Ganglion Excision

Michael J. Botte

Lorenzo L. Pacelli

Michael A. Thompson

Indications and Contraindications

Carpal ganglion excision is indicated when (a) the cystic mass is painful, interferes with function, or causes local nerve compression; or (b) histologic tissue is desired for definitive diagnosis of a mass lesion. Excision is generally recommended for the symptomatic lesion when nonoperative methods have been inadequate. Nonoperative methods include rest, activity modification, anti-inflammatory medication, splinting, aspiration, cyst wall needle puncture, steroid or hyaluronidase injection, and patient reassurance (1,2,3,4,5,6). Symptomatic ganglia that warrant excision include pain, tenderness, loss of wrist motion, weakness, numbness, or paresthesias (1,2,6,7,8,9). Lesions can encroach on neurovascular structures and result in carpal tunnel syndrome, ulnar tunnel syndrome, neuropathy of the superficial branch of the radial nerve, or radial or ulnar artery compression. These ganglia should be excised (10,11), including those encountered incidentally during decompression of the carpal tunnel or Guyon’s canal. Small, occult ganglia encountered incidentally during operative exploration in the patient with chronic wrist pain also warrant excision (6,12). Although rare, ganglia that cause unusual symptoms (e.g., tendon triggering or loss of wrist motion) should also be excised.

Relative contraindications to excision include patient’s poor medical status or an allergy history that precludes general, regional, or local anesthesia; the presence of infection, open wounds, or abrasions; or chronically contaminated inflammatory skin conditions (e.g., severe psoriasis).

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning includes medical history, physical examination, roentgenograms, and commonly, diagnostic or therapeutic aspiration. Transillumination may give additional information if the diagnosis is in question. Studies, such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), provide additional information as to diagnosis and can outline the extent and origin of the lesion (12,13,14,15). Preoperatively, inform the patient of the possible need for hand therapy in the postoperative period to regain motion and strength.

Medical History

Salient medical history information that aids diagnosis includes the circumstances of the mass and its origin (spontaneous or following trauma); length of time the mass has been present; changes in size, shape, or consistency; and the nature, degree, and fluctuations of related symptoms. Information relevant to treatment decisions includes the degree of discomfort or dysfunction (e.g., night pain and pain that interferes with work or with activities of daily living) or any related symptoms of nerve or vascular compression or carpal instability. A history of previous treatment, such as aspiration or excision, is important.

Because ganglia are somewhat unique in their ability to change in size and in associated symptoms, such characteristics are key aspects in diagnosing the lesion. Ganglia often enlarge or become more symptomatic following activity. The lesions can regress in size or resolve, either spontaneously

or following direct and sudden applied pressure or trauma. Other lesions, neoplasms, and infections rarely change or regress as readily.

or following direct and sudden applied pressure or trauma. Other lesions, neoplasms, and infections rarely change or regress as readily.

A history of a previous puncture wound in the presence of a wrist mass that resembles a ganglion raises additional diagnostic considerations of an inclusion cyst, foreign body granuloma, or infectious granuloma. A history of inflammatory arthritis or crystalline arthropathy is significant because synovitis, tenosynovitis, rheumatoid nodules, gouty tophi, or joint effusions can resemble ganglia.

Previous trauma may be relevant if the patient has concomitant carpal instability or arthritis that may be related to the cause of the ganglion. These other problems may warrant treatment as well.

Patient history concerning occupation and handedness aids little in diagnosis of the lesion, because correlation of these factors with the presence of ganglia has not been demonstrated (1,2,7,8). Ganglia have been shown to be slightly more prevalent in women, occurring most often in the second, third, and fourth decades of life (1,2,7,9,16).

Footnote

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Physical Examination

Examine the mass as to location, size, extension, and presence of adjacent satellite lesions or loculations. Palpate for tenderness, consistency, fluctuance, and adherence to other structures. Digital compression or ballottement of the mass may help reveal the lesion’s extent and the direction of the pedicle.

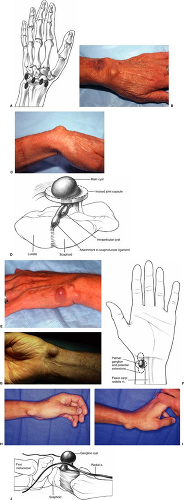

Ganglia on the dorsum of the wrist (70% of all hand and wrist ganglia) (1,2,7,8,16) usually are located mid-dorsally, originating most often from the scapholunate joint (Fig. 44-1A-D). Palmar flexion of the wrist accentuates the boundaries of the dorsal ganglion and may reveal an occult ganglion. Palpate multiloculated lesions to assess extent and origin of the pedicle (Fig. 44-1E). Palpation helps distinguish ganglia from extensor tenosynovitis, dorsal carpal synovitis, carpal effusion, rheumatoid nodules, gouty tophi, or a carpal boss.

