overwhelming majority of PUD cases, other factors contribute to the remaining 1% to 5% (Box 38-3).

Box 38-3 Etiology of Peptic Ulcer Disease

From Heidelbaugh JJ. Peptic ulcer disease. In Rakel RE (ed). Essential Family Medicine, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Saunders-Elsevier, 2006.

Independent risk factors that augment the impact of H. pylori and NSAID-related PUD risk and may promote ulcer complications include advancing age; history of PUD or complicated ulcer disease with perforation, penetration, or gastric outlet obstruction; use of multiple NSAIDs (including concomitant use of low-dose aspirin and an NSAID); and concurrent warfarin or corticosteroid use. Evidence suggests that smoking may increase the risk of PUD and ulcer complications by impairing gastric mucosal healing. Alcohol use may increase the risk of ulcer complications in NSAID users, but its overall effect in those patients without concomitant liver disease has not been clearly defined. Currently, no solid evidence implicates dietary factors in the development of PUD.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

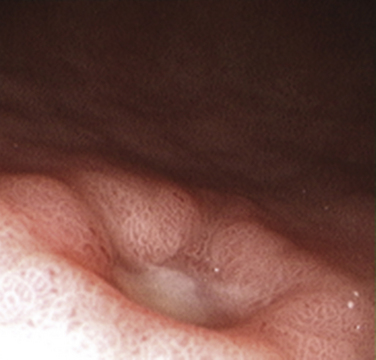

Most patients with GERD evaluated in primary care practices have nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), although some will progress to erosive esophagitis (Fig. 38-7), and even fewer to more severe disease resulting in esophageal strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus (DeVault and Castell, 2005). Patients with NERD are prone to develop atypical or extraesophageal manifestations of disease (Box 38-4). Because of a small risk of disease progression, however, they generally do not require long-term surveillance despite persistent reflux symptoms. Symptom relapse rates in patients with NERD are similar to those in patients with erosive esophagitis, and although many will require continuous pharmacotherapy to control their symptoms, almost all continue to exhibit no definable erosive esophagitis on upper endoscopy (Fass, 2002).

Box 38-4 Atypical or Extraesophageal Manifestations of GERD

Modified from Heidelbaugh JJ, Nostrant TT. Medical and surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Fam Pract 2004;6:547-568.

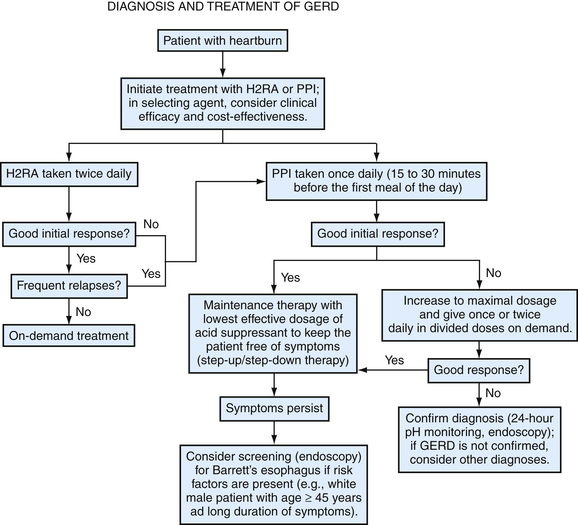

The goals of GERD treatment are to relieve symptoms, heal erosive esophagitis if present, manage and prevent complications, and avoid recurrence and progression of disease using acid-suppressive medications. Initial empiric pharmacotherapy should consist of either an H2RA or a PPI, without the need for immediate diagnostic testing in the vast majority of cases. Expert opinion supports either step-up or step-down therapy for the initial treatment of patients with GERD (Inadomi, 2002). In patients who incompletely respond to H2RAs, PPIs taken once daily 30 minutes before the first meal of the day are preferred over continuing H2RA therapy because of greater efficacy and faster symptom control with PPIs. An inadequate response to a 4- or 8-week trial of standard-dose PPI may indicate the need for longer treatment, more severe disease, or an incorrect diagnosis (Fig. 38-8). Additional benefit may be obtained by extending treatment for another 4 to 8 weeks with the same or a double dose of PPI (Medical Advisory Panel, 2003).

Figure 38-8 Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

(Modified from Heidelbaugh JJ, Nostrant TT. Medical and surgical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Fam Pract 2004;6:547-568.)

Diagnostic testing is recommended in patients with GERD who have an inadequate response to PPI therapy, need continuous chronic therapy to control frequent GERD symptoms, have chronic symptoms (>5 years) and are at risk for Barrett’s esophagus, have atypical or extraesophageal manifestations suggesting complicated disease, or have alarm symptoms suggesting cancer (Box 38-5).