Perform preoperative functional hand and wrist evaluations, including active and passive motion, manual muscle testing, grip and pinch strength, and sensibility evaluation with two-point discrimination and monofilament testing. Perform standard vascular examination (noting skin temperature, color, capillary refill, and turgor), palpation of pulses, and Allen’s testing (to demonstrate possible arterial compromise, especially with palmar ganglia located adjacent to the radial artery). Examine for carpal instability with palpation for wrist clicks during active or passive motion and perform the scaphoid shift test on the affected and unaffected sides to determine scaphoid instability (17). Examine digital and wrist motion for mechanical block or tendon triggering, which can occur if ganglia are near the extensor retinaculum or within the carpal canal. Gently percuss the lesion to elicit Tinel’s sign, which indicates peripheral nerve encroachment.

Ganglia on the palmar aspect of the wrist are usually located near the radial artery or flexor carpi radialis tendon, and originate from the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid, radiocarpal, or trapeziometacarpal joint (Fig. 44-1F-J) (11,16,18). Dorsiflexion of the wrist may accentuate the boundaries of a small or occult palmar ganglion (Fig. 44-1I). Obtain a functional examination as described above, including assessment of the relative location and function of the radial artery, flexor carpi radialis tendon, brachioradialis tendon, and palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. Test patency of the radial artery with palpation, Allen’s testing, and, if needed, Doppler evaluation.

Palpate the radial artery, with and without manual occlusion of the ulnar artery, to eliminate retrograde pulsation. Evaluate sensibility on the dorsoradial aspect of the hand and the base of the thenar eminence to reveal compression of the superficial branches of the radial nerve and of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, respectively. Ganglia on the ulnar side of the wrist warrant similar evaluation of ulnar nerve and artery function.

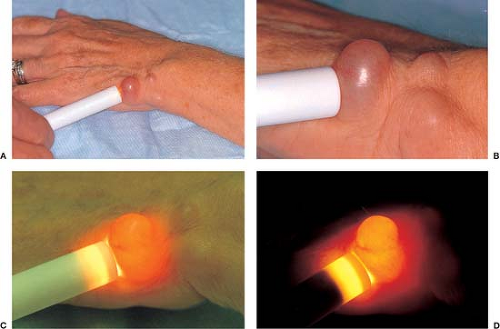

Transillumination

Place a small light against the lesion to transilluminate it. The passage of light through a cystic lesion confirms the diagnosis (Fig. 44-2) and can establish the extent of the boundaries of the lesion. Superficial lesions that do not transilluminate raise the suspicion of solid masses (e.g., a carpal boss, rheumatoid nodule, gouty tophus, or a neoplasm such as a benign fibrous histiocytoma or epithelioid sarcoma).

Roentgenograms and Related Imaging Studies

Standard roentgenograms may show a soft-tissue shadow that further documents the presence and location of the lesion. Roentgenograms may also demonstrate abnormalities associated with, or related to, the development of the ganglion, including arthritis or carpal instability.

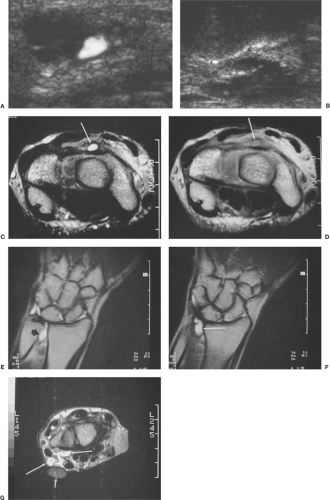

The diagnosis may not be clear in the case of a thick-walled, firm, deeply seated, or small-sized lesion (6,15). Additional helpful diagnostic tests are ultrasound and MRI (Fig. 44-3) (12,13,14,15). Ultrasound determines the cystic nature of a lesion and can help in the assessment of the proximity and the patency of the radial artery to a palmar carpal ganglion (Fig. 44-3A,B). MRI is helpful in establishing the diagnosis in deeply seated or occult ganglions, such as those within the carpal canal or within Guyon’s canal (Fig. 44-3C–G). Both ultrasound and MRI are effective diagnostic methods

if an occult ganglion is suspected, but ultrasound costs less and has fewer contraindications. Ultrasound thus is more suitable for establishing the diagnosis of an occult ganglion when clinical findings are inconclusive (13).

if an occult ganglion is suspected, but ultrasound costs less and has fewer contraindications. Ultrasound thus is more suitable for establishing the diagnosis of an occult ganglion when clinical findings are inconclusive (13).

Although arthrograms of the wrist have demonstrated the one-way valve mechanism and connection of the pedicle to the main cyst, the routine use of arthrograms is not warranted (8,19).

Similarly, arteriograms can assess radial artery patency with adjacent palmar ganglia and have been used to diagnose ganglion-related thromboses. Routine use of arteriograms for palmar ganglia is not indicated, however, because less-invasive, accurate techniques, such as careful palpation, Allen’s testing, Doppler evaluation, and ultrasound, are available.

Similarly, arteriograms can assess radial artery patency with adjacent palmar ganglia and have been used to diagnose ganglion-related thromboses. Routine use of arteriograms for palmar ganglia is not indicated, however, because less-invasive, accurate techniques, such as careful palpation, Allen’s testing, Doppler evaluation, and ultrasound, are available.

The differential diagnosis of the carpal ganglion includes inclusion cysts, inflammatory (rheumatoid) or infectious (tuberculous) synovitis, tenosynovitis, rheumatoid nodules, and gouty tophi. Other conditions that must be considered include foreign body granulomas, giant cell tumors of tendon sheath, lipomas, fibromas, neurilemomas, neurofibromas, carpal bosses, osteochondromas, and, less commonly, lymphangiomas, aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, leiomyomas, aberrant muscle bellies, or chronic abscesses.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspiration

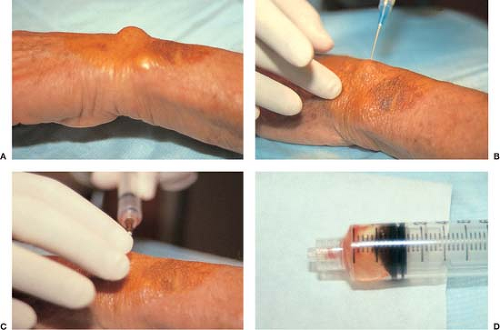

Although aspiration was established as a method of treatment, it is also useful as a diagnostic procedure (Fig. 44-4). Under sterile conditions, anesthetize the skin with 1% lidocaine without epinephrine.

Use a large-bore needle to aspirate the lesion. Flex the wrist during dorsal ganglion aspiration to accentuate and immobilize the ganglion. Mucinous material is usually diagnostic for a ganglion.

Use a large-bore needle to aspirate the lesion. Flex the wrist during dorsal ganglion aspiration to accentuate and immobilize the ganglion. Mucinous material is usually diagnostic for a ganglion.

If aspiration is performed for treatment as well, place multiple punctures in the cyst wall using digital palpation to direct the needle and decompress the mass. Take care during aspiration of palmar carpal ganglia to avoid injury to the radial or ulnar arteries, and during aspiration of dorsoradial ganglia to avoid injury to the radial artery. Following aspiration, immobilize the carpus with the wrist in 10 degrees extension; immobilization should last 3 weeks (5).

From a therapeutic standpoint, aspiration, cyst wall puncture, and injection of a steroid solution have been shown to be an effective method of treatment, especially for the dorsal ganglion (1,2,3,8,10). The additional use of hyaluronidase as a potential adjuvant to aspiration has recently been investigated and results appear promising (4,20,21).

Because of a higher recurrence rate found following aspiration of palmar carpal ganglia, excision instead of aspiration has been suggested as the primary definitive treatment of these ganglia (18).

Patient Discussion and Therapy Planning

When loss of function is present preoperatively, obtain functional evaluation and consultation from a hand therapist before surgery.

Inform the patient before surgery of the benefit of postoperative hand therapy; indicate that such therapy may be needed to regain strength and motion (especially palmar flexion motion following excision of a dorsal carpal ganglion). Such a preoperative discussion alleviates many patient concerns, especially if prolonged therapy is later required. It is common for workers to require several weeks of rehabilitation before they return to heavy or repetitive work (1,2,7); therefore, it is necessary to inform patients of the potential length of the recovery period.

When a palmar ganglion is present, discuss and obtain preoperative surgical consent for carpal tunnel release, because the pedicle may originate from within the carpal tunnel and require transection of the transverse carpal ligament for adequate exposure. Rehabilitation may be prolonged if carpal tunnel release is required.

Operative Technique

Operative excision remains the treatment of choice for symptomatic dorsal or palmar ganglia not responsive to conservative management, or when tissue is desired for diagnosis (Fig. 44-5).

Arthroscopic excision for the carpal ganglion has also recently been described, more commonly addressing the dorsal ganglia (22,23,24,25,26,27). Recent reports support the technique as a reasonable alternative to open resection, (9,22,24,28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